Prehistoric Penguins Help Research March On

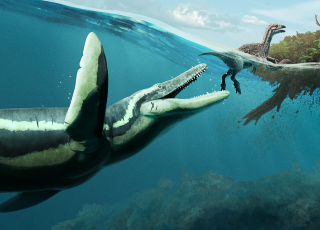

This article was published in advance of DinoFest, an event which took place at NHMU on January 25 and 26, 2025. The event explored ancient underwater worlds and marine reptiles.

By Olivia Barney

When it comes to animals of the prehistoric, our thoughts often turn to the large, roaming reptiles known as dinosaurs. We’re fascinated by them — displaying their fossilized bones and footprints in museums and creating film franchises focused on their ferocity. But not all prehistoric animals were fierce giants and not all of them were dinosaurs.

Though we tend to use the term quite generally, “dinosaurs” applies only to a specific group of prehistoric animals that share certain traits. Of course, every rule has its exceptions, so there’s a bit of ambiguity around how to properly categorize a dinosaur. The most general definition describes a dinosaur as an extinct creature with upright limbs that lived during the Mesozoic era (roughly 252 to 66 million years ago). Not every expert agrees on this definition though, so the exact criteria might change a bit depending on who you talk to.

But regardless of how you look at it, one truth is universally agreed upon: not all prehistoric animals were scary, ferocious reptiles. In fact, some were the ancestors of the clumsy, black-and-white birds we know and love — penguins.

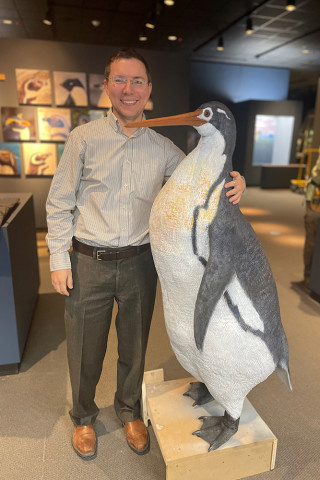

Daniel Ksepka, Ph.D., discovered his love for prehistoric birds mostly by accident. His lifelong love for dinosaurs motivated him to pursue a doctorate in paleontology, but it was while there that his interests narrowed in on ancient avians. Ksepka's proximity to prehistoric birds at the American Museum of Natural History gave him a view of paleontology that he hadn't seen before, and before long, he had shifted his focus from dinosaurs to penguins.

Studying prehistoric penguins has its benefits: in addition to an extensive and impressive fossil record, we have access to an abundance of living penguins that provide helpful comparative metrics for researchers. Not all branches of paleontology are as lucky — after all, we don't have a close, living comparison to aid in researching dinosaurs like Allosaurus fragilis. An abundance of penguins (living and extinct) makes it a bit easier to trace the evolutionary changes of penguins throughout history.

Studying ancient penguin life has other perks too. As the species traded the sky for the sea, their bones changed in density. They no longer needed light, hollow bones required for flight — and denser bones (especially those that eventually fall into the sediment on the ocean floor) have a greater chance of fossilization. This means that compared to other prehistoric life, and certainly compared to prehistoric birds of the air, there are significantly more penguin specimens that have been fossilized and preserved.

The more Ksepka learned about ancient avians, the more interested he became. Soon, he found himself excavating fossils on warm coastlines, collecting data from live penguins, and working alongside some of the greatest minds in the industry. As Ksepka narrowed his field of interest to prehistoric penguins, he quickly realized that with such an extensive and well-preserved fossil record, he could potentially answer some big evolutionary questions. Ksepka currently works as a curator for the Bruce Museum, but he continues to travel around the world, studying penguins (living and extinct) and searching to answer one of his biggest questions.

When Did Penguins Transition to the Sea?

The short answer is that we don’t yet know for sure, though Ksepka believes there’s evidence to indicate that the change happened around 66 million years ago — right around the time a massive meteor struck the earth and wiped out most prehistoric life. To date, no fossil records have been found of penguins older than 62 million years. This means we have no fossils from penguins that had the ability to fly, but through the study of related prehistoric birds (like the albatross), we know they likely once flew through the air — perhaps occasionally diving toward the water for a fishy snack.

Giving up flight sounds like a bad thing, but it was the best thing to happen to penguins.

A lot of factors have to align for flight to take place: a bird can’t be too heavy, its bones can’t be too dense, and its feathers have to be shaped just right to catch the wind. When penguins gave up flight, they no longer had to worry about these requirements. Their feathers became stiff and sleek, their bones became denser to help them stay underwater, and they could pack on as much muscle as they needed. After such a large mass extinction, there were fewer predators to fear and less competition over food. Perhaps this is why, shortly after taking to the water, enormous two-hundred-pound penguins emerge, leaving behind a fascinating fossil record that paleontologists, like Ksepka, are still learning from.

Kairuku: The Diver Who Returns With Food

Ksepka will be one of two keynote speakers at DinoFest: Underwater Worlds, which takes place January 25-26, 2025. During the weekend’s festivities, Ksepka will be taking guests on a deep dive through prehistoric waters and answering questions about ancient birds, including penguins!

Ahead of his visit, we asked Ksepka if he had a favorite penguin species (modern or prehistoric). His answer was both immediate and enthusiastic: Kairuku.

The name Kairuku comes from the Māori language, loosely translating to “diver who returns with food.” There are currently three Kairuku species: Kairuku waitaki, Kairuku grebneffi, and Kairuku waewaeroa. These 27 million-year-old birds would have been a striking sight — slender, with an elongated trunk, narrow bill, and long wing bones that made them look almost regal. They were tall too — standing about 4 feet 2 inches (more than a foot taller than modern emperor penguins).

The first Kairuku specimen was discovered in New Zealand in the 1940s, but it wasn't immediately identified as a new species — there simply weren’t enough fossils in that original finding to determine what they were looking at. Over the decades, however, more complete specimens were recovered by Ewan Fordyce, Ph.D., a brilliant expert who worked with and mentored Ksepka for many years before his passing in 2023. It was Fordyce who discovered a stunning set of orange bones set in green sedimentary rock that would become the holotype for the Kairuku species. A holotype is the specimen that all other specimens of that species are compared to, making it a crucial part of the research process.

Fossilized skeletons of the three Kairuku species are among the most complete of all the ancient penguins, making them a fascinating study in prehistoric penguin history. Over the years, Ksepka spent many years in New Zealand, joining Fordyce in additional Kairuku excavations and gaining his friendship and respect in return. It was these efforts, along with Fordyce's guidance in New Zealand, that solidified Kairuku’s place as "favorite extinct penguin" in Ksepka’s heart.

You can learn more about Kairuku, and other areas of Ksepka's research into ancient avian life, by attending his lecture Diving Into the World of Fossil Penguins on Sunday, January 26, 2025.

About Daniel Ksepka, Ph.D.

Daniel Ksepka, Ph.D., serves as Curator at the Bruce Museum. His research focuses on the phylogenetic relationships and evolution of wing-propelled diving in penguins. Ksepka also contributes to the study of avian brain evolution and the paleoecology of the giant bony-toothed Pelagornithidae. He enjoys sharing natural history discoveries through exhibitions at the Bruce Museum and writing for American Scientist and Scientific American.