NHMU 50: The Museum's First Curator

By Riley Black

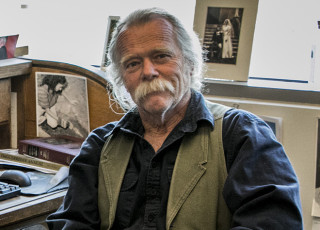

Natural history museums aren’t just the displays and exhibits. Behind the scenes, there’s a whole other world in which past discoveries are cared for and new ones are made. And key to these endeavors are museum curators, like the Natural History Museum of Utah’s first and still-working scientific curator Eric Rickart.

NHMU Curator of Vertebrate Zoology and Adjunct Associate Biology Professor at the University of Utah, Rickart cultivated his interest in natural history from an early age. His father’s work at Yale University led to early visits to the institution’s famous Peabody Museum of Natural History, and summers spent on his grandfather’s farm in the Midwest introduced Rickart to the wonders of the outdoors. “It was a combination of seeing a lot of places and, ultimately, being comfortable hiking and camping and being out of doors and at the same time being aware of the fact that there were places like museums where there were scientists who did work,” Rickart says.

But the critical moment came when he was 13. He met another young man who kept his own natural history collection at home and who had a father who worked as an entomologist at Yale. Zoology wasn’t just a hobby, but could be a career. “I thought ‘Man, this is for me. This is something I really want to do,'” Rickart says.

The path took Rickart to the University of Kansas. There he learned everything from cave ecology to the biogeography of mammals from professors like A. Byron Leonard, Robert E. Beer, and Robert S. Hoffman. But when it came to graduate work, Rickart followed the advice of his father to look elsewhere and expand his horizons. The search led him to the University of Utah, and, in time, to NHMU--then known as the Utah Museum of Natural History.

“The museum was a relatively small place, and it didn’t really even have any collections at that time,” Rickart says. For a budding zoologist, the sparse collection meant a lack of opportunity for research and other work. But after Rickart finished his PhD the biological specimens from the University of Utah were set to be transferred to the Museum, and he talked to Museum Director Don Hague about helping take care of the collection. “He hired me as a part-time curator, and that’s how I got started at the museum,” Rickart says.

Other people had helped collect and care for Museum specimens before, but Rickart became the first official scientific curator at the institution. Over the years, the position came to be a full-time endeavor. And it still is today.

Work in zoology involves many different skills, Rickart says, like figuring out how old records relate to collections. “A big project that I had was reorganizing the mammal collection and installing a bunch of material that had been received from the environmental labs at Dugway Proving Grounds,” he says, with the collection totaling several hundred bird and mammal specimens. Each of these specimens had to be identified and curated along with the existing collection, following evolutionary relationships to determine which specimen should go where.

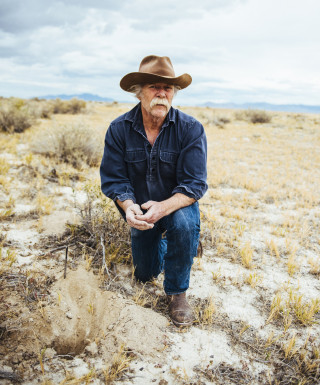

There are a lot of paperwork tasks, too. “You see errors in the data or specimen identifications, you correct them. You are on call when a scientist comes and wants to use the collection, somebody from outside or somebody from the department,” Rickart says. Then there’s fieldwork, writing papers and grants, and other work that helps the science keep running.

The increased space of the Museum's new home, the Rio Tinto Center, has been a huge benefit. “One of the things that changed is that we didn’t have the space limitations that we did before,” giving Rickert and colleagues enough room to make new collections and continue essential zoological research. Collections could be made and supplemented in regards to what the science required rather than what would fit in the old space.

These collections not only inform current research, but they connect people across time. “When you pick up a specimen that was prepared by somebody you never met because they died well before you were born, you can still feel a connection with them,” Rickart says. It’s not only a history of nature, but of people like Rickart who continue to share their fascination with the world we live in.

Riley Black is the author of Skeleton Keys, My Beloved Brontosaurus, Prehistoric Predators, and a science writer for the Natural History Museum of Utah, a part of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. Our mission is to illuminate the natural world and the place of humans within it. In addition to housing outstanding exhibits for the public, NHMU is a research museum. Learn more.