Lokiceratops rangiformis: A Horned Giant of the Cretaceous

Meet this New Dinosaur at NHMU

Paleontologist Mark Loewen will make a public presentation on Lokiceratops at NHMU at 1 p.m. on Saturday, June 29. The talk is included with admission.

Lokiceratops rangiformis is now on display for a limited time at the Natural History Museum of Utah. Book your visit today to meet this new discovery in person!

By Jude Coleman

Twelve million years before Triceratops roamed western North America, another horned giant stomped through the area’s Cretaceous marshes. It’s named Lokiceratops, and scientists just discovered that it’s a never-before seen species.

Lokiceratops rangiformis Illustration by Andrey Atuchin

Paleontologists found Lokiceratops’ skull in 2019, near the border of Montana and Canada. Scientists estimate the dinosaur lived around 78 million years ago, during the late Cretaceous period. After making a cast of the skull, researchers began putting it back together and comparing it to other similar dinosaurs. And that’s when they noticed something unusual.

“We started to realize that it was different than anything that anyone's ever seen before,” said Mark Loewen, a paleontologist at the Natural History Museum of Utah and University of Utah. “We've actually been able to reconstruct very well what the animal looked like.”

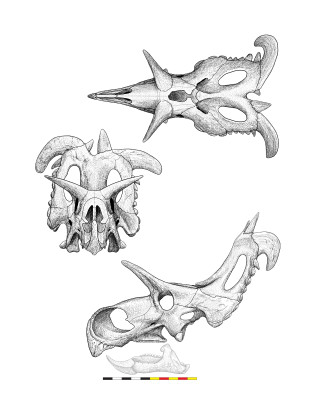

Lokiceratops belongs to a larger group of dinosaurs called ceratopsians, which are beaked, horned dinosaurs that eat plants. After ceratopsians, they’re part of a subgroup called centrosaurines, a cousin of the Triceratops. The two groups share many similarities, such as facial horns and huge head frills (the plate-like structure at the top of the skull). But they also have distinct differences. Centrosaurines were smaller — around the size of the elephant — and had a rounded nose instead of an elongated one.

Paleontologist Mark Loewen stands next to casts of the head and skull of Lokiceratops rangiformis. Photo by Mark Johnston / NHMU

Compared to other centrosaurines who lived alongside Lokiceratops, the new dinosaur had two large, paddle-like horns on the edge of its frills and several asymmetrical spikes in the middle of the frill. Along the sides of its frill, there was additional nub-like ornamentation. It also lacked nose horns, which was common among its evolutionary relatives. “Taking all this together, this represents a new species of dinosaur,” said Loewen.

The original fossil is housed at the Museum of Evolution in Maribo, Denmark, but a replica of the new dinosaur was unveiled today at the Natural History Museum of Utah. Researchers make replicas by creating a detailed mold of the fossil, and then filling that mold with a cast. The cast pieces are then put back together. The museum has an elaborate collection of dinosaurs, making it a frequent stop for paleontologists. One type of dinosaur NHMU is known for is horned dinosaurs, making this new addition particularly exciting, adds Loewen.

Its full name is Lokiceratops rangiformis. Lokiceraptops means “Loki’s horned face,” which pays homage to the Norse god of mischief by the same name. Rangiformis means “formed like a caribou,” and is a reference to the dinosaur’s asymmetrical frill paddles, which are similar to the mismatched antlers of a caribou or reindeer.

Lokiceratops lived alongside three other closely related species of centrosaurines, which is surprising, said Loewen. It’s unusual to have several species of the same type of large animal in one place — usually, different species inhabit separate locations.

Illustration by Sergey Krasovskiy

“When I started working on ceratopsians we would tell you, there's one of the round nose guys and one of the elongate nose guys in every ecosystem and never more than that,” he said. “No one would ever expect this.”

Such a diversity of similar animals living together at one time indicates that the centrosaurines underwent rapid evolution. That evolution was likely spurred on by mate preferences, called sexual selection. That means mates were repeatedly drawn to certain traits (in this case likely a detail of the frill) and, overtime, passed those traits down to more offspring.

The habitat that these horned dinosaurs lived in could have also contributed, because it was a relatively small area. What is now western North America was once just a sliver of land, an island continent called Laramidia. It stretched from modern-day Alaska down to Mexico, and across to western Montana through Texas. Laramidia started forming around 100 million years ago when Pangea was breaking apart. The Earth’s plates pushed away from each other rapidly, and in the case of Laramidia, caused the ocean to spill onto the land, forming islands. The species that lived on Laramidia became separated from the rest of North America.

Lokiceratops and its cousins lived only in the northern part of Laramidia, and Lokiceratops itself lived close to the eastern edge of the island. Although the area today is mostly grassland with a semi-arid climate, it was warm and humid during the Cretaceous period. The tropical landscape was awash with swamps, floodplains and lush greenery.

Lokiceratops rangiformis Illustration by Fabrisio Lavezzi

Loewen and colleagues wanted to know how these isolated ceratopsians — including Lokiceratops — fit into the overall picture of horned dinosaur evolution. To do that, they needed to recreate the horned dinosaurs’ phylogenetic tree. A phylogenetic tree is a way of representing how species are related and how they’ve evolved, where each species is a different “branch” connected to a main stem.

“We took every horned dinosaur that is known by decent material,” said Loewen. “We built a data matrix of thousands and thousands of characteristics across 80 different animals to come up with a new family tree of the entire group.” The origins of horned dinosaurs started back in the Jurassic period, when most horned dinosaurs were living in Asia. But a few found their way to North America, where they ultimately became isolated on Laramidia.

“They explode into this radiation of the two great families of ceratopsians,” he said. Those “two great families” were centrosaurines and chasmosaurines, the group that Triceratops is part of. “Lokiceratops falls right in the middle of this tree.”

Lokicepratops’ identification was borne from the work of a global team of scientists, funded by the National Science Foundation, the University of Utah, and the Museum of Evolution.

“It really was great to work with scientists from all over the world,” said Loewen.

See this dinosaur for a limited time at the Natural History Museum of Utah. Book your tickets today.