Mountain Mahogany: One Tough Rose

By Michael Mozdy

Autumn is an incredible time to hike in Utah. The colors are bright, the air is cool, and often a newly whitecapped mountain framed in blue crowns the day. I like to measure the turning of the seasons in the rich smells of just-decaying organic matter on wet earth and the wide array of yellows, oranges, and reds in the foliage.

And greens, I have to add.

We notice greens mostly in our beloved conifers, but there's another evergreen that graces our western landscapes that is not a gymnosperm (conifer): the mountain mahogany. "We call these 'evergreen broadleaf,'" notes Mitch Power, the NHMU Botany Curator, "because they retain their leaves for more than one year." We have three species in Utah: Cercocarpus intricatus (dwarf mountain-mahogany), C. ledifolius (curl-leaf), and C. montanus (Alder-leaf).

This slow-growing member of the Rosaceae, or rose, family is a hearty and striking tree that I recently took time to know a little better.

When hiking with my wife to Mount Aire from Millcreek Canyon on a typically gorgeous fall day, we noticed a change in the plants around us at around 7,500 feet. At first, it was the spicy herbal scent in the air, and then it was the silver-barked, twisted form of the tree limbs, studded with dark green, leathery, lance-shaped leaves that caught my eye.

Panoramic view on Mt. Aire trail, September, 2016. Photo: Michael Mozdy.

This was Cercocarpus ledifolius, or Curl-Leaf Mountain Mahogany. As we walked up the dry, rocky path on this sunny day, we passed under and alongside many groves of mountain mahogany, and the effect was almost Mediterranean, as if we were walking through olive groves.

Hiking past Curl-Leaf Mountain Mahogany on the Mt. Aire trail. Photo: Michael Mozdy

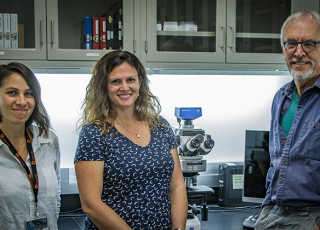

Elizabeth Johnson, the NHMU Collections Manager for the Garrett Herbarium, helped me identify the plant from my pictures, and she has her own story about how striking mountain mahogany can be in the landscape. "I was traveling with a colleague in Northwestern Nevada through rolling hills," she recalls, "and when we stopped to camp, we saw a great herd of antelope grazing with these large, umbrella-shaped mountain mahogany trees silhouetted against the sky. When the full moon rose and the coyotes began to howl, it was like we were transported to the African savannah."

The trees can be just as captivating up close. On our hike, we noticed the most fanciful, feathery plumes mixed within the leaves. These were the long styles of the trees' flowers. "These help with seed dispersal in the wind," explains Johnson.

They're a showy feature, but highly practical. Power notes: "These seeds can be dispersed up to 150 meters (450 feet) from the parent plant." That's a great benefit for this twisted, hearty plant that clutches to inhospitable mountainsides where not many other options exist for spreading seeds.

Feathery plume-like styles on a Curl-Leaf Mountain Mahogany. Photo: Michael Mozdy.

My friend, Paul, shared with me some much more striking photos he took this fall while hiking to Lone Peak. "We went through a grove in which the ground was covered almost like snow in feathery, curly seeds," he said. "In the evening light this was a sight to behold!"

Mountain mahogany seeds on the ground on trail to Lone Peak. Photos: Paul Zembruski.

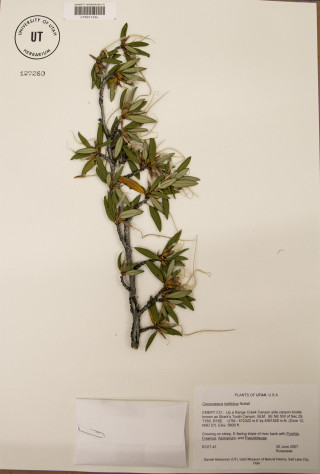

Johnson took me to the steel cabinets in the climate-controlled Garrett Herbarium collections room to show me some of the museum's specimens. We looked through several dozen herbarium sheets of Curl-Leaf Mountain Mahogany, and some dating back to the 1960s still retained the green color of the leaves. The long styles were also well-preserved, as shown in the 2007 specimen below.

Herbarium sheet for a 2007 Cercocarpus ledifolius specimen. © NHMU (click on image to enlarge).

Beyond its enchanting growth habit and feathery styles, Curl-Leaf Mountain Mahogany has some very practical and interesting features. First of all, it is found throughout the west, growing in some very dry, rocky environments. "It's one of few non-gymnosperm evergreens," explains Power, "and so this helps it both continue to photosynthesize and produce energy throughout the winter but also conserve energy by not having to grow new leaves each year. Other deciduous trees have to store up a ton of starch and pour it into the creation of new leaves." There's one evolutionary bonus point for the tree.

It is certainly resilient in inhospitable growing zones. Power elaborates: "I put it in the same category as Bristlecone pines - one of those species that is slow growing, super hardy, and perfectly suited for dry, rocky soils. These plants can also tolerate a huge range of diurnal and seasonal temperature variation, for example, from -3° C in January to 22.4º C in July." For these reasons, and the fact that they're drought-tolerant, Power notes that they'd be excellent xeriscaping plants for our yards, but few nurseries carry them because they're relatively slow growing.

It's indeed a slow grower that lives a long time. A Nevada study published in 1990 notes that the oldest tree in their study was 1,350 years old - which makes Curl-Leaf Mountain Mahogany one of the oldest known flowering plants (up there with olive trees and flowering figs). And this tree isn't that widely studied, so some trees in remote western areas may be even older.

The trees have a shrub-like growth habit when they're younger (and they're a good forage plant for mule deer), but as they age, they grow very upright and even establish a canopy that helps the mature trees outcompete the younger ones. What emerges is a picture of a super slow race to maturity - the tortoise race of the plant world.

Photo of a mature Curl-Leaf Mountain Mahogany, showing its umbrella-like canopy structure. Photo: Sheri Hagwood, hosted by the USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database.

The wood of Curl-Leaf Mountain Mahogany is incredibly dense. So dense, in fact, that it sinks in water! This makes the wood great fuel because it burns long and very hot.

Slow, dense growth over many centuries has other implications for scientists. Power studies plant ecosystems and how they evolve over millennia alongside natural disturbances like fire and hurricanes (read Hunting for Charcoal in Bolivian Chiquitano Forests for more about Power's research). In some cases, his work involves examining tree ring data. Oak is the most reliable for tree ring data while birch and willow are too erratic of growers to be used. "Some of my colleagues at Utah State have examined mountain mahogany tree rings," relates Power. "It's difficult because the rings are so tightly packed and thin, but using a microscope, you can gather good data," he notes.

Humans have found good uses for Curl-Leaf Mountain Mahogany for a long time. Many Native American groups use the bark for medicinal purposes. The Goshute, Paiute, and Shoshone peoples crushed up dried or slightly burned bark and used it as a dressing for burns. What's more, the Paiute and Shoshone used a decoction of bark or wood to treat many ailments, including coughs, colds, cuts, wounds, stomach aches, diarrhea, tuberculosis, and even an "unfailing cure for syphilis."1 The hard wood was also used to make bows and arrowheads. Even further back in time, prehistoric people used wood from this tree for digging sticks and other durable tools because it's so hard.

All in all, I think Curl-Leaf Mountain Mahogany is a beautiful and beguiling tree - one that evokes exotic landscapes from far-off lands yet one that is perfectly suited to growing here in our western mountains. It's a distinctive marker for our land and there may be much more to learn from it.

1 Train, Percy, James R. Henrichs and W. Andrew Archer, 1941, Medicinal Uses of Plants by Indian Tribes of Nevada, Washington DC. U.S. Department of Agriculture, page 53-55

Michael Mozdy is a Digital Science Writer for The Natural History Museum of Utah, a part of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. Our mission is to illuminate the natural world and the place of humans within it. In addition to housing outstanding exhibits for the public, NHMU is a research museum. Learn more.