Digging Up the Past to Understand Our Climate Future

The fossil mammal Uintatherium is a distinctive Eocene beast. ©NHMU

By Riley Black

We are living in an era of extreme climate change. Human activities, such as dumping immense amounts of carbon dioxide into the air, are driving a sharp rise in global temperatures - by 2050, temperatures in Salt Lake City may be over 3°F hotter than they are today. How will ecology respond? While it's impossible to predict the future, paleontologists can still give us some idea of what to expect by looking to the past. There was a time when natural causes, rather than human ones, altered the global climate in a similar way, and studying the clues within those rocks can help us get some idea of what's in store over the coming decades and centuries.

"We are working in the Uinta Basin, about three hours east of Salt Lake City near Vernal," says Midwestern University paleontologist Beth Townsend. The area is famous for its dinosaurs, of course, but Townsend and her crew are working in rocks that were laid down millions of years after the mass extinction that ended the Age of Dinosaurs - a time known as the Eocene, 56 to 33.9 million years ago.

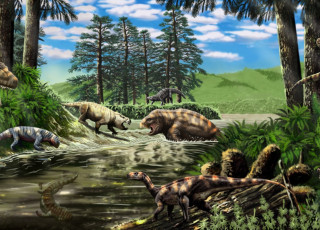

The Eocene was an important era for beasts. "The Eocene is distinctive because the modern orders of mammal start to appear at that time," Townsend says. "If you could visit that time, you could look at the animals around and say 'That's a little deer, a little monkey, a little horse.'" But that's hardly all. The Eocene saw some major swings in the global climate, and one event in particular is startlingly similar to what's happening today. "Taking climate data since 1898 and current science," Townsend says, "if we do nothing climate-wise, global temperatures will rise by about 7°F, and this is the same temperature increase we're seeing in the Eocene, only over 600,000 years instead of 200." It's as close as researchers can get to a preview of how the world might change as global temperatures continue to climb.

Understanding this event and its effects on life requires a multi-pronged approach. When Townsend and her crew return to the Uinta Basin this summer, the researchers will take stratigraphic sections of the rock, take samples of fossil pollen, document fossil sites, and more, threading all those sources of information together to help create a picture of environmental changes and life's response. And it's hard work. "The basin is a white and gray mud," Townsend says, "which is like walking on a super hot mirror." But it's worth it. There's a great deal to discover that previous crews have overlooked.

During the early 20th century, Townsend notes, paleontologists came to the Uinta basin looking for large, strange creatures for their museum halls. They were looking for animals like Uintatherium, a saber-toothed herbivore with six knob-like horns on its head. Researchers largely ignored the smaller mammals and other animals, such as early rodents, primates, and the early relatives of cats and dogs. Townsend's project is aiming to find more of these small animals, and so far the team has documents almost 300 fossil localities in the basin. By uncovering these creatures, understanding when they lived, and how their habitats changed, paleontologists can assemble a picture of how organisms respond to hotter climates over long time scales - an aid to conservationists looking to protect the world's biodiversity. And during a summer that's already marked by record-breaking heat, the quest to find these fossils is more important than ever.

Riley Black is the author of Skeleton Keys, My Beloved Brontosaurus, Prehistoric Predators, and a science writer for the Natural History Museum of Utah, a part of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. Our mission is to illuminate the natural world and the place of humans within it. In addition to housing outstanding exhibits for the public, NHMU is a research museum. Learn more.