Writer and Sleuth Jason Felch Pieces Together the Antiquities Black Market

Author and investigator Jason Felch.

Jason Felch's NHMU Lecture Series appearance is available to view here.

Learn more about other speakers featured in the 2023 Lecture Series: Frontlines of Archaeology.

By Michael Mozdy

Starting in 2005, investigative reporter Jason Felch helped to break open a sordid tale of antiquities curators, shady middlemen, and modern looted artifacts in museums across the USA. Over the next seven years, Felch and his co-authors published nearly 40 articles in the LA Times, many of them front page stories. The tale was so complex that it took a book, Chasing Aphrodite: The Hunt for Looted Antiquities at the World’s Richest Museum, to lay out the full scope of the decades-long saga.

It’s a heck of a read.

“A lot of people are interested in the art world because of the glamor,” Felch relates. “But it is probably the world’s biggest unregulated market – as a result of that, a lot of shady stuff happens just a layer or two below the glitz.” As with any other business market, people will find ways to make money that are unethical and even completely counterfeit. The difference is the reverence given to these objects at the end of the line, in museums and collections. “This is great for storytelling,” Felch relates, “but also for understanding how the world works.”

But to say that Felch “broke” the story is not exactly accurate. The Italian and Greek authorities had been cracking into the story for decades by the time Felch came upon it, but his genius rests in the careful and dogged work of connecting stories and characters in order to bring the scandal to public attention. It is a vast web of criminal activity with a cast of disparate characters: poor villagers, career crooks, rich collectors, and self-righteous museum heads. What’s more, their culpability ranges from unwitting and contrite accomplices to outrageously deceptive con-men.

Felch had to wade through rivers of Italian court documents, interview shifty staff at the beleaguered Getty Museum, and even meet with looters and middlemen with ties to the Mafia. Investigative reporters like Felch face very real danger; it’s not a job for everyone.

“The investigative reporter is a rare and curious creature even within the newsroom,” Felch admits. While other reporters write daily stories, investigative reporters will work months on end before publishing a single word. “It’s a certain personality type, a combination of two things,” he explains. “One is a chip on their shoulder – a desire to hold institutions around you accountable and make sure everyone is playing by the same rules. That means that you probably lean into situations of conflict that other people would flee from. The other is an inherent inquisitiveness, tending towards obsessive compulsive behaviors, where you are searching for a truth and are willing to dig through 10,000 pages to find it.”

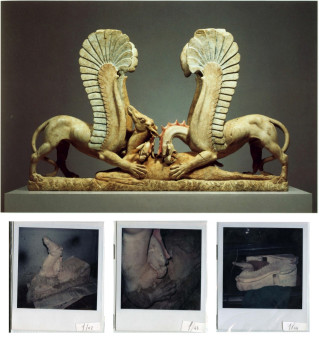

These images of are part of the story Felch tells in his book “Chasing Aphrodite.” The top photo is the complete sculpture “Two Griffins Attacking a Doe” as displayed at the Getty Museum while the three Polaroid photos on bottom were found in the warehouse of a black market dealer, Giacomo Medici, when the Italian police raided it. Looters discovered this 4th century BC sculptural group, in pieces, in a tomb near Ascoli Satriano, in Foggia, Italy, between 1976 and 1978 and sold it to dealer Giacomo Medici, who sold it to dealers Robin Symes and Christos Michaelides (partners). Symes and Michaelides then sold it to collector Maurice Tempelsman, who later sold it to the Getty Museum for $6.4 million. The Italian state repatriated the sculptural group from the Getty Museum in 2007 and it is now on permanent display in the local museum of Ascoli Satriano. Images from traffickingculture.org.

From the Mediterranean Sea to the Gulf of Thailand

Felch has stuck with the theme of looted antiquities, but has shifted his focus to South and Southeast Asia over the past decade. He will speak on February 21, 2023 at NHMU to share his latest research in a talk entitled, “Chasing Shiva: The Hunt for Looted South and Southeast Asia Antiquities.” He describes the talk as a true crime story told in case studies of three looted Asian masterpieces: a Shiva, Buddha and Duryodhana.

He notes that there are similarities with the looting of Western artifacts from Italy and Greece. Particularly, there is a pattern of dispersed looters funneling their finds to local middle men who then use transit companies to store them, clean them, and falsify histories for them. Finally, there is the fact that private collectors and museums fuel the black market with their insatiable demand for these antiquities.

“The differences,” he notes, “are cultural.” While ancient Greece and Rome are considered “dead” cultures, “in South and Southeast Asia, the artworks being stolen are often the gods from active temples,” Felch explains. “Not just symbols of gods, but the actual gods for these villagers.” Felch emphasizes that the sense of harm is much greater for these living cultures.

Archaeologists and ethnographers wholeheartedly agree. Archaeologists study past cultures and an excavation is done very carefully in order to preserve the context of every object. Subtle clues of positioning around structures, layers of deposition, and even molecular residues provide invaluable clues as to how ancient cultures lived, worked, worshipped, and more. Looting, in an archaeologist’s eyes, is an extreme form of violence to this entire mission of understanding.

Ethnographers study living cultures, and have definitively replaced a mindset of the colonizer with a mindset of respect. History is littered with encroaching cultures taking objects from others as their “right” as the dominant power. Thankfully, today that perspective is seen as wrong and unethical. To take an object from a living culture – regardless of its cultural importance – without a dialogue for understanding its context as well as explicit permission is seen not just as stealing, but also exploitation.

(As a note, this is why the NHMU ethnography department works so hard with living Native American cultures to ensure the collections are managed for the benefit of Native as well as non-Native cultures. Only when objects have been explained by the cultures themselves and been explicitly permitted are they exhibited.)

To Felch’s point, the crime of stealing artistic objects in Southeast Asia is amplified by the fact that they hold ultimate religious significance for the people.

Picture and caption from Felch’s website chasingaphrodite.org: “This 900-year-old bronze statue of Dancing Shiva, shown on display at the National Gallery of Australia, was stolen from a temple in Tamil Nadu, India shortly before the museum acquired it, new records show.”

What Should Museums Do?

In fact, the old rationale for acquiring artifacts from “dead” cultures is increasingly under fire. Greek and Italian authorities claim that these artifacts are their cultural heritage, not separate from them or in any way “up for grabs.” The ethical consequences are clear: if museums are to ask permission of living cultures like Native Americans, shouldn’t they ask the same of living cultures with ties to discovered ancient artifacts? But where does it end? Can’t many other cultures tie themselves to artifacts found in their geographic region? Does this spell the end of museums displaying foreign artifacts, or any ancient art?

Museums around the world are grappling with these very questions.

In just the past 10 years, the Getty, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and several others have returned ancient art found to have been looted. Another example: the Parthenon Marbles (“Elgin Marbles”), chipped off the Acropolis of Athens in 1801 by Lord Elgin, when Greece was under Ottoman control, and displayed at the British Museum since 1817. Even these hallowed objects are suddenly under discussion by the British Museum and the Greek government, which claims they form inseparable parts of the monument and must be returned. The British Museum has been ignoring requests to restore the Parthenon Marbles since 1835! Pangs of conscience by museum curators have been around for a long time, so what makes the present moment any different?

There is a good argument to be made that thanks to journalism like Felch’s, a type of tipping point has been reached. “There seems to be a global reckoning about antiquities that wasn’t there even 5 years ago, much less 15 years ago,” Felch agrees. Since the art market is unregulated, “only public pressure moves the needle; for many years there was little to no law enforcement attention to this issue.” he adds.

Given his unique perspective knowing the seedy underbelly of the antiquities market, Felch is a good person to ask about what museums should be doing. He agrees that a strong acquisitions policy is important, particularly in asking good questions before buying or taking objects on loan. But he notes that forged histories are common and that art curators are often not as good at investigating provenance as they are in building up collections. Plus, all museums and the professional societies to which they belong have ethics policies, yet Felch points out those are at times respected until a really spectacular object comes up for sale.

Felch thinks that the best result of the scandals over the past 15 years is an existential one. “Museums arose in the Enlightenment as showcases of empire,” he points out. “A tradition of ‘having the best stuff’ became self-defining for museums and really got them away from their purpose.” The scandals, he says, have “led museums to rethink their mission and their success at meeting their goals.”

The goal is not to stop displaying cultural artifacts.

Felch sees “a crucial role” in the display of cultural objects by museums. “Where else are people in Salt Lake City going to learn about Cambodia other than your institution?” he asks. “You can show them the material culture and help spark an interest in what’s going on outside our everyday world.”

The traveling Angkor exhibit at NHMU, in particular, is a model of good museum practice. The National Museum of Cambodia produced the exhibit and owns the objects, while the exhibit travels around the world to give as many people as possible exposure to its unique story. Felch details why this model is so important: “It embraces the owners of the culture, it centers their voice in the discussion of those objects, and there’s no black market involved.”

“We want objects to move around like this,” he adds. “People need to see what Cambodian culture is all about and these types of exhibitions are the way to do it.”

Felch continues to live and work in Los Angeles, where he has started a business intelligence firm called Open Source Research. The name says it all: research into corporate misbehavior around the world using publicly available sources like media clips, police reports, etc. His clients are nonprofits with policy goals and lawyers looking for fact finding help.

“People who succeed in his field are the same who succeed as investigative reporters,” he states, “they are self-motivated to solve puzzles and are willing to stay up all night to do it.”

After seeing the results of his journalism, it’s hard not to see that puzzle masters like Felch help to change our society for the better. We are made aware of criminal deeds and are able to apply pressure for institutions to change.

“Journalism’s role is to find and tell inconvenient truths,” Felch says. “We describe the way the world really works, not the way we wish it worked.”

Jason Felch's NHMU Lecture Series appearance is available to view here.

Learn more about other speakers featured in the NHMU Lecture Series.

Michael Mozdy is the Associate Director for Science Communications in the Department of Radiology and Imaging Sciences at the University of Utah and a part-time contributor to the Natural History Museum of Utah. Our mission is to illuminate the natural world and the place of humans within it. In addition to housing outstanding exhibits for the public, NHMU is a research museum. Learn more.