The Art and Details of Scientific Illustration

By Michael Mozdy

Sometimes it’s difficult to get a photograph to reveal particular aspects of a plant or animal’s anatomy, and near impossible for the smaller building blocks of life like cells or DNA. Lucky for us, we have scientific illustrators who can bring to life so much of the world around us.

For millennia, illustrators have helped us envision the natural world. From the Greek physician Herophilos’s human dissections in the 4th century B.C. to John Wesley Powell’s expedition in Southern Utah in 1869, scientific illustration has shaped history and helped to pass scientific knowledge to future generations.

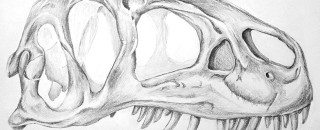

One scientific illustrator living and working in Utah recently taught illustration workshops during DinoFest 2017 and sketched an Allosaurus skull for the Natural History Museum of Utah. Natalia Wilkins-Tyler holds a science illustration masters certificate from Cal State Monterey Bay, and in addition to working as a contributing illustrator for NHMU, teaches botanical illustration at neighboring Red Butte Garden and Arboretum.

The time lapse video below shows Wilkins-Tyler’s work over two and a half hours to set up and sketch the Allosaurus skull (which, she notes, is unfinished). She claims that a full illustration (11x17 size) would have taken 20-30 hours to complete. To really bring the skull to life, she would add what she calls “sweet spots of detail,” as well as more darks and lights. These small but effective additions show contrast and the three-dimensional aspects of bones. The bone structure, she points out, “has a lot of pits, divots, creases, and lines in it,” and these elements help the viewer to understand the skull better.

Wilkins-Tyler explains that scientific illustrators must be incredibly accurate and highly detailed in their work. This takes a great deal of study, talking to researchers about the subject matter, and honing of observational skills. She says that being able to pick up on tiny differences and details is important to art in general, but in scientific illustration, “you really have to work on training your eye to draw what is actually there instead of what you see.”

This is an important distinction between art and scientific illustration. Impressionism, for instance, is an example of a visual art style where we see the artist’s interpretation of a scene or object. While this may be beautiful and employ colors and shapes we would normally not have imagined, Wilkins-Tyler notes that, if done by a scientific illustrator, “you would be inventing a new species.”

Put more succinctly, the Guild of Natural Science Illustrators states on its web page: “As art reflects culture, scientific illustration reflects the findings of science and technology.”

This is not to say that all scientific illustration must present a scenario as if it was just photographed. Scientific illustration is also a powerful portrayal of context, which goes a long way in helping the viewer understand the dimensions, utility, or interplay of the organisms being illustrated. Wilkins-Tyler elaborates with an example of a cell; if done all alone, outside of its environment, “it’s just a pretty picture, it doesn’t actually have meaning.”

Sometimes the power of illustration is that it can combine facts about an organism into one illustration as a compact way for understanding many facets at once. A good example is Wilkins-Tyler’s illustration of Satin Bower birds (below), which is able to accomplish many things at once: the differing anatomy and coloration of the male and female birds, the male’s habits of collecting baubles for the nest, the interaction of the two as the female surveys the nest, and even the dimensions and physical layout of the entrance to the nest.

Wilkins-Tyler has long held a love of botany, biology and art, which she credits to an early childhood visit to Costa Rica at the age of 6. These passions drive her curiosity and help her to maintain her focus on detail. She first worked for NHMU in 2012, while completing an internship for her masters degree. For 10 weeks, she worked with NHMU’s Chief Curator, Duncan Metcalfe, Ph.D., in Range Creek, Utah, where she illustrated rock art, granaries, and other natural history art. Her goal was to illustrate how pictographs would look if they were just painted.

NHMU greatly appreciates Wilkins-Tyler’s work, and we look forward to working with her more in the future.