Studying the Ecological Disturbance of Lakes in the Colombian Andes

By Jude Coleman

Nestled in the Magdalena valley of the Colombian Andes, a lake holds secrets of its basin’s history. Formed within the caldera of an exploded volcano, the lake — called Laguna de San Diego — has lived through bouts of climate change, human settlement, and war. Susana Velasquez-Franco wants to see those changes through the lake’s eyes. Or rather, its sediment.

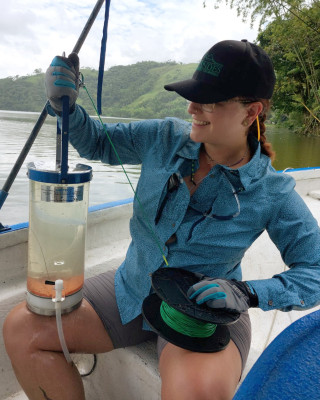

Susana sampling water at various depths in San Diego Lake to assess its physical, chemical, and limnological characteristics.

Velasquez-Franco, a first generation paleoecologist at the University of Utah, is piecing together a story of ecological disturbance in the area that took place over the last 1,000 years. To do that, she’s using sediment cores from San Diego lake, which contain clues such as heavy metals, charcoal, pollen and microscopic animals.

While working on a NSF archaeology project several years ago, she became interested in what lake records existed in Colombia, where she spent most of her life. But she couldn’t find any. She hopes her work will fill knowledge gaps about climate change and human influences in the area.

“I realized that we have very few records, or lakes, that feed that kind of middle elevation in the mountains of the Andes,” she said.

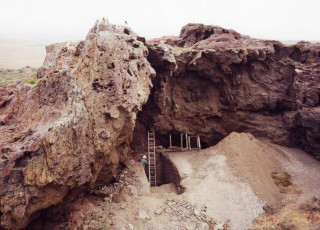

San Diego Lake during a browning event (2022-2023), showing murky water indicative of the lake's changing conditions.

San Diego is one of only two of those crater lakes in the north of South America, both of which sit between roughly 2,300 to 3,300 feet in elevation. The other lake, El Tabor, also holds important data that Velasquez-Franco is studying in its silty dregs. Using a long, tube-like tool, she collects chunks of sediment from the lakes and dates each layer to determine how long ago the sediment was deposited. What she finds within those layers then helps to create a snapshot of the ecosystem throughout time.

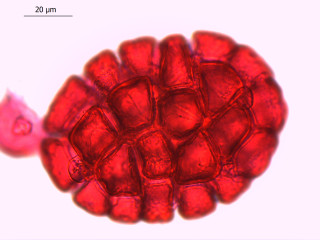

Pollen grains from Albizia carbonaria, a native South American tree species, locally known as Carbonero. This tree belongs to the Fabaceae family, commonly referred to as the bean family.

For example, one sediment component she looks for is charcoal, which reflects the fire history of the lakes’ basin, providing clues about wildfires and human settlement. Similarly, pollen grains reveal information about what trees and plants surrounded the lake throughout history — giving researchers an idea of how species have shifted over time. Sometimes, those shifts are a result of climatic changes that Velasquez-Franco can also detect in the lake cores, such as droughts or ice ages. Titanium, aluminum, and iron levels, for instance, all provide information about rainfall patterns that change during those events.

Cattle and buffalo ranching have been expanding in the region following the 2013 and 2016 peace agreements, supported by international cooperation agencies. However, these efforts often overlook the impact on local biodiversity and the resilience of the lake ecosystem.

But ecological disturbance can result from human influence too. For most of the last millennium, San Diego lake was surrounded by neotropical rainforest. Today, it is flanked by a patchwork of pastureland, where trees were clearcut for buffalo and cattle grazing. With the increase of agricultural activity, the rare lake has started to change from an emerald green to a murky brown — possibly a result of fertilizer runoff.

In addition to the surrounding environment, the cores contain signs of how the lake itself has changed as well. Levels of carbon and nitrogen indicate how much living matter the lake contained, a measure that ecologists call productivity. Highly productive ecosystems churn out biomass in the form of plants and animals, which decompose and leave their carbon and nitrogen behind in the muck. “Everything that happened around the lake is recorded in the lake mud,” Velasquez-Franco said. “These lakes are all the time acting kind of like remote sensors of the landscape.”

When she says everything, she means it: Even signals of war are buried beneath the surface. For the last 250 years, the region around San Diego lake has been caught in the crosshairs of conflict. Despite the area’s isolation, Velasquez-Franco said, there were territorial disputes between military and guerrilla groups. Evidence of that conflict remains in the sediment in the form of heavy metals, such as lead from bullets. In the mid-to late-1900's, that warfare displaced communities near the lake for several decades. After the Colombian government signed several peace agreements in 2013 and 2016, locals began to return.

Beyond Sediment

The first-ever frozen core taken from San Diego Lake in 2020 by Velasquez-Franco and Mitch Power revealed a rare varve record, providing valuable insights into the lake’s past climate and environmental changes.

Sediment cores aren’t the only data that Velasquez-Franco collects from the area. She’s also working to compile a biodiversity baseline for the San Diego lake basin, so that there is a record for scientists to compare to in the future — particularly as climate change continues to alter the environment. “Wildfires and all those disturbances are happening with more frequency with climate change,” she said.

The tropical Andes are known as a biodiversity hotspot, rich in species unique to that area. Around San Diego lake, for example, there are over 160 species of trees. But those numbers have been dropping as people return to the lake, Velasquez-Franco said. In addition to plants, other life forms she keeps track of are diatoms: a type of single-celled algae with cell walls made of glass. So far, she’s found seven new species of the organisms. Diatoms are very sensitive to changes in water quality, making them valuable sentinels for detecting changing conditions.

Finally, she combines her survey and core data with satellite imaging of the area. Those images help explain how the landscape has changed in recent years.

“I’ve been doing a lot,” Velasquez-Franco chuckled. “As a native Colombian, I also like to engage the community with the research itself and work with them.”

The additional outreach is important, because although part of San Diego lake is protected, the safeguards in place aren’t as strong as they could be, she said. By sharing her research with community members — such as teachers, ecotourism organizations, and local land owners — she has the opportunity to talk about broader conservation topics. In particular, she likes to educate locals about invasive plants and the importance of preserving soils.

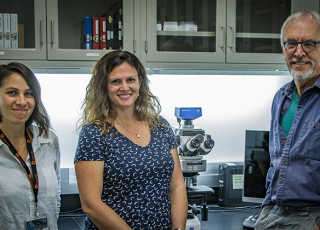

NHMU Researchers Susana Velasquez-Franco, left, and Mitchell Power, Ph.D., right, unbox collected sediment cores from their Colombian field campaign. The boxes they were transported in were made from their research raft, now disassembled, while collecting data on lakes in the field with limited resources. Photo by Jack Rodgers / NHMU