The Utah Chocolate Story

© NHMU

Cacao pods growing on the plant, Theobroma cacao. Eco Chocolate Museum, Yucatán Peninsula. Photo: Enrique Pérez HuertaChocolate, a product of the cacao plant Theobroma cacao, has a long history with humans. As early as 1900 B.C., a prehistoric culture called the Mokaya from the Pacific coast of Chiapas, Mexico, were processing and consuming a liquid that seems to have been chocolate (“Oldest Chocolate in the New World,” Terry G. Powis, et. al., Antiquity Vol 81, Issue 314, 2007).

Cacao originated in the Amazon, and with the help of ancient people, made its way into Mesoamerica. Yet cacao only grows within 20 degrees latitude (north and south) of the equator. These finicky plants need light, high humidity, and constant, warm-to-hot temperatures all year long. Read Chocolate: Its Origins for more information.

If tropical areas are the best for growing cacao, we might expect that only ancient cultures close to the equator would be using it, but that’s not the case. Ours is the story of how cacao beans improbably found their way 1,500 miles north to the dry, hot, high altitude climate of Southeastern Utah in a time long before modern transportation.

Cacao in Chaco Canyon

The first hint of chocolate being used in the Southwestern U.S. came from New Mexico. In 2009, a researcher from the University of New Mexico named Patricia Crown published her findings of cacao residue on pottery from Chaco Canyon in New Mexico. These pottery vessels dated to around 1000 A.D. – a time when the Ancestral Puebloan people (also known as the Anasazi) were living there.

Read about Crown’s fascinating discovery: Cacao in Chaco Canyon.

Utah’s Cacao: the Oldest Yet Found in the United States

© NHMU

Reproduction of Mayan statue, cacao being used ceremonially. Eco Chocolate Museum, Yucatán Peninsula. Photo: Enrique Pérez HuertaBuilding on Crown’s research, Dorothy Washburn from the University of Pennsylvania tested shallow ceramic bowls of a distinctive type called “Abajo Red on Orange” from an ancestral Puebloan site in Southeastern Utah called Alkali Ridge site 13. Washburn found the markers for cacao – theobromine and caffeine – on 75% of the objects she tested.

In Mayan and Aztec cultures, chocolate was used by the social elite; the discovery of an exotic import like cacao in a typical Four Corners region settlement, with residues on many common vessels, surprised many archaeologists. The fact that the objects she tested date back to 780 A.D., over two centuries before the Chaco Canyon vessels, surprised them even more.

Washburn describes the thin-walled, red-on-orange pottery found at Alkali Ridge as being significantly different from any other in the region. Taken together with the discovery of cacao residue, her conclusion is that the bowls and the use of cacao are both the result of a migration of people from Mesoamerica.

Read about Washburn’s surprising and controversial discovery in Utah’s Ancient Cacao: A Surprising Find.

Tracing Cacao through Extensive Trade and Migrations

For cacao to travel from the Amazon to Mexico is understandable – the tropical parts of southern Mexico can support growing the plant, and extensive trade throughout Mayan and Aztec cultures would spread it. But to find cacao over 1,500 miles north of where it’s grown is pretty incredible. Even though the early cultivation of maize (corn) in the Southwest is known to have come from Mesoamerica, archaeologists have assumed that the ancient cultures of the southwest US developed and thrived in comparative isolation.

The discovery of chocolate in Utah has turned this assumption on its head. Washburn argues her discovery of cacao in Utah is evidence of a strong Mesoamerican influence on the Southwest through sustained contact and repeated migrations.

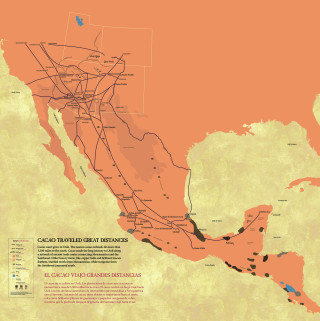

A picture of extensive trade emerges. Luxury goods like cacao, scarlet macaws from the rainforest, copper bells, and pyrite mirrors made the journey north from Mesoamerica while turquoise from the Southwest journeyed south. Researchers have pieced together enough evidence to outline trade routes as seen on the map below.

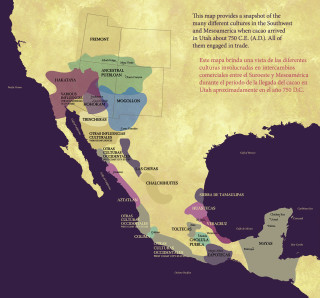

This evidence of extensive trade is bolstered when you consider the cultures and groups of people living throughout the Southwest and Mexico at the time of the Utah cacao find (750 A.D.). As the map below shows, many of these groups were adjacent to or overlapping each other, and all were engaged in extensive trade.

Continuing to Test for Cacao Use in Utah

One researcher at NHMU has been actively looking for evidence of chocolate in Utah since Washburn published her paper in 2013. NHMU archaeologist Glenna Nielsen-Grimm, with colleagues from BYU and Blanding, Utah, is conducting research in the field and looking at objects in Utah museums and private collections to test Washburn’s results and ideas.

Nielsen-Grimm focused on the idea of function when selecting vessels from the museum’s collection to test for cacao. For this reason, she chose items like a pestle for grinding cacao beans and serving vessels such as bowls, ladles, pitchers, and mugs.

Nielsen-Grimm collaborates with BYU scientist Richard Terry, who oversees the extraction and chemical analysis of the residues. After the first rounds of cacao tests from the NHMU collection returned negative results, Nielsen-Grimm and Terry took a hard look at their testing process. Terry and his students refined their extraction process and increased the sensitivity of the filters they use for their rinse water. They have determined a limit of detection that handles the issue of contamination (read Utah’s Ancient Cacao: A Surprising Find for a discussion of testing methods and their problems).

Nielsen-Grimm and Terry are looking to do more tests of museum artifacts in the future.

In the meantime, Nielsen-Grimm and her colleagues, including Ray and Deanne Matheny and Winston Hurst, are investigating sites in Montezuma Canyon, Utah, near Alkali Ridge. Three sites in particular, Cave Canyon Village, Monument Village and most recently Montezuma Village (named after Montezuma Creek, which runs through it), are under investigation.

Alkali Ridge, Monument Village, Cave Canyon Village, and Montezuma Village are located in Southeastern Utah. © NHMU

They have tested surface-level artifacts recovered from Montezuma Village, as well as ceramic sherds excavated from Cave Canyon and Monument Village. They have found positive evidence of cacao use in mug bases, bases of corrugated jars, and bases of Abajo red-on-orange and white ware bowls.

Nielsen-Grimm believes that testing artifacts directly from archaeological sites helps to lessen the chance that they are contaminated. When artifacts are stored or processed for museums, there is a chance they are cleaned and potential cacao residues are removed. There is also a chance that artifacts may pick up environmental contamination from the air or the people who handle them.

One of the Abajo red-on-orange bowls that tested positive for cacao residue. (Museum of Peoples and Cultures. MPC75.011.1372) Photo by Glenna Nielsen-Grimm. © NHMU

To date, Nielsen-Grimm and her colleagues have found evidence of cacao at three different village sites, all within 10 miles of each other and Alkali Ridge. This certainly seems to validate Washburn’s hypothesis that cacao did indeed travel up to Utah, and does lend credence to the hypothesis of an active connection or even migration of Mesoamerican peoples.

Red-on-orange pottery sherds that tested positive for cacao residue. © NHMU

Nielsen-Grimm is awaiting test results on another group of artifacts, and is hoping to find the elusive theophylline, which, in combination with theobromine and caffeine in the correct proportions, would be increasing proof of cacao trade.

A red-on-orange pottery sherd that tested positive for cacao residue. © NHMU.