New Study Reveals Secrets of Crocodiles’ Smile

University of Utah graduate student Keegan Melstrom studied fossil crocodile teeth to better understand the reptiles' diets. Photo ©NHMU

By Riley Black

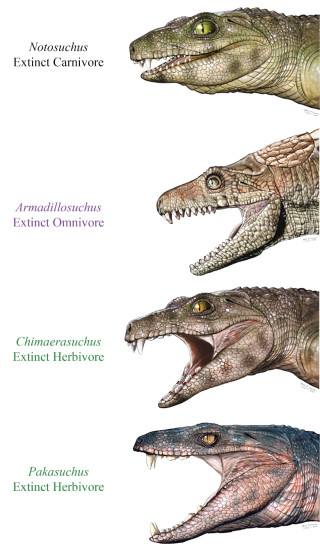

Today’s crocodylians all have similar toothy smiles. Whether it’s a Nile crocodile, American alligator, or a gharial, all living members of their reptilian family have pointy, cone-shaped teeth good for snatching wriggling prey, and fitting the carnivores' roles as aquatic ambush predators. But crocodile relatives of the deep past had a much broader array of smiles. Some had teeth fitted to nipping plants. Others had toolkits of varied teeth that were more like what you’re expect of a mammal. And others had shearing, knife-like teeth that resembled those of predatory dinosaurs.

But how to tell who ate what? By using high-definition 3D mapping technology, University of Utah graduate student Keegan Melstrom and Museum chief curator Randall Irmis have been able to take a new look at what some very old crocs were dining on.

“The original idea came in 2011,” Melstrom says, when he was an undergraduate and saw a conference presentation about a small extinct croc called Pakasuchus. Found in Tanzania, this reptile had a varied dental array resembling the piercing and crushing teeth of mammals, and it made quite an impression on Melstrom. Irmis had also long been interested in the varied diets of prehistoric crocs, as well, and when Melstrom started his graduate studies at the University of Utah the threads came together in the new project. “It was really cool for Keegan to take the reins and run with it for his master’s thesis,” Irmis says.

The tale is in the teeth. Melstrom and Irmis studied over a hundred teeth from fossils of sixteen species of crocodile relatives found all over the world, using 3D scans and casts from multiple institutions and researchers. Some teeth in the sample were pointed, like those of modern crocodylians, but others looked more like the crushing molars and canine teeth of mammals, as well as other shapes that have been difficult to interpret. “We see all these tooth shapes in the history of reptile evolution, and some of them are fairly straightforward, but others just have no comparison,” Irmis says.

To cut through the mystery, Melstrom and Irmis took highly-detailed digital scans of the teeth and analyzed them through a method called OPCR. The technique treats the teeth as miniature mountains, measuring how complex each tooth shape is. Studies of modern mammals and reptiles have shown that the more complicated the teeth are, the more plant material the animal eats, Melstrom says, and so the crocodile teeth results were interpreted based upon what we understand about living species.

The researchers' results are published in Current Biology. Contrary to the common perception that crocodilians have gone along unchanged since their origin over 200 million years ago, Melstrom and Irmis found further evidence that crocs of the past were extremely varied and would have looked strange to us. Although there were semi-aquatic ambush predators during the age of dinosaurs (Mesozoic Era), there were also crocodiles relatives that lived on land and were more omnivorous in their tastes. There were even some that primarily dined at the prehistoric salad bar. Herbivorous crocodile relatives evolved at least three times during the Mesozoic, Melstrom and Irmis found, and possibly as many times as six.

There were some surprises in the results. A crocodile called Notosuchus from Argentina was previously thought to be an herbivore, for example, “but my work strongly suggests it’s a carnivore,” Melstrom says. “Some of the crocs that people thought were strict herbivores are more likely to be insectivores and omnivores,” Irmis adds. And in the case of a strange tooth from an unnamed Jurassic species from Arizona, Melstrom notes that the level of tooth complexity rivals that of any living reptile and approaches the molar complexity of some plant-eating mammals.

The herbivorous crocodile relatives, in particular, drag out another mystery. What led to the repeated evolution of plant-eating crocs? Though it might be tempting to think that these herbivorous reptiles evolved in places where plant-eating mammal relatives were absent, the fossil record doesn’t bear out that idea. The herbivorous crocodilians lived alongside plant-eating mammal relatives, potentially picking from a similar bill of prehistoric fare. “What this says to me is that you don’t need a single special environment for this to happen,” Melstrom says. “It’s something that’s a dietary strategy that’s really successful.” Further proof that getting to know the crocodiles of the past requires looking them in the mouth.

Riley Black is the author of Skeleton Keys, My Beloved Brontosaurus, Prehistoric Predators, and a science writer for the Natural History Museum of Utah, a part of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. Our mission is to illuminate the natural world and the place of humans within it. In addition to housing outstanding exhibits for the public, NHMU is a research museum. Learn more.