The State Fossil of Utah: Allosaurus fragilis

By Jude Coleman

Long before Tyrannosaurus rex reigned supreme, another intimidating predator ruled in the area that is now Utah — Allosaurus fragilis. Paleontologists have found more Allosaurus fossils in Utah than anywhere else on Earth. It’s so prevalent, in fact, that it holds a special honor in the state.

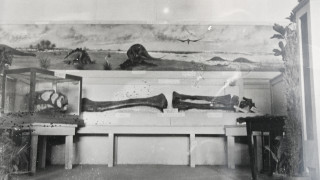

Allosaurus fragilis on display at the Natural History Museum of Utah. Photo by Mark Johnston

“Not only is it a cool dinosaur, but it's the official state fossil of Utah,” said Randy Irmis, the Curator of Paleontology at the Natural History Museum of Utah and a professor of geology and geophysics at the University of Utah. He said Allosaurus’ abundance has given scientists an unprecedented opportunity to learn about these ancient dinosaurs and their lifestyle.

It was one of the biggest predators around during its time in the Late Jurassic Period, approximately 150 million years ago. At 15 feet tall and nearly 30 feet long, it was about the size of three grizzly bears stacked atop each other — with a long tail that made up nearly half its body length. The meat-eating giant also had three-fingered hands adorned with half-foot long claws, which were ideal for grasping its unfortunate prey.

“Not an animal you’d want to run into in a dark alley,” Irmis said. He emphasized that although Allosaurus fragilis is the state fossil, it’s not the state dinosaur — that honor goes to the Utahraptor.

Allosaurus belongs to a group of dinosaurs called theropods: two-legged, three-toed animals, such as Utahraptor and T. rex. Theropods ultimately evolved into birds, making the fearsome Allosaurus an ancient relative of pigeons and backyard chickens.

Although it was similar in size and geographic range to T. rex, Allosaurus lived in a completely different environment, and more than 80 million years before its relative. During the Late Jurassic, North America was part of a massive supercontinent called Laurasia. What is now the Pacific Ocean began roughly near the modern-day Nevada-California border. Much of Utah and the surrounding areas were floodplains, with broad, open areas dotted by forests. It was a warm, humid place with wet-dry seasons. There were no flowering plants — those wouldn’t evolve until several million years later. Instead, conifers and ferns made up the majority of plants. During this time, sediments were deposited in layers that would eventually erode away to form Utah’s red, grey, and green badland layers spread around the eastern portion of the state. red rocks, arches, and canyons.

Of the plethora of Allosaurus fossils uncovered across Utah, most of them came from a site called the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry. Paleontologists have unearthed thousands of bones — totaling around 50 different Allosaurus individuals — from Cleveland-Lloyd, located in the middle of the state. It’s part of the recently established Jurassic National Monument.

Past Worlds

Want to learn more about Allosaurus and Utah's dinosaur past? Plan a visit to Past Worlds at NHMU, a breathtaking exhibition all about Utah's dinosaurs.

“The majority of [Allosaurus] bones excavated from this site are cared for in our collection at the Museum, and some are on display,” Irmis said. Cleveland-Lloyd dates back to the early 1900s, when the first excavations began. Most of the digs took place in the mid-to-late 1900s conducted by University of Utah paleontologists.

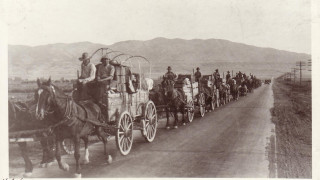

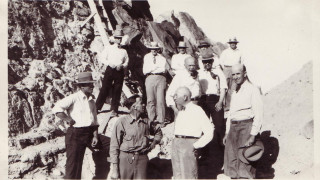

Another site home to Allosaurus remains is Dinosaur National Monument, which straddles the northeastern border of Utah and northwestern Colorado. Discovered in 1909, this site is home to the “Carnegie Quarry” — a rich dinosaur quarry preserving ten different species of dinosaurs, which was excavated by the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburg, PA, from 1909-1922. The University of Utah excavated 80,000 pounds of fossils at the Carnegie Quarry in 1924, and one of the more complete specimens found included a nearly complete Allosaurus. A replica of this skeleton is featured in an exhibit at the Salt Lake City International Airport. You can still visit the historic Carnegie Quarry today at Dinosaur National Monument, and experience the “Wall of Bones” preserving these fossils in the original rock where they were first discovered.

1 of 14

Thanks to the extensive fossil record in Utah, scientists have learned a great deal about dinosaurs in the area, including Allosaurus. Because there are so many individuals to compare to, researchers can make better guesses about what was the norm for these animals. For example, scientists know that Allosaurus tended to “live fast and die young,” Irmis explained. They only lived to be around 25 years old, reaching their adulthood between 18-20 years old. In some bones, scientists have found signs of illness, such as infections or healed breaks. And although Allosaurus looked starkly different from modern-day birds, researchers have even been able to piece together some of their bird-like behavior. For instance, it seems based on the evidence from Cleveland-Lloyd that these dinosaurs would come together socially, at least at some point in their lives.

“Allosaurus is really iconic for Utah,” Irmis said.

To see Allosaurus on display at the Museum, head to the Past World exhibition. Irmis also encourages those that can to visit Dinosaur National Monument, where visitors can see excavated fossils as well as those still in the ground at the Monument’s famous quarry wall.

1 of 3

“Utah is famous for its fossil heritage, and particularly its dinosaurs,” Irmis said. “What better place to introduce visitors to the state of Utah to the amazing fossils we have than with an Allosaurus skeleton in the airport.”

Utah’s dinosaur legacy is possible because of a perfect storm of sediment deposits and mountain formation. In order for fossils to form, an animal or plant needs to die and come to rest in sediment. Sediment is the muddy, silty, or sandy material that settles at the bottom of a body of water, such as a lake, river, or ocean, or is blown in by wind (such as sand dunes). Because Utah was covered in floodplains and rivers — during most of the time of the dinosaurs (Mesozoic Era), ample sediment was deposited in the area. Over millions of years, thousands of feet of that sediment built up in layers, along with all the organisms that perished in it.

Around 66 million years ago as the Cretaceous Period came to an end (that’s around the time the non-avian dinosaurs went extinct) a combination of uplift began to form the massive mountain ranges that exist in Utah today. As erosion accelerated over the last 30 million years or so, the dinosaur-era layers of rock became exposed. That means not only were many dinosaurs preserved, they were also later revealed.

This article was posted in celebration of the unveiling of an Allosaurus fragilis fossil display at the Salt Lake City International Airport. The display, featuring a fossil from NHMU's paleontology collection, was made possible by generous support from the Lawrence T. & Janet T. Dee Foundation, Kirk Ririe, and Bob and Cyndi Douglass.

Dinosaur National Monument

See the discovery site of the Airport Allosaurus at Dinosaur National Monument.