Uncovering the Ocean's Secrets with Susan Casey

This article was published in advance of the 2025 NHMU Lecture Series, featuring Susan Casey and other experts. Reserve free tickets here.

By Jude Coleman

Susan Casey has been to the underworld. It was watery and dark, with intense pressure and little warmth. It’s the deep sea: a vast stretch of ocean that begins around 200 meters below the surface. It reaches depths of nearly 11,000 meters, and it’s barely been explored.

“There’s this massive universe down there,” said Casey, an author who focuses on ocean stories. On March 24, she will open NHMU’s 2025 Lecture Series with a free talk at the Museum entitled “Uncovering the Ocean’s Secrets,” which she’ll present again the following day at the Viridian Event Center in West Jordan. “It’s so vast we can’t really wrap our heads around it.”

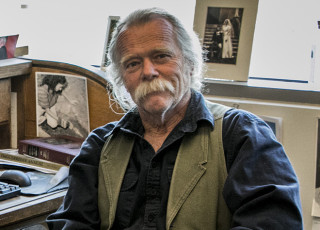

Photo by Rennio Maifredi

Casey, who is based in New York and Hawaii, has visited the deep sea three times in submersible vehicles. Each dive took her to different depths, and featured their own unique, remarkable sights. Or lack of sights, in the case of her deepest dive to 5,200 meters. Those depths are called the abyssal zone, the habitat ranging from 3,000 to 6,500 meters below the surface. To journey so deep, said Casey, submersibles must be incredibly sturdy, built only of materials that can withstand four tons of pressure per square inch. That meant there were only a few small windows to view her surroundings through –– and the surroundings were difficult to see regardless. The area is pitch black, illuminated only by the vehicle’s spotlights and the occasional glowing creature.

“You absolutely realize where you are, the pressures that are surrounding you, and the gravitas of being in the deep,” she said. “It's very spiritual. You just can't get out of a dive like that and think of the world in the same way.”

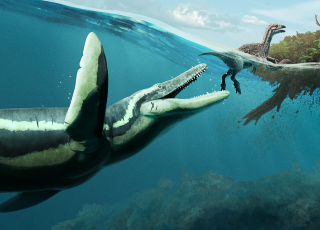

The abyssal zone, combined with the even deeper hadal zone and two shallower zones (the midnight and twilight zones), make up 95 percent of the Earth’s habitat. Some reports estimate we’ve mapped less than a quarter of it. Scientists have also barely scratched the surface of the organisms living there. In addition to being home to hundreds of thousands of species, the deep sea is also an important part of the planet’s carbon cycle. That cycle starts with tiny photosynthetic organisms called phytoplankton, which absorb carbon dioxide as they photosynthesize. Each night, a wave of creatures from the twilight zone—600 to 1,000 meters below the surface—rises to shallower depths to eat these plankton, then swims back down to the deep. By doing this, these tiny fish and other organisms shuttle carbon from the atmosphere into the depths, where it can remain sequestered for centuries, or even millennia.

The deep ocean’s out-of-sight, out-of-mind remoteness and its spooky reputation are two reasons why Casey strives to emotionally connect people to the subject. Her latest book, “The Underworld,” aims to do that by illustrating for readers the deep’s interconnected tapestry of life. The first time she got a glimpse of that tapestry was while studying great white sharks off the Farallon Islands nearly two decades ago. The extreme, dark waters yielded no warning about what lurked beneath the waves. One moment, an 18-foot shark could surface, the next, a blue whale. “That's what really got me intrigued, was that anything could pop up,” said Casey. “What is down there? And nobody really knew.” So began her foray into the world of the deep. It took seven years to research “The Underworld,” she said, including her three submersible dives.

Another one of her dives took her through the twilight zone, the deep ocean’s uppermost layer. It was markedly different from her trip to the hadal zone. For starters, the submersible’s pressure hull—the spherical capsule that keeps passengers safe under pressure—wasn’t a thick metal shell. Instead, it was made of foot-thick plexiglass, which meant she could see the ocean in all directions. And there was much more to see. As she and the crew dropped through the water, hundreds of bioluminescent creatures glowed around them.

“It's like you're floating in a crystalline bubble...falling through a rain of fireworks,” she recalled.

There are more organisms in the twilight zone than all the other regions of the ocean combined, and the majority of them can put on a light show. They include things like ctenophores, a kind of gelatinous, blobby invertebrate; siphonophores, a long, thin organism reminiscent of a wet feather boa; and squids that glow with what looks like dozens of stars. Bioluminescence happens due to a chemical reaction inside an organism's body. Scientists think that the lights send a message to other creatures––such as attracting mates and prey, or warding off predators.

Casey has also visited a hydrothermal vent during a dive. Hydrothermal vents are cracks in the seafloor where water mingles with magma. They’re piping hot and filled with toxic chemicals. Remarkably, an astonishing array of life still prevails there –– animals that survive by chemosynthesis, energy from the earth’s interior, rather than photosynthesis from the sun. Hydrothermal vents also draw the attention of another crowd: people interested in deep-sea mining. The vents, as well as the rest of the seafloor, contain valuable metal deposits.

In recent years, scientists have spoken up about the dangers of mining the seafloor. In particular, they argue that not enough is known about the ecosystem to make an educated assessment of what damage mining could cause. By damaging the sea floor ecosystem, we would be ultimately harming the rest of the planet in reckless ways, said Casey, given its oxygen-generating and carbon-sequestering capabilities. Mining isn’t the only threat the ocean faces, either. Climate change and pollution are both taking their toll, warming and acidifying the planet’s waters while fouling it with trash and chemicals.

It’s another reminder of our connectedness to the sea. Not only is the ocean the cornerstone of cycles that impact humans, but humans' actions also impact the ocean. “We're part of this beautiful fabric of life that's bigger than we are,” said Casey. “We do have to act. But not all is lost.”

Hear from Casey when she opens the 2025 NHMU Lecture Series on March 24 at NHMU, when she presents Uncovering the Ocean’s Secrets and hosts a book signing. Casey will give the same lecture the following night at the Viridian Event Center in West Jordan. Tickets are free but seats are limited, and RSVP is required.