The Dracula of Wasps

By Michael Mozdy

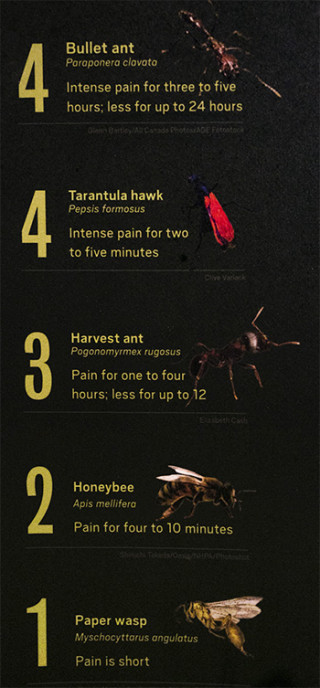

Living among us in Utah is a giant wasp with the most painful sting in the entire catalog of known bug bites and stings. Like a classic horror novel with a strangely beautiful antagonist, the tarantula hawk plays out her macabre story while we stumble heedlessly through our days.*

The name tarantula hawk is descriptive of a fierce and precise predator, but this is a type of spider wasp, not a bird. Pepsis grossa and Pepsis thisbe are the most common species, the large ones growing to an absurd two inches in length. Their bodies are a midnight blue and they're topped with striking orange or amber wings. The color scheme is another of nature's "don't mess with me" signals.

Tarantula hawk wasp. © NHMU.

The female wasp hunts tarantulas and can be seen scuttling along the ground during the hunt. When she finds females in their burrows, she boldly enters, chases them into the open, and then attacks. She may also find male tarantulas out looking for a mate. The tarantula hawk's terrible sting paralyzes the spider - a sting from which it will never recover.

She then drags the hapless arachnid back to its burrow, now a burial vault, or in the case of the males, she'll prepare a brooding nest in the ground. In this darkened chamber, the grisly ceremony begins. She lays a single egg on the spider's abdomen and then covers the entrance to the nest. When the egg hatches, the larva makes a hole in the paralyzed but still alive tarantula's abdomen and proceeds to "feed ravenously," avoiding vital organs in order to keep the tarantula alive as long as possible. After several (agonizing) weeks, the larva pupates and eventually an adult wasp exits the tarantula husk. Now those are some rough facts of life!

I've never felt so much compassion for a tarantula.

Tarantula hawk wasp. © NHMU.

The male tarantula hawk wasps do not sting, and the females rarely sting humans without being provoked. That being said, when they do sting, you'll feel it. One researcher described it this way: "To me, the pain is like an electric wand that hits you, inducing an immediate, excruciating pain that simply shuts down one’s ability to do anything, except, perhaps, scream. Mental discipline simply does not work in these situations."

After all the pain (which surprisingly lasts only two to five minutes), you can find solace in the fact that their venom isn't very lethal. So while you'll feel like you're dying, you probably won't.

Despite its nasty sting, Christy Bills, NHMU's Invertebrate Collections Manager, waxes poetically about the tarantula hawk: "They're gorgeous. By weight, they're the largest wasp in the state, and arguably the loveliest." She adds that they're not curious about people or our food, so they don't linger around us (unlike my backyard yellow jackets, who won't stay away when I barbeque). As a result, stings are rare.

I first caught an interest in the tarantula hawk while checking out The Power of Poison exhibit developed by the American Natural History Museum in New York (on display at NHMU Oct. 15, 2016 - April 16, 2017). The exhibit is seriously fascinating - I could spend four hours exploring and feel like there's still more to learn. The piece that caught my eye is a short pain scale that rates insect bites from paper wasp to an ant that you don't ever want to encounter. On the left is a picture of the scale.

Incredibly, there are researchers who inflict these bites and stings on themselves so that we can all "rest easy" with the knowledge of which is worse. In my book, this ranks up there on the world's worst jobs list (or most insanely devoted to science). Doug Fabrizio, host of Radio West on KUER, recently interviewed one of these entomologists about the work of getting stung for science.

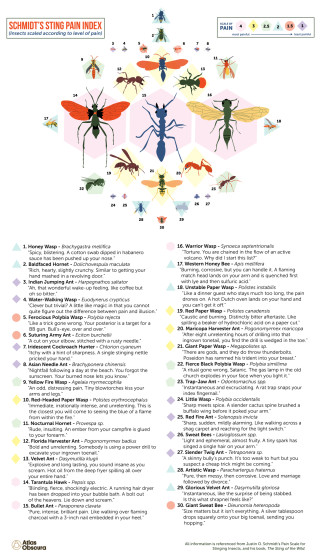

One of the most avid of these researchers, Justin Schmidt, has been willfully bitten, stung, and otherwise hurt for the cause over 1,000 times. A biologist at Southwestern Biological Institute and researcher in the entomology department at the University of Arizona, he eventually created Schmidt's Sting Pain Index, known for its downright poetic descriptions of stings. If a one-to-four rating scale seems arbitrary to you, reading through Schmidt's descriptions of the type of pain he felt with each sting helps to justify the number value. It also makes me all the more thankful to be writing about these things from a distance.

The insect sting/bite pain scale from the Power of Poison Exhibit. © NHMU.

Graphic describing Schmidt's Sting Pain Index, by Michelle Enemark / Atlas Obscura. Reproduced with permission.

* Authors acknowledgement: a huge amount of anthropomorphizing the wasp was used in this post, partly in honor of the Halloween holiday, my apologies to this marvelous creature.

The Power of Poison is a special exhibition that comes to us from the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, on exhibition at NHMU from October 15, 2016 through April 16, 2017. Learn more.

Michael Mozdy is a Digital Science Writer for The Natural History Museum of Utah, a part of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. Our mission is to illuminate the natural world and the place of humans within it. In addition to housing outstanding exhibits for the public, NHMU is a research museum. Learn more.