Looking Beyond the Temples at the People of Angkor – with Alison Carter, PhD

Artists’ reconstruction of medieval Angkorian life. Image via virtualangkor.com

By Michael Mozdy

In the year 1300 CE, London had 30,000 inhabitants. Paris boasted 80,000, while Cairo is estimated to have upwards of 360,000 people. Dwarfing all of these, an astounding 900,000 people may have lived in the area we call Angkor in present-day Cambodia. It was perhaps the greatest city of the medieval period, covering an area as large as Denver, CO and ruled by a succession of Hindu and Buddhist god-kings.

Angkor is best known for its temples: 72 major ones and several hundred minor temple sites. The 400-acre main Angkor Wat temple is rightfully considered a treasure of religious architecture, designed to symbolize Mount Meru, the home of the gods, with five giant, beehive-like towers rising out of the center in the shape of a lotus bud. The stone throughout this largest religious site in the world is intricately carved, mirroring the lush jungle vegetation surrounding the temple.

Angkor is an archaeologist’s dream, and a few of them are looking beyond the temples that draw 2.5 million tourists a year to better understand the people who lived and worked there. One of these archaeologists is Alison Carter, PhD.

Alison is an Assistant Professor of Anthropology at the University of Oregon, and her specialization is the evolution of complex societies in Southeast Asia. Alongside several other researchers from Cambodia and around the globe, she collaborates on the archaeological effort known as the Greater Angkor Project. She is currently the Principal Investigator and Co-Director of P'teah Cambodia (ProjecT Excavating Ancient Households), a project investigating Pre-Angkorian, Angkorian, and Post-Angkorian residential spaces in Battambang Province.

Alison and her collaborators are piecing together the everyday lives of people in medieval Angkor.

Inside Angkor

Much of what is known about Angkor comes from inscriptions on the temples and on upright stone slabs called stelae. These inscriptions talk about the royalty, the time periods for construction, and in a few rare cases, the vast amount of people who lived there and supported the religious function of the temples.

But looking around Angkor today, you don’t see evidence of housing for up to 900,000 people.

“It’s a challenge to find out where these people were living and retrieve good data,” Alison admits. “Their houses and much of their material culture were made of organic material that decomposes. Plus, much of the landscape is heavily forested.”

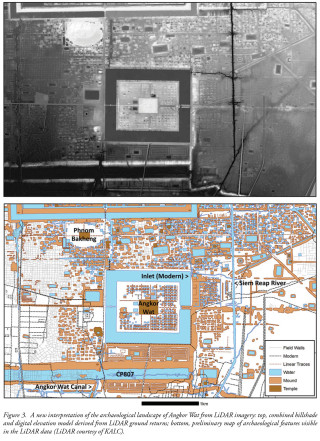

Thankfully, advent of LiDAR – that is, Light Detection and Ranging, which uses thousands of laser pulses from surveying aircraft – has been a game-changer for the archaeologists involved in the Greater Angkor Project. The data collected from LiDAR allows researchers to “strip away” the signatures of the vegetation to reveal the ground underneath and all of the ways humans have manipulated the earth.

In Angkor, LiDAR revealed strikingly ordered temple complexes including rectangular ponds and regularly spaced mounds that archaeologists believe represent a single household occupation. “We now have a clear view of a very well planned, orthogonal landscape showing these mounds and depressions,” Alison explains. “All of the temples have this type of occupation, and you can even see similar patterns outside of the temple grounds in the surrounding landscape.”

Figure and caption published in: Evans, D., & Fletcher, R. (2015). The landscape of Angkor Wat redefined. Antiquity, 89(348), 1402-1419. doi:10.15184/aqy.2015.157

Alison’s initial work in Angkor centered on the excavation of mounds within the Angkor Wat temple. She and her collaborators were able to find evidence of how a typical home would be organized and they extrapolated much from the pottery and building materials they found.

They learned that medieval Angkorians used castoff stone from the temples to help build their homes; that they had household gardens but likely brought in rice from outside the temple grounds; and, since cotton seed fragments were found in two separate temple mound habitations from different time periods, that cotton processing was prevalent and may have represented an economic enterprise for households.

She explains the sublime feeling of coming face-to-face with simple implements they unearthed: “There is something very special about looking at a vessel that someone else held and used and having the centuries that separate us just melt away.”

Alison Carter, PhD (pointing) doing field work in Cambodia with her co-investigator, Miriam Stark, PhD (in purple scarf). They are speaking with His Excellency Prak Sonnara from the Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts. Photo courtesy Alison Carter.

Outside Angkor

This work helped Alison understand the hierarchical society that supported the temples, but she wondered about life outside of “downtown” Angkor. After all, the Angkorian Empire spanned much of what is today the nation of Cambodia. What would life be like in the more rural part of the kingdom that supported the capital?

“In 2018,” she says, “my collaborator Miriam Stark from the University of Hawaii and I decided to shift to a provincial site, a major rice growing region that we presume would have been strategically important to the Angkorians.” The site they chose was across Tonlé Sap Lake in a village called Baset, in Battambang Province. In the early 11th century, King Suryavarman I had a temple built there.

“People were living there for centuries before the temple was built,” she says, “and we were very interested in knowing what it meant to get incorporated into the Angkor Empire.” While these people were likely speaking the same language and had similar cultural practices, they seemed to be fairly independent. “So what does it mean when the king comes to build a temple in your village?” Alison asks.

This work is ongoing, but one thing they discovered right away is that the soil is different from Angkor Wat. It’s much better for preserving organic material. “We are getting a lot more garbage, essentially,” she states matter-of-factly, “which is what every archaeologist wants.” They have found animal bone and plant remains that give them a sense of the people’s diet. Other remains help to explain everyday activities. “For example, we found a little fishing hook and fish remains, spindle whorls for spinning fibers, and even cotton seeds.”

Anti-Colonial Archaeology

Troubled Past

Sadly, Cambodia has experienced a terribly tumultuous modern period. It struggled against Vietnamese (and sometimes Thai) occupation throughout the 1700s and 1800s until becoming a French protectorate (i.e., colony) in 1863. In World War II, Cambodia was occupied by the Japanese and then again by the French until gaining independence in 1953. Just 17 years later, a brutal civil war and bombing by U.S. forces was a foretaste of the atrocities the country experienced during the genocidal reign of the Khmer Rouge.

The Khmer Rouge is the popular name given to the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK). Led by the man Pol Pot, who cited Stalin and Mao as major influences, Pol Pot tried to create a completely agrarian, self-sufficient society with no Western influence. Immediately upon coming to power in 1975, the Khmer Rouge forced citizens out of the cities into the countryside and instituted brutal work camps. Comprised of mainly uneducated, rural people-turned-soldiers, the Khmer Rouge distrusted those with education, executing them on the spot. Even those people who were stereotypically thought of as having intellectual qualities, such as wearing glasses or speaking multiple languages, were executed out of fear that they would rebel against the Khmer Rouge.

By 1979, when the Khmer Rouge was finally ousted from leading the government with the help of Vietnamese forces, approximately 2 million Cambodians had been killed by their own leaders. Sadly, the Khmer Rouge was never officially disarmed and disbanded, and the movement remained strong in the rural provinces up through the 1990s. While its leaders finally met international tribunal justice in the early 2000s, the country continues to have contentious internal politics and strained relations with its neighbors Thailand and Vietnam.

Alison’s work in Prasat Baset is complicated by the fact that a modern village currently occupies the entire medieval village site. “We’re essentially working in people’s back yards,” she laughs, “but it’s been an interesting and wonderful process so far.”

Alison’s project co-Director, Miriam Stark, was among the first Western archaeologists who were welcomed to work in Cambodia since the reign of the Khmer Rouge. In fact, only 3 Cambodian archaeologists were left in the country after that brutal genocide. The physical and intellectual infrastructure of the country needed to be rebuilt.

Today, the situation is much better, with many young Cambodian archaeologists making collaborative archaeology a successful reality. But Cambodia’s past has created a unique situation for Alison and others.

“We walked around the village and everywhere on the surface we found ceramics dating back to the Angkorian period,” she relates. “But unlike the people in Angkor Wat, the villagers had no frame of reference to know who archaeologists are or what they do.” Prasat Baset is off the beaten path for tourism, too.

Thankfully, “there was a lot of interest from the local villagers in the history of the area,” Alison explains. “We hired a lot of the villagers to help us in our work, and they’ve been really welcoming.”

The way Alison and her collaborators do research makes for a successful and respectful endeavor for several other reasons:

- They work closely with Cambodian archaeologists and governing bodies. In Angkor, they work with the APSARA National Authority and in Battambang, they work with the Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts (the overarching government body that oversees all archaeology in Cambodia) as well as the Provincial Battambang Department of Culture office.

- They are completely open and transparent with the local people. “We explain what we’re doing to anyone who comes by,” Alison says, “and we have open archaeology tour days.”

- They respect the artifacts as the property of Cambodia. All the materials stay in Cambodia and if they need samples for radiocarbon dating or other study, they submit a request and obtain approval.

- They are innovative in how they engage the Cambodian people in order to share the results of their research. First, they write a report on each field season and post it online in English and Khmer. Second, noticing that Cambodians are very active on Facebook, they have presented live video on the platform and stay active to embrace an online social community. Third, they hired a Cambodian artist to create a comic book in the Khmer language, describing life in the Angkorian period. “It’s a cute story,” Alison relates, “there is a little girl whose dad works on the project; the archaeologist talks to her about what they’ve found, then she falls asleep and dreams about the Angkorian period.”

Preliminary sketches for Alison’s collaboration with Cambodian comic book artist, Lida Y. He has produced a separate comic book to help combat looting. Drawings courtesy of the artist.

All of these tactics help to remove the bad taste of having Westerners explore and remove Eastern cultural treasures in the colonial era. It is something about which Alison and her colleagues are very intentional.

Of course, cultural treasures still manage to be disturbed, looted, and destroyed. “There are artifacts everywhere,” Alison exclaims with an archaeologist’s touch of exasperation. “There is a lot of opportunistic looting, especially around infrastructure projects like road construction that uncover artifacts.” Alison has heard stories from the villagers in Prasat Baset that in the 1990s and 2000s, some people roved around the countryside with metal detectors. These treasure hunters would ask the villagers to scan their yards and pay them for anything they found.

What’s more, since Hindu and Buddhist cultures practice cremation more than burial, there is not the same sense of respect for the bones of the dead. Older, prehistoric burials that are found when plowing or digging are looted without much thought. “You could maybe make a year’s worth of salary selling what you found,” Alison says.

Alison Carter, PhD (left) with her Cambodian colleagues during their community archaeology day at Baset in 2022. Photo courtesy Alison Carter.

Increasingly, there are local heritage police and active department of culture offices trying to put a stop to looting. “I’m hoping that as more people learn about the archaeological record, they can help change the culture,” she states.

And that is precisely what Alison is doing with her research. She travels to Cambodia once a year to do 6-8 weeks of field work in May-July. Thanks to work like hers, the world is learning more about a fascinating medieval culture and the Cambodian ancestors of the Angkorians are able to preserve and maintain a vital link to their past.

To glimpse what life may have looked like for people in medieval Angkor, check out the interactive virtual experience created by researchers at the University of Monash, Australia.

Learn more about other speakers featured in the NHMU 2023 Lecture Series.

Michael Mozdy is the Associate Director for Science Communications in the Department of Radiology and Imaging Sciences at the University of Utah and a part-time contributor to the Natural History Museum of Utah. Our mission is to illuminate the natural world and the place of humans within it. In addition to housing outstanding exhibits for the public, NHMU is a research museum. Learn more.