Weaving a Revolution: Contemporary Navajo Baskets

Mary Holiday Black weaving a basket, p.140 from the book "Weaving a Revolution." © NHMU.

By Michael Mozdy

Museums chronicle the material culture of civilizations: pottery, architecture, household goods, and more. Museums also celebrate incredible artistic and cultural achievement, from antiquity to the present. The Natural History Museum of Utah (NHMU) is fortunate to be the home for a collection of Navajo baskets that embodies both of these ideas: a contemporary art movement and new cultural achievement that is rooted in the form and techniques of ages-old ceremonial objects used by Navajos on a daily basis.

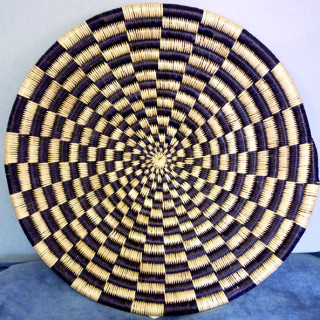

The woven ceremonial basket, or ts’aa’, comprises a formal form, color scheme, and design. Sometimes known as the wedding basket, it is a highly symbolic, highly prized sacred object used frequently by medicine men and families alike. Its white, black and red design and slight bump where the coil ends help to orient cardinal directions; it also tells the story of the harmony and balance between all living creations.

In a remote part of the Navajo Nation in southeastern Utah, a community known as Douglas Mesa became the unlikely epicenter for an artistic revolution.

Navajo artists in Douglas Mesa like Mary Holiday Black felt the pull of their own artistic sense as well as the interests of those who purchased their baskets. Mary Black was one of the first of several Navajo families to bring these influences into her weaving, slowly modifying the designs woven into her baskets, the colors used, and even their shape and scale. These changes found a ready market from buyers, and traders of Navajo art encouraged this artistic expression. The work of these few Douglas Mesa weavers led to an artistic explosion of ceremonial baskets that continues to this day.

NHMU is honored to house The Twin Rocks Trading Post Collection, a collection of 250 remarkable baskets from the Utah Strip of the Navajo Nation, some of which are on display in our Native Voices gallery and Collections Wall. The story and stunning photographic catalogue of these baskets has been published in the book Weaving a Revolution: A Celebration of Contemporary Navajo Baskets (available at the NHMU Gift Shop).

Becky Menlove, NHMU’s Associate Director for the Visitor Experience, notes that bringing the Twin Rocks collection to NHMU was a highly collaborative experience aimed at understanding and contextualizing the importance of the baskets. “During the making of the exhibit, we began with oral histories from many of the weavers,” she details, “and we later made exhibit-quality videos highlighting the weavers and their stories. We also consulted with an advisory group that included Clarenda Begay, the curator of the Navajo Nation Museum, some of the basket weavers, and several other basket scholars, including Carol Edison.”

This collection is important to protect for generations to come, and its truly revolutionary nature cannot be overstated.

From Ceremonial Basket to Story Basket

In the mid-1900s, the tradition of weaving ts’aa’ seemed to be nearly dead. By the 1970s, traders in southern Utah and northern Arizona occasionally received baskets made with depicted animals and human figures from the Ute and Paiute tribes – these were made for the tourist market. Yet the basket weaving tradition was alive and well with the Navajo families of isolated Douglas Mesa. In the 1970s, Mary Holiday Black in particular began experimenting with the technical aspects of the art by using local plants to make vegetable dyes and making more rarely seen jug-shaped baskets in miniature and oversize. Mary was an accomplished rug weaver, and she began incorporating geometric rug designs into her ts’aa’. Others in her community did the same.

The major breakthrough came, however, when Mary incorporated sacred images and designs, just as rug weavers had decades earlier. “Mary and her eldest daughter Sally were likely the first to include in their baskets representations of the Yé’ii – those sacred beings sent by the gods to help and heal the People and keep balance in the world,” claims Carol Edison, who served for 33 years as state folklorist at the Utah Folk Arts Program.

This was a major break with the traditional design of ts’aa’, and it marked the start of an entirely new basket style.

The symbolism inherent in traditional ceremonial basket design helps to ensure balance within ceremonies and in the people performing them. The white center is said to portray Mother Earth; the white break in the design emanating from the center to the white rim is the pathway of the Navajo people to this world and acts as an entrance for sacred powers and beings to come and go. Changing this design represents a potential disruption to community and individual balance.

Using fixed representations of the Yé’ii was a step too far for many Navajo medicine men, who opposed this imagery on baskets. But for Mary, the move to incorporate Yé’ii was part of a broader enterprise of storytelling. “There are many basket stories;” asserts Mary, “if we stop making the baskets, we lose the stories” (translated from Navajo).

And so, the Blacks persisted, trying to avoid any bad consequences by regularly participating in ceremonies designed to maintain balance with their surroundings. This began a new basket style that has become known as the Story Basket.

Carol Edison shares another story of how storytelling acts as a powerful force for preserving Navajo culture. The owners of Twin Rocks Trading Post in Bluff, Utah, remember a time when Mary brought in a basket that depicted the Fire Dance, an all-night Navajo ceremony that had not been performed regularly for many years but was originally part of the lengthy nine-day Hail Chant. With its alternating images of dancers and flaming sagebrush lighting their way, Mary’s basket preserved images from an almost-extinct Navajo ceremony, making them available to everyone.

The Simpsons at Twin Rocks and other traders responded eagerly to the emerging story baskets, and creativity flourished among the Navajo weavers. Sally Black actively sought to bring the emerging art form to museums and art shows across the country.

See Part II of our blog series on these amazing baskets: A Renaissance in Navajo Basket Art.

Michael Mozdy is a Digital Science Writer for the Natural History Museum of Utah, a part of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. Our mission is to illuminate the natural world and the place of humans within it. In addition to housing outstanding exhibits for the public, NHMU is a research museum. Learn more.

Many thanks to Becky Menlove, Lisa Thompson, and Tim Lee for their work in developing the exhibits to display the Twin Rocks collection, creating their gorgeous "Weaving a Revolution" book, and helping with the content of this blog post.