The Ecological Legacy of Bears Ears

By Beth Mitchell

Plant species richness at Bears Ears reveals archaeo-ecosystems, and implications for public land management

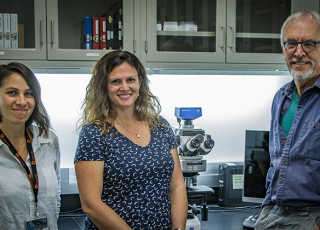

In a new study published on May 17, 2021 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), husband and wife team Dr. Bruce Pavlik and Dr. Lisbeth Louderback coined the term archaeo-ecosystem to describe what they and their collaborators and coauthors found while surveying Bears Ears—and why Indigenous co-management is essential for protecting and restoring its ecological legacy.

“Bears Ears is not just about boundaries, it's about management,” said the study’s lead author Bruce Pavlik, director of conservation at Red Butte Garden. “And it's not just about artifacts. It's also about the archaeo-ecosystems that have persisted through the ages. That's what's sacred to Native people.”

“Our ancestors tended to these ancient gardens that warrant a special management regime,” said co-author Cynthia Wilson, director of the Traditional Foods Program for Utah Diné Bikéyah and member of the Navajo (Diné) Nation. “Right now, there’s no real security to prevent damage.”

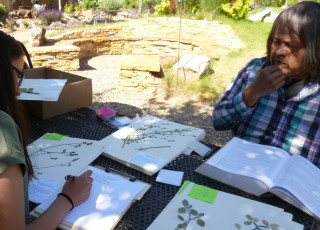

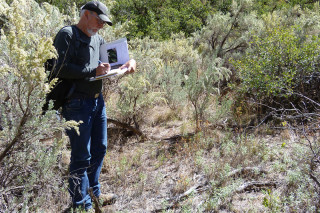

The authors surveyed 25 archaeological sites in the Bears Ears region, and collected plant specimens found at those sites, focusing on those used for food, medicinal, ceremonial and utilitarian purposes by the Hopi Tribe, Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, Apache Tribe, Pueblo of Zuni and the Navajo (Diné) Nation who trace ancestry to or currently reside in the region.

What they found was that sites with dense archaeological features, indicative of larger populations of people, also had a higher diversity of these culturally significant plant species. Their findings confirm that archaeo-ecosystems have stories to tell, and that Indigenous knowledge and collaboration is critical to protect these cultural living landscapes.

Co-author Arnold Clifford, renowned botanist at Carrizo Mountain Environmental & Herbarium, Inc., and member of the Navajo (Diné) Nation, noted that some of the documented plant species, such as sagebrush and pinyon pine, are common across the Bears Ears landscape. However, at least 31 plant species associated with these archeological sites are otherwise extremely rare, including the Four Corners potato (Solanum jamesii), a native tuber-producing species that is an important medicine and food source. It is one of seven of these plant species held sacred as ‘lifeway medicines’ that occur in the vicinity of habitation structures.

According to Dr. Pavlik, this indicates that the plants weren’t just randomly growing there; rather, they were introduced to the landscape by earlier cultures. “This is one of the rare times in the archaeological literature where people invested in native species and brought them to their habitations,” Pavlik said. “It indicates this higher level of landscape manipulation, what we call an ecological legacy of past human occupation.”

Using data on known archaeological sites from Utah's State Historic Preservation Office, co-author Brian Codding, anthropologist and director of the University of Utah Archaeological Center, worked with anthropology Ph.D. students Peter Yaworsky and Kenneth B. Vernon to develop a statistical model assessing botanical richness based on archaeological and environmental variables for an additional 240 archaeological sites across the Bears Ears region.

"We used what we recorded in the field to project our findings across the whole region," Codding said. "The model can help Tribal and federal land managers identify places that need the most protection to preserve complex archaeological sites and important plant species."

Effective stewardship of the Bears Ears region will require special management policies applied to these botanically and culturally rich archaeo-ecosystems. A blend of western science and deep Indigenous ecological knowledge can be used to mitigate the effects of increased visitation, proposed development and expanded resource extraction.

“What Tribal members have said all along is that you don't just preserve the archeological site,” said Lisbeth Louderback, curator of archaeology and director of the archaeobotany lab at the Natural History Museum of Utah and anthropologist at the University of Utah. “You have to preserve the entire resource space around the site, including the plants. Building a management plan incorporating both western science and traditional knowledge will get a full picture of the best way to take care of the resources and the monument.”

Beth Mitchell is Senior Manager of External Communications at the Natural History Museum of Utah, a part of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. Our mission is to illuminate the natural world and the place of humans within it. In addition to housing outstanding exhibits for the public, NHMU is a research museum.