The Birth of the Antiquities Act

Bears Ears National Monument. Photo by Mark Johnston/markjohnstonphoto.com

By Westin Porter

“Have you ever spread your blankets on the warm sands of the southwestern plateau and stretched out your weary body in full relaxation?... Have you ever then filled your lungs with God’s pure mountain ozone and gazed up through that clear atmosphere into the heavens spread out above you where a million dancing, sparkling suns seemed to be nodding assent to your reveries and encouraging your happiness? If you have not, then your time has not yet come. You are not yet fit to die.”

-Byron Cummings, 1908

There are a thousand stories on display at the Natural History Museum of Utah. Beyond those displayed, in boxes and folders, collection cabinets and cases, there are yet thousands more. Tucked away in NHMU’s anthropology collection are boxes of photos, black and white, relic’d with age, and folders of archived field notes. The above passage comes from some such notes, beautifully composed by Byron Cummings, a former University of Utah Professor of Anthropology, while on one of his many expeditions to the American Southwest.

Byron Cummings' field notes © NHMU.

It is an inspiring scene to imagine—Cummings, sprawled underneath the ever-unfurling desert sky, the scent of sage and sumac hanging on the night’s breeze as he takes in some ancient panorama glowing before him. But contrary to what the reverent beauty of the Southwestern landscape might suggest, the scene Cummings looked upon that night was the centerpiece of national debate; over land, the people and antiquities within it, and how it should be dealt with as the American Frontier closed.

As settlers made their way across the continent, they scoured for water, arable land, and other natural resources to sustain their new way of life on the frontier. The further west they travelled the more Indian country they occupied and antiquities of those Native American civilizations began to surface as commodities, discovered by settlers and sold to institutions across the country (even the world) or to private collectors.

People like Richard Wetherill, the Colorado rancher who led several of Cummings’ expeditions, found they could make more money excavating sites like Betatakin and Keet Seel and selling found artifacts than they could farming. Pioneers of the nascent science of anthropology maligned them, called them “pot hunters,” a slight to denigrate their means of subsistence. While the practice was certainly questionable, it was uncharted territory.

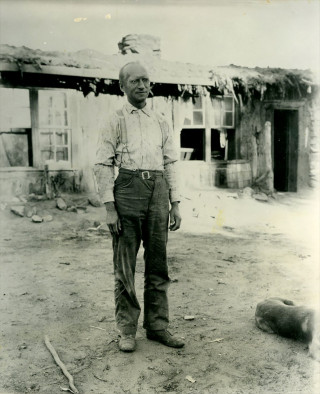

Byron Cummings © NHMU.

Anthropology was a relatively new field, and the distinction between accredited researcher and amateur explorer was fuzzy. While explorers like Wetherill claimed personal profit to the antiquities they sold, researchers like Cummings benefitted from discovering them and having them relocated to their respective institutions like the Field Museum, American Museum of Natural History, and the Utah Museum of Anthropology (a predecessor to NHMU).

As American settlement continued to expand westward contention mounted around how land and antiquities found on it should be regulated, if at all. Settlers and explorers like Wetherill drove the narrative that government attempts to regulate excavations of sites like Keet Seel, a thousand-year-old cliff dwelling in the Four Corners region, was federal infringement, both on state rights as well as the promise of individual economic prosperity in the form of land ownership for those westward bound settlers. For those groups of anthropologists and archeologists, the narrative was that these sites and the antiquities found within them should be protected for research and made available to the public through museums and nationally designated historical sites for public interest.

Kayenta Anasazi pottery discovered at what is now Navajo National Monument by Byron Cummings. Photo © NHMU.

“What is needed is a general enactment, empowering the President to set apart, as national parks, all tracts of public land which… is desirable to protect and utilize in the interest of the public,” wrote William A. Richards, the General Land Office Commissioner, to Secretary of the Interior, Ethan Hitchcock, in 1904.

Very near the turn of the 20th century, this debate came to a head. In 1906 Congress passed the American Antiquites act which was then signed into law by President Roosevelt. The Act authorized the President of the United States to designate land owned or controlled by the U.S. government as national monuments under two conditions: 1) that the monumentalized land be of “historic or scientific interest,” and 2) “That the examinations, excavations, and gatherings are undertaken for the benefit of reputable museums, universities, colleges, or other recognized scientific or educational institutions, with a view to increasing the knowledge of such objects, and that the gatherings shall be made for permanent preservation in public museums.”

While the lawmakers who created the Act had the American Southwest, a hotbed for unregulated excavation at the time, at the forefront of their minds, presidents have exercised it for more than a century to create national monuments around the country. NHMU anthropological and paleontological collections include thousands of objects from a variety of areas in Utah protected by the Antiquities Act. These objects are the foundation of important, ongoing research conducted by scientists in the last century, giving us a deeper understanding of past cultures and expanding our scientific knowledge of organisms from millions of years ago. Those objects and specimens, as well as so many majestic panoramas like those described by Cummings, are still here to be enjoyed today thanks to the American Antiquities act of 1906.

“If you really want to be lifted out of yourself and freed from the petty perplexities of life for a time, take a trip through the mountains and valleys and across the lofty mesas of Utah.” —Byron Cummings, 1908

Bears Ears National Monument. Photo by Mark Johnston/markjohnstonphoto.com

Note: This blog post was informed by the following sources: Byron Cummings Field Notes; America’s National Monuments: The Politics of Preservation, Hal K. Rothman; “The Great Race to ‘Discover’ Rainbow Natural Bridge in 1909,” Stephen C. Jett; “National Monuments to National Parks: The Use of the Antiquities act of 1906,” Robert W. Righter; “Ruins, Reputations, and Regulation: Byron Cummings, William B. Douglass, John Wetherill, and the Summer of 1909,” Hal Rothman.

Westin Porter is a Digital Science Writer for the Natural History Museum of Utah, a part of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. Our mission is to illuminate the natural world and the place of humans within it. In addition to housing outstanding exhibits for the public, NHMU is a research museum. Learn more.