Rachna Reddy's Quest to Understand Adolescent Primates and the Essence of Humanity

Note: Dr. Rachna Reddy spoke at the inaugural Women in Nature & Science celebration at NHMU on Saturday, February 10. She also spoke in advance of the opening of the Becoming Jane exhibition at NHMU.

By Mark Johnston

As Dr. Jane Goodall once said, “It’s very clear once you’ve spent time with the chimpanzees that you can no longer draw a sharp line between humans on the one hand and the rest of the animal kingdom on the other. It’s a very blurry line and it’s getting more blurry all the time.”

The blurring of that line continues today thanks to the work of other primatologists following in Goodall’s footsteps. For example, take a few minutes to talk to Dr. Rachna Reddy and her enthusiastic explanation of chimpanzee emotions will demonstrate just how much we humans have in common with our ancient ancestor.

Reddy is an anthropologist and primatologist at the University of Utah who has been studying chimpanzees in the wild since 2011. That might be a short decade compared to Goodall’s 60-plus-years career, but Reddy has already delivered new and fascinating insights into the lives of chimpanzees.

Just like Goodall, Reddy spent her childhood “obsessively” loving animals and following wildlife around her home. And while she would watch television programs on scientists like Goodall following animals in exotic locales, it was not something Reddy believed anyone could pursue for a career.

“They just seemed like they were in another universe,” she recalled.

Still, her passion for animals led Reddy to earn a bachelor’s degree in evolutionary anthropology from Duke University, where a pathway to researching primates began to emerge. First came work at the Duke Lemur Center and then an opportunity to spectate a research group where graduate students presented their work. Eventually, Reddy found a place on a study abroad program with the Organization for Tropical Studies that took her to South Africa to observe wildlife on the savannah.

“And then I got hooked,” said Reddy with a broad smile, before recalling the sadness she experienced once back on campus the following semester realizing how desperate she was to continue studying animals in the wild.

Her enthusiasm did not go unnoticed, and soon a research advisor connected Reddy with Cat Hobaiter, who was seeking research assistants to habituate a group of chimpanzees in Uganda. With this connection Reddy entered that other “universe” once accessible only on a television set, following the footsteps of Goodall closer than she ever imagined.

Image courtesy of Rachna Reddy.

On her early excursions to Ngogo in Kibale National Park, Uganda, Reddy would struggle through challenging terrain following wild chimpanzees and observing their behaviors, sometimes up to 13 hours a day for as long as 15 months straight. Like getting to know one’s human neighbors, proximity is key to truly understanding, so having the animals’ trust means everything. This is normally earned by habituating a community over a drawn-out period in which researchers immerse themselves in the chimpanzees’ environment as closely as they’re permitted, just as Goodall first did in the 1960s. It’s a big effort for the human observers often conducted by rotating teams, but once trust is earned, the up-close access makes it all worthwhile.

“You get plugged in really quickly because they’re so similar to humans and the ways they’re moving about the world are so similar. Like when they’re playing, they laugh; they’re ticklish especially on their armpits; they airplane babies; they might hold another’s hand and express fear when scared; when they eat something they really like they show joy,” says Reddy, energetically demonstrating the various emotions.

“You really get to experience life.”

"What it Means to be Human"

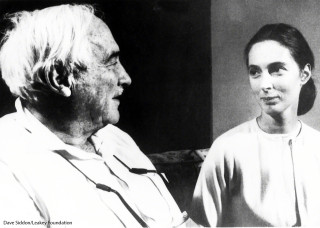

In 1960, Goodall’s first assignment in Gombe Stream Reserve in Tanzania was at the bequest of her mentor, Dr. Louis S.B. Leakey, a paleoanthropologist who studied human origins. As is said of Leakey, “He hoped that by learning about our past, we would gain a better understanding of what it means to be human.” That hope is still shared by researchers like Reddy, who in 2016 was a grantee of the Leaky Foundation for her study of "The development of male reproductive strategies in wild chimpanzees.”

Since Goodall first witnessed chimpanzees using tools, our understanding of their intellectual capabilities has grown immensely. They are capable of learning more than 400 signs used in American Sign Language, they are compassionate caretakers, they are part of complex social structures and can manipulate one another socially. As Goodall once expressed in a lecture:

They do each have their own vivid and unique personality, they also have emotions similar to those that we call happiness, sadness, fear, despair; they’re capable of both mental as well as physical suffering. And all of these things I just said were considered absolutely not possible when I first went to Cambridge University in England in 1961.

Goodall’s groundbreaking research has propelled us far beyond debating these evident truths and enabled researchers to delve deeper into the study of chimpanzees. Take Reddy’s research as an example, which aims to uncover an evolutionary basis for how and why social relationships shape human life. Like Goodall, Reddy uses longitudinal studies of chimpanzees as she examines how social relationships manifest, develop, and contribute to various aspects of life. In particular, she has been paying close attention to the development of adolescent chimpanzees and the positive and negative influences that shape their outcomes.

Adolescent Journeys

Like humans, chimpanzees’ identities change immensely during adolescence. It’s a time of great social development, when old bonds are broken, and new bonds develop. Chimpanzee adolescence begins between the ages of 8–11 years old, although this can vary from group to group. It marks the beginning of adulthood, a social designation determined by other adults, and the journey for male and female chimpanzees differs greatly.

As juveniles, male chimpanzees are almost always with their mother, their “anchor point” as Reddy calls it, except for occasions at play with other juveniles or doting adults. Then, between 8–12 years old, things start to change as the young males begin their climb through the community’s social structure.

At first, adult males withdraw their affection from adolescent males, which can appear distressing as the youngsters continue to seek their attention. Then, a year or two later, things get more aggressive when the adolescent males cross a boundary to become reproductive competitors while not yet alliance partners who can be relied upon.

Acceptance into the adult male social world can vary based on a group’s demographics and the cultural learning of the adolescents. At some sites, Reddy has noted chimpanzees reaching their early 20s before being accepted by regular coalition males, at other sites they are still in their teens. On average, it’s about a 10-year period of being ostracized, but once accepted they gain strong, affectionate bonds with fellow males.

Up until that point, “It’s almost like they’re getting hazed,” Reddy said.

The most intense bonds develop with participation in dangerous activities, like patrols, when bands of adult chimpanzees, both male and female, will explore the perimeter of their territory. When paths cross with chimpanzees from another community, it often leads to lethal inter-group aggression.

“But what’s happening during the patrol is highly affiliative, and it’s a bit haunting that what seems to bond them is related to this outgroup aggression and killing,” Reddy said, noting that adult females take part in these patrols, too.

Image courtesy of Rachna Reddy.

Like humans, a female’s journey through adolescence is very different.

During adolescent years, females sever bonds with the group into which they were born and seek out a new group never to return “home” again. This comes with significant risk as acceptance from a new group rarely comes easy. Some immigrant females are beaten badly and return to their mothers, only to try again later with renewed motivation.

It’s these attempts at acceptance that determine the female’s social status in the new group. That status will remain for life and will also determine where she can feed and how long her infants might survive. Eventually, that status will be inherited by her offspring. So, as you might imagine, females in the new community are eager to preserve their own standing.

“Imagine what you’re doing at 14 and how it will determine the social status of your kids when you’re 40,” Reddy said.

She also notes that while it’s common among mammals for one sex to disperse while the other stays behind to prevent inbreeding, from an evolutionary perspective it’s rare for it to be the females. Leaving "home" limits the benefits of staying in a familiar landscape with strong social support, which can improve chances of finding food and successfully raising young. So, this unique behavior of female chimpanzees is a mystery still worth exploring.

Image Courtesy of Rachna Reddy.

These and other observations of chimpanzee adolescents have revealed a lot of parallels with humans, like the duration of puberty, participation in risky behaviors to gain admiration status, the support of mothers to reduce the stress of growing sons, the value of dependable social relationships, and the desire for respect from seniors.

In studying these similarities, Reddy hopes to better understand mental health development patterns that shape mental health outcomes. If, say, the benefits of a mother’s support can be identified in young male chimpanzees, it might help us better understand the mental health outcomes of different parenting styles in humans. Or if we can better understand the ancient process of sexual dispersal among female chimpanzees, we might learn about our own innate urges to fly the coop!

Life Lessons

Throughout these years of fieldwork in Uganda, Reddy earned her Ph.D. in anthropology at the University of Michigan before conducting postdoctoral fellowships at Harvard University and Duke University. She is now an assistant professor in both anthropology and environmental and sustainability studies at the University of Utah. Her fieldwork in Uganda continues, and she recently started observing bonobos (humans other closest relative) who offer a whole new world of personalities.

Reddy's countless hours with primates are helping amass data that will support research for decades to come, but they're also altering how she observes day-to-day human behavior back home. Meeting a new baby in the family now takes on a whole new meaning as Reddy compares its response to the world to that of an infant chimpanzee. Even behaviors of the doting parents, she notes, are shared among chimpanzee mothers in the wild.

Reddy has also picked up valuable life advice from the chimpanzees, especially when it comes to the importance of maintaining close social and intergenerational ties.

“However your kinship structure works, maintaining relationships over time and fostering new ones among people you know is probably one of the best things we can do to continue to have peaceful interactions,” said Reddy, while also noting that chimpanzees can struggle with family reunions, too!