Hide Your Stuff in Plain Sight: Up a 1,000-Foot Rock Face

By Michael Mozdy

Out in the rugged West Tavaputs Plateau of central Utah, we operate a remote research station called Range Creek. It occupies a large space, ranging from 10,000-foot mountain passes to 4,000-foot flood plains. It was once home to many Fremont Indian foragers/farmers, and we’ve found nearly 500 archaeological sites filled with fascinating hints at past life here.

A few of these sites are simple: a bundle of arrow shafts stuffed in a cliff crack, for instance. Others are nothing short of spectacular. Case in point: the cliffside granaries.

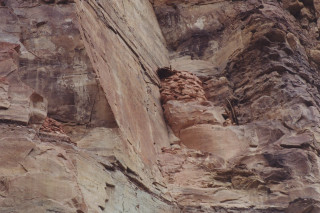

Some of the 55 granaries in Range Creek are 1,000 feet or more above the canyon floor, and most are located on the faces of tall cliffs that make up the canyon walls. We must use skilled climbers who rappel into these remote granaries to take pictures of the sites. Thankfully, our very own University of Utah geography professor Larry Coats happens to be a skilled climber and co-researcher at Range Creek.

These granaries are one type of storage we’ve found. The other types include smaller, more hidden caches and covered pits we call cists. These caches and cists, interestingly, are mostly not far from the settlements. So it seems that the Fremont were using two strategies: put valuable stuff in hard-to-reach but easy-to-see locations or the opposite: use easy-to-reach but hard-to-see smaller caches.

Many of us can understand a hidden place we can easily reach for our valuables. We do this today: jewelry boxes, safes, etc. But to put your stuff in barely accessible spots that everyone can see? That’s a bit of a head-scratcher.

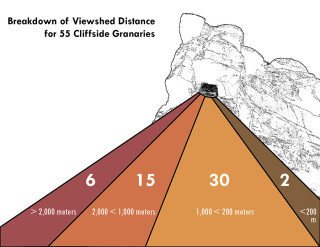

One of our researchers, Shannon Boomgarden, Ph.D., decided to quantify just how easy to see the cliffside granaries are. She conducted what is called a viewshed analysis. With a mix of ArcGIS modeling and physical measurements, Boomgarden determined that all of the granaries had a viewshed of at least 100 meters along the valley floor corridor and most were visible for more than 400 meters.

She didn’t stop there. She looked at how many residential sites are in each viewshed. 27 have one or two residential sites in lines of sight, while 23 have between three and eight.

Boomgarden’s hypothesis is that people could keep an eye on their storage sites while working in the fields and being at home.

So, these granaries turn out to be highly visible. “It’s incredible,” says Boomgarden. “Even when there was an opportunity to build one further back the cliffside in a more protected and secluded spot, they chose to build out on the most exposed and visible spot possible.”

Why would the Fremont choose to build granaries in this way? Boomgarden’s hypothesis is that people could keep an eye on their storage sites while working in the fields and being at home; and because the approach routes and granaries were so visible and difficult to get to, they had plenty of time to respond and reach the thieves if anyone dared.

The hypothesis reminds me of something the French philosopher Michel Foulcault writes in his seminal work, Discipline and Punish. He discusses a theoretical prison called the panopticon where prisoners are completely visible at all times from an easy vantage point. Foucault writes: “He who is subjected to a field of visibility, and who knows it, assumes responsibility for the constraints of power; he makes them play spontaneously upon himself…” In other words, by being so exposed, the prisoner effectively polices himself.

Foucault worries about how we might be subtly controlled through often unseen forces, but he also unveils some truths about human psychology: we act in seemingly unexpected ways when our actions are either hidden or made transparent.

Philosophers today have taken up the banner of panopticism while critiquing modern systems of digital surveillance. It’s a new form of exposure where our purchases, online searches, phone calls, even our physical location is made available to “unseen forces.” It’s easy to get a little paranoid about this new world of visibility, but maybe it’s not so new to be using the threat of visibility to keep people in line.

To me, it is incredible to look at Boomgarden’s work in Range Creek and see examples of panopticism dating back to pre-technological cultures (1050 A.D. is the rough date for most of the settlements). After all, what is at work in the cliffside granaries but people policing themselves because they would be made exposed and visible? Putting granaries there would certainly not deter rodents and other creatures. It’s clearly designed to be effective against humans.

This study is just one of many going on in Range Creek, and it is our great privilege to be a part of the science that reveals not just past cultures and creatures, but the creativity, intelligence, and craft that connects humans throughout our history on this planet.

Shannon Arnold-Boomgarden, Ph.D. is the Assistant Field School Director & NHMU Archaeology Lab Manager. In addition to running several research projects at Range Creek, she helps to survey new sections of Range Creek, re-survey highly visited sites, and run a field school for college students, training them in field research.

More pictures of Cliffside granaries in Range Creek:

Michael Mozdy is a Digital Science Writer for The Natural History Museum of Utah, a part of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. Our mission is to illuminate the natural world and the place of humans within it. In addition to housing outstanding exhibits for the public, NHMU is a research museum. Learn more.