Tougher than They Look – Luzon Island, Part II

By Michael Mozdy

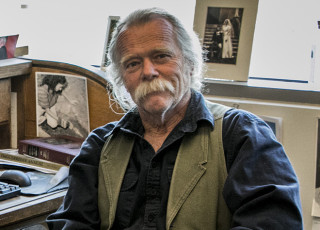

What draws our Curator of Vertebrate Zoology to Luzon island has a lot to do with its unique geography and climate (read more in Why Oceanic Islands Fascinate Us: Luzon Island, Part I), and these features lead to something called endemism. “When we say something is endemic to a certain place,” says Rickart, “we mean that it exists only in that one location on the planet.” He explains that while Utah has only 1 endemic animal (our illustrious Utah Prairie Dog), the Philippines have 154 endemic species – the greatest level of endemism of any country in the world.

Greater Luzon has 45 species of mammals endemic to the island, or 43% of the total mammal fauna. When you take out the flying mammals (lots and lots of bats), that figure skyrockets to 90% of the non-flying mammals being endemic to Luzon. This makes sense: with its deep underwater trenches, geologic isolation, and violent climate, it wouldn’t have been easy for non-flying species to hop, walk, or swim to this island before the time of human-assisted transport.

The western world started becoming interested in the unique Philippine fauna in the 1800s. European visitors found a number of the larger mammals like brown deer, warty pigs, civets, and macaques. They even catalogued the largest bat in the world – the golden-crowned flying fox – which weighs in at more than two pounds with a wingspan of nearly six feet. Although they seem formidable, “they’re really gentle creatures that eat fruit,” insists Rickart.

Golden-crowned flying fox

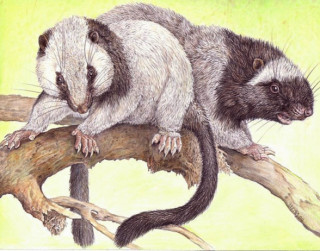

Then there are the giant “cloud rats,” some of which weigh as much as 6 pounds and are as big as house cats. Although they look much like squirrels, they are true rats, meaning they belong to the group of Old World rodents (Muroidea). The muroid family, in case you didn’t know, is huge. “Of the more than 5,000 mammals that are known to exist now,” explains Rickart, ”nearly one third of them are muroid rodents, and the largest one on earth lives in Luzon.”

Giant Cloud Rats

There are two primary subgroups of rodents on Luzon: the “tree rats” that include the giant cloud rats and their relatives, and the “earthworm mice” most of which, as their name implies, “make their living eating earthworms,” according to Rickart. Tree rats, on the other hand, subsist on plant matter. Even the big guys, the giant cloud rats, are “leaf specialists.” Both of these subgroups represent entire endemic clades, or branches on the tree of life that have evolved within the Philippines. They are the evolutionary descendants of just two ancient colonization events from mainland Asia. Together, these two groups of rodents account for 85% of the non-flying mammals on Luzon.

By the 1990s, scientists knew Luzon had some great diversity, and suspected that there might be more to find, but no one expected the bonanza that Rickart and his fellow researchers uncovered. They discovered two new genera and nineteen new species in the past fifteen years!

Among their finds are new species of “shrew rats” and several “shrew mice.” Many of these are highly specialized and clearly distinct, while others that may look very similar to the untrained eye, differ greatly genetically.

Shrew rat (on left) and shrew mouse (on right)

They also found the smallest Philippine rodents, the pygmy tree rats (genus Musseromys), which weigh as little as 15 grams! Oddly enough, this little fella belongs to the same group as the giant cloud rat, the largest rat in the world.

Pygmy cloud rat

One of the more interesting stories the coauthors relate in their book is about conservation and the challenges these small mammals have dealt with. There has been an incredible amount of habitat disruption, both from natural disasters (volcanic eruptions and typhoons) and those brought about by human activities (deforestation, human encroachment, and introduction of aggressive foreign species). As they studied communities of native species across gradients of habitat disturbance (from relatively undisturbed to completely deforested areas) they found some interesting and unexpected patterns.

Some native species had a very low tolerance for disturbance, but most native species could tolerate moderate levels of disturbance. Some native species were doing well in the edge zones at forest margins and a few were able to live in highly disturbed agricultural areas where invasive, non-native pests like Asian black rats and Polynesian rats cause great crop damage. Surprisingly, one of the most highly specialized groups of native rodents, the burrowing Striped rats (Chrotomys) can thrive in agricultural areas where they eat non-native earthworms abundant there and also the invasive snails that are pests of rice crops. Let's call them the home guard of Luzon...

Striped rat - defender of the natives

The most heartening evidence they found, however, was in previously deforested areas that had regenerated to early secondary forest. Here, native fauna moved right back in, out-competing the non-native species, and rebounding quite well. In short, the unique island mammals are not as fragile as many might have worried they were.

Regenerating forest

Data gathering over 30 years has brought us encouraging news about how conservation and habitat regeneration can encourage and re-invigorate populations of native mammal species. Ever the scientist, Rickart asks, “Why?” His hypothesis: “We think it’s because these remarkable animals have adapted to severe natural disturbances like earthquakes, typhoons, and volcanic eruptions, so there’s a sort of pre-adaptation to human disturbance.”

All of this makes Luzon one of the most fascinating places you might never had heard of.

The illustrations in this post were created by Velizar Simeonovski and first appear in The Mammals of Luzon, written by Eric Rickart, Lawrence Haney, and Danilo Balete. Photos were taken by Rickart, Haney, and Balete.

Michael Mozdy is a Digital Science Writer for The Natural History Museum of Utah, a part of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. Our mission is to illuminate the natural world and the place of humans within it. In addition to housing outstanding exhibits for the public, NHMU is a research museum. Learn more.