Diné Artist and Utah Veteran Connect Through Storytelling

By Olivia Barney

Authentic storytelling brings people together in a profound way, and it’s an art form that has been respected across cultural groups and historical eras. Some early groups of people recorded their histories in pictographs and hieroglyphics, while others passed information on through oral tradition. As language and technology have evolved across the world, people have continued to connect through the stories expressed in art forms like poetry, paintings, and podcasts (to name just a few).

George Sumner and Rosabelle Shepherd at NHMU Mark Johnston

The Navajo people tell their stories in a variety of ways, including ceremonial performances, woven art, and oral expression. They also create storyteller bracelets, which depict an individual’s journey and way of life through the use of symbols. Visitors of the Natural History Museum of Utah’s annual Indigenous Art Market might recognize this style of jewelry as one of the many expressions of Indigenous art that’s been displayed and sold at the market. But these bracelets, like other forms of storytelling, do more than communicate information — they also create connections.

One of these unexpected connections began in 2023, when George Sumner, a veteran of the Vietnam War, was first introduced to Diné artist Rosabelle Shepherd. Though their backgrounds and life experiences were different, they established a meaningful, unexpected connection through the programs and exhibitions at NHMU.

A Family Legacy: Five Generations of Diné Silversmiths

Rosabelle Shepherd is a Diné artist from Arizona whose family carries a legacy of artistic expression. Her late father, Donald, was known among their people as “Little Silversmith,” as he was a fourth-generation silversmith who created jewelry, hatbands, and horse bridles. Shepherd's earliest memories of her father’s work come from when she was just four years old. Donald sat cross-legged on the dirt floor of their family Hooghan (traditional dwelling of the Navajo people), hammering molten silver, carefully inspecting his work, and soldering silver pieces together. Shepherd can recall the delighted faces of her father’s customers, as well as the emphasis he placed on carrying on the traditions, culture, and language of their ancestors. He taught them that materials from the earth, like silver and turquoise, were sacred, so they had an obligation to prepare for their silversmithing work through prayer and good thoughts.

Sumner's custom storyteller bracelet. Mark Johnston

Shepherd’s five brothers began silversmithing at a very young age and became masters by their teenage years. In adulthood, her brothers encouraged her to embrace the family business. She had been around it her entire life, the skill was in her blood, and her brothers were eager for her to believe in herself.

Then, when Shepherd was in her late thirties, and had worked in public health for 14 years, she decided she needed a change in life. She recalled the encouragement of her brothers and father, believing for the first time that she might be capable of excelling in the family trade. Shepherd is now a fifth-generation silversmith and the first female in the family to embrace that legacy.

I create every piece of jewelry with the teachings and stories of our culture, traditions, and prayers. All my work is connected to my father. Every piece is done in his remembrance with love and admiration.

Shepherd is currently in her 26th year of silversmithing and has made a name for herself. Her jewelry is meticulously crafted with a tremendous amount of thought and consideration — particularly for custom commissions.

Utah Veteran's Uniform Displayed at the Smithsonian

Sumner is a Utah-raised, farm boy who got drafted into the U.S. Army in 1966 — at the height of the Vietnam War. He trained as a helicopter pilot and served two one-year tours in Vietnam, flying in and out of combat zones for days on end: transporting both supplies and fallen service members.

His return to the states was met with resistance. Anti-war protestors filled streets, airports, and college campuses; so, upon arriving home, veterans were encouraged to discard their uniforms to avoid conflict with these groups. Most followed that advice, trading in their uniforms for civvies (civilian clothes), but Sumner opted to keep his uniform — hiding it at the bottom of his bag and leaving the military base dressed like a civilian.

Those first few weeks home challenged Sumner in new ways. Across the United States, he watched protestors unite in criticism against the U.S. presence in Vietnam. He heard of an incident at Kent State University, where the National Guard fired into a crowd of anti-war protesters, killing four. Sumner began to question the ethics of his country, and therefore himself.

If the war was wrong, did that mean he was wrong?

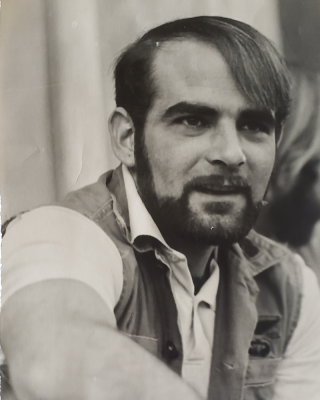

Young George Sumner wearing Army vest. George Sumner

By the time he returned to college in the fall of 1970, Sumner felt numb, confused, and hollow. He kept his head down whenever he passed the rallies on campus, and his Army uniform remained at home, hidden from public view.

One day, Sumner heard the leader of a protest on campus declare that because war was wrong, Vietnam veterans and active service members should be considered war criminals. This condemnation immediately sparked shock and anger in Sumner, which was a welcome change after so many months of confusion and emptiness.

Sumner had to make a change. He began wearing his buttoned-down Army shirt everywhere he went — to school, the movies, and social events. This quiet declaration of his military service sent a signal to other veterans in the area, and soon, Sumner belonged to a community of peers who, like him, had both felt the honor of serving their country and witnessed the senseless brutality war brought. Together, they began marching in protests of their own — Veterans Against War — which allowed them to recognize the patriotic sacrifice they’d made while still working to prevent others from having to endure the haunting experiences they had faced in battle. Their uniforms became living declarations of their beliefs, and Sumner wore his so often, that he eventually had to cut off the worn sleeves and wear it as a vest.

Years later, when the Vietnam Veterans Memorial opened in Washington D.C, veterans and the family members of fallen soldiers began leaving uniforms or other memorabilia at the base of the wall. Though he couldn’t attend the initial opening with his friends, Sumner eventually made the trip to D.C. and reverently left his shirt at the memorial site.

Fast forward to 1992, and Sumner is once again in Washington D.C. — this time with his wife Tina. They toured the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, exploring an exhibition that showcased artifacts left at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. Tina was looking at a nearby case of Purple Heart awards, but Sumner was transfixed on a sight so shocking, he audibly gasped.

“That’s my shirt,” he said.

Tina thought George meant he once wore a similar uniform. Sumner shook his head; he wasn’t being metaphorical. There, on that worn-out, sleeveless Army shirt, were his jump wings, pilot wings, and faded name: Sumner.

Storytelling, Storyteller Bracelets, and an NHMU Connection

A few years ago, Sumner joined a team of storytellers on The Moth, a radio show that features real stories from everyday people. Its unique storytelling platform was created with the intention “to honor and celebrate the diversity and commonality of human experience.”

Sumner’s story promoted that goal: highlighting the emotions and experiences that help us discover our identity and make us human. In his new role as storyteller, Sumner traveled the world, telling his story to nearly 20 of The Moth’s live audiences. These speaking tours also connected him with other groups, including various veterans’ organizations, who invited him to speak at their events.

Front view of custom storyteller bracelet. George Sumner

When Sumner first learned about Navajo storyteller bracelets, he felt a pull toward the tradition and longed to have one of his own. But he also knew the sacred nature of these bracelets for the Navajo people, and he wanted to be conscious of cultural appropriation or any action that might disrespect a culture that he found so much beauty in.

This thoughtful approach led him to seek out an Indigenous artist from whom he could commission the piece — but who could he trust to illustrate the complexity of his story, one that was heavy with war, injustice, and loneliness? Not every Indigenous artist would be willing to take that on.

As a Salt Lake City resident, Sumner attended a former special exhibition on Navajo basket weaving at the Natural History Museum of Utah. It was at this exhibition, Weaving a Revolution, that Sumner met Suzanne Ruhlman, the manager of NHMU’s Museum Store and founder of the Museum’s annual Indigenous Art Market. After sharing his story (and goal of commissioning a custom storyteller bracelet), Ruhlman put Sumner in contact with Shepherd.

Side view of custom storyteller bracelet. George Sumner

They met in person at the 2023 Indigenous Art Market, where Shepherd agreed to tell Sumner’s story through her art. While both parties expected the project to be completed within a few weeks, it was a full year before they next met.

Sumner is not of Navajo descent, but in his request, he trusted Shepherd to decide on the jewelry’s content and design. This would be the first time she created a storytelling bracelet for someone outside of her cultural heritage, and she wanted to be thoughtful in her approach.

She researched for a long time before deciding on the right symbols to include on Sumner’s bracelet. Most of these symbols were easily recognizable because they were representative of his life. But Shepherd also included a few symbols unique to her own Navajo community.

Side view of custom storyteller bracelet. George Sumner

Many Indigenous groups have sacred ceremonies and traditions for the physical, spiritual, and emotional healing of their people — particularly those who have seen battle or death. The Navajo people avoid speaking of death, striving to balance living within the Hózhó (beauty and goodness). They believe that the spirits of the slain can attach themselves to those who were present at their deaths, so these healing ceremonies were meant to cleanse them, lest that heaviness affect their minds, bodies, or spirits. By incorporating symbols from Navajo healing ceremonies into the custom design, Shepherd bestowed a blessing, protection, and prayer to help Sumner “walk in beauty” despite the death he’d seen through his service.

The two storytellers reunited at NHMU’s 2024 Indigenous Art Market, where Shepherd presented Sumner with the finished bracelet. Both parties were emotional at the exchange, and Sumner recalled weeping for days afterward in awe and gratitude.

The bracelet’s artistic perfection, and its blessings of beauty, renewal, and strength, filled me with a tearful spirit — like a lost and exhausted traveler finding home.

After their paths crossed at the Museum, Shepherd shared her family legacy and cultural heritage a veteran and new admirer; Sumner created an authentic connection with respect and reverence for a culture beyond his own; and NHMU was the thread that tied their inspiring stories together.

Visit NHMU's Indigenous Art Market

Since 2013, NHMU has hosted an annual Indigenous Art Market that attracts some of the country’s most talented Native American artists to Salt Lake City. More than 25 tribes have been represented over the years, bringing a wonderful diversity of traditional and contemporary Native American art that is available for purchase. Visitors can shop one-of-a-kind jewelry, pottery, sculptures, paintings, beadwork, weavings, and much more—all while learning about tribal traditions from artists working to preserve them. Every year, 100 percent of sales from NHMU's Indigenous Art Market go directly to the artists.

NHMU's annual Indigenous Art Market is included with museum admission, which is free for Museum Members.