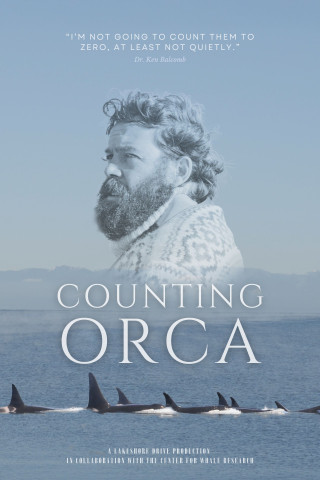

Counting Orca

Related Event Alert

This article was published in advance of the Counting Orca premiere on April 5, 2025.

By Jude Coleman

Off the jagged coastline of northern Washington, one of the world’s longest marine mammal studies is taking place. It is Orca Survey: a research project focused on Southern Resident orca whales. The study is based out of San Juan Island, in the southern Salish Sea archipelago. For nearly 50 years, researchers have monitored the Southern Residents and their dwindling population size. What was once a thriving community some hundreds-strong is now a struggling group of around 70.

In 1976, marine biologist Dr. Ken Balcomb started the Orca Survey after learning how orca populations had been destroyed in recent years. Between the 1960s and mid-1970s, a frenzy of captures for aquatic parks slashed whale numbers by the hundreds — visitors can learn more about this in NHMU's current special exhibition, Orcas: Our Shared Future.

Orca Survey relies on photo identification methods to track individual whales through time, allowing researchers to keep tabs on the whales’ numbers and their condition. This research, and the orcas, became a significant part of Balcomb’s life's work. He spent over four decades surveying the whales every year, eventually founding the Center for Whale Research on San Juan Island in 1984.

“He saw something special in Southern Residents, and through his work with that, people saw something really special in Ken, too,” said Natalie Taylor, a filmmaker in Salt Lake City. Taylor was once the volunteer coordinator at the Natural History Museum of Utah, but has since moved on to founding a film production company with her two sisters. Their debut film is about Balcomb, who passed away in 2022, and the Center for Whale Research. A premiere of “Counting Orca” will be held at NHMU on April 5.

The legacy of multi-generational research that Balcomb left behind is vital for understanding this long-lived species, said Darren Croft, the Executive Director of the Center for Whale Research. Croft is also a professor of animal behavior at the University of Exeter. Orcas can live up to 100 years, so a single animal’s entire life can’t be observed by one generation of scientists alone. The whales hit sexual maturity at around 10 years old, and, similar to humans, enter menopause around 40. Menopause is exceptionally rare in mammals — only humans and a small handful of whale species experience it. Orcas’ unique family structure may help explain why this unusual trait has evolved.

“They have this amazing post-reproductive life where mothers and grandmothers are helping their offspring and grand-offspring,” said Croft. “The old matriarchs act as repositories for knowledge.”

Each family group, called a matriline, is centered around the oldest female, trailed by her sons and daughters, and her daughters’ offspring. These tightly-bonded family groups can reach sizes of nearly twenty. Several related matrilines together form a pod.

Image courtesy of the Center for Whale Research

The Southern Residents are a community of just three pods, totaling 73 whales. It was Balcomb’s research that first alerted wildlife managers that there were far fewer orcas in the population than had been estimated, prompting policy change regarding their capture. Not all orca whale populations are at risk, but the Southern Residents are critically endangered. A major contribution to their plight is lack of food. During the summer months Southern Residents rely almost entirely on chinook salmon, an animal facing its own threats. For example, dams in salmon habitats have prevented many fish from accessing prime spawning sites in historically important rivers. Other factors including rising temperatures, fishing pressure and habitat degradation are also taking a toll.

“The orca population really balances on a knife-edge at risk of extinction,” said Croft. “There are not enough of those large, big, fatty salmon that they would have had access to historically.”

Image courtesy of the Center for Whale Research.

Every year, all Southern Residents return to the Salish Sea to feast on migrating salmon, and historically, they would have stayed there for most of the summer. That’s how they earned their title of “residents.” That also is why researchers at the Center for Whale Research can catalogue and observe the same whales year after year. In recent years however they have been less resident as they need to travel further afield to find food

It starts with a whale sighting, said Michael Weiss, the Research Director at the Center. He and a crew embark in a small aluminum boat to track down the whales. Sometimes they’re right off the island, and other times they have to travel for several hours to reach a pod. Once they catch up to a group, their first goal is to take photos of whales’ dorsal fins and the white splash just behind it, called a saddle patch. Each whale has unique markings in those areas that the researchers can use to identify them, such old cuts in their dorsal fins.

The team also collects behavioral information from drones, with an aim to understand what contributes to whales’ survival and reproductive success. “There’s still a lot we don’t know,” said Weiss. By observing the same group of whales for many decades, the researchers hope to answer some of the questions that remain. “We're hoping for 100 years of Orca Survey so that we can really say that we've seen the full lifespan of one of these animals.”

If the Southern Residents are lost, it will be the first population of animals to go extinct where researchers know every single member, said Taylor. That’s a detail that stood out to her in her research, she said, particularly because she had only recently learned about the group of orcas. She originally discovered them in a book, and, after doing more research, came across Balcomb’s work at the Center for Whale Research. She hopes the film will give viewers an opportunity to sit with what it means for an animal to go extinct—but also that it will remind them of the importance of community and coming together to spark change. “There's a lot of power in community able to make positive change...and Ken really embodies what that looks like,” said Taylor.

Interested in learning more about orca and the work of Dr. Ken Balcomb and the Center for Whale Research? Join us at NHMU on April 5 for the premiere of the short film "Counting Orca."

Orcas: Our Shared Future

Learn more about orcas in NHMU's current special exhibition open through April 20, 2025.