Ten Natural History Discoveries of the Decade

The discovery that giraffes hum was just one of the most fascinating natural history finds of the decade. Credit: Riley Black

By Riley Black

Our world is a vibrant one, full of fantastic organisms. New species are being discovered from ocean depths to people’s backyards, and even familiar forms of life can hold surprises. As we prepare to ring in 2020, here’s a recap of some of the most amazing natural history finds of the last decade.

1. Giraffes Hum

What sound does a giraffe make? The question sounds like a riddle, especially because zoologists long thought that these long-necked beasts were silent. But in 2015 zookeepers made a discovery that had eluded experts for centuries. During the night, giraffes hum.

2. Enter the Olinguito

In the mountain forests of the Andes, there lives one of the cutest mammals to have ever evolved. Called the olinguito, this raccoon relative took the internet by storm when it was revealed to the public in 2013. It was also the first member of the carnivoan family to be discovered in the Western Hemisphere in 35 years, making this fruit-noshing fuzzball quite a find.

3. Silkhenge

What in the world makes little circus tents in the rainforest? In 2013, zoologists and entomologists were confounded by a phenomenon never seen before – a little tower made of silk surrounded by a fence of smaller structures. No one had seen such a structure before or knew what sort of organism made it, or why. But the mystery was soon solved. The little silkhenge structures are made by forest spiders around their eggs, although scientists are still searching for the exact spider species that constructs them.

4. A New Passionflower Blooms

The jungles of South America were certainly hot spots for discovery in the past decade. And not just for animals. In 2013 botanists described a new species of passionflower from a forest that had grown over an old bauxite mine. New things can grow in familiar places.

5. Crocodiles Gallop, but Alligators Don’t

Galloping, bounding crocodiles might seem like a bit from an old cartoon, but truth, in this case, is stranger than fiction. A study published just this year indicates that at least seven crocodile species are able to speed along in a bounding motion, hinting that other species can, too. Strangely, alligators don’t gallop but can attain similar speeds at a trot.

6. How the Thresher Shark Threshes

Thresher sharks got their name for the long lobes of their tails, which were thought to act like whips to stun fish. But no scientist had actually recording them doing so. That changed in 2013, when new video of the behavior finally surfaced. The sharks really do deserve their name.

7. Back From the Dead

Sometimes lost species reappear. The pygmy goosefoot, an herb on New Zealand’s South Island, was thought to have gone extinct half a century ago. But botanists relocated the plant in 2015, perhaps underscoring the adage “It’s always in the last place you look.”

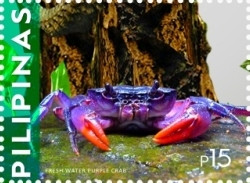

8. Purple Crabs Come Ashore

Most of the habitable space on our planet is in water, so it’s no surprise that researchers are still racking up new species from depths shallow to extreme. In 2012, to pick just one example, invertebrate experts named several species of strikingly purple crabs from the freshwater habitats of Palawan in the Philippines.

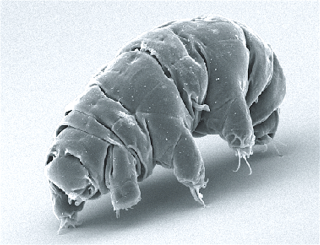

9. New Species Far… and Near

Not all unknown species are hiding in distant forests or inky depths. They may be as close as the parking lot outside your home. Just last year a researcher in Japan found a new species of “water bear” – or microscopic animals called tardigrades – on moss scraped up outside their apartment. This previously-unknown species also had odd eggs with spaghetti-like tendrils, which had never been seen before.

10. Most Species Are Undiscovered

Despite centuries of collection and study, most species on the planet have yet to be discovered. A paper published in 2011 proposed that approximately 81% of living species are completely unknown, and that’s not counting all the microorganisms that might add trillions more to that figure. There's still a whole wide world of unknown species to explore.

Riley Black is the author of Skeleton Keys, My Beloved Brontosaurus, Prehistoric Predators, and a science writer for the Natural History Museum of Utah, a part of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. Our mission is to illuminate the natural world and the place of humans within it. In addition to housing outstanding exhibits for the public, NHMU is a research museum. Learn more.