How a Museum Artist Made a Firefly Glow

A Museum guest reads a panel on the News From Our Scientists exhibition at NHMU. Photo ©NHMU

By Riley Black

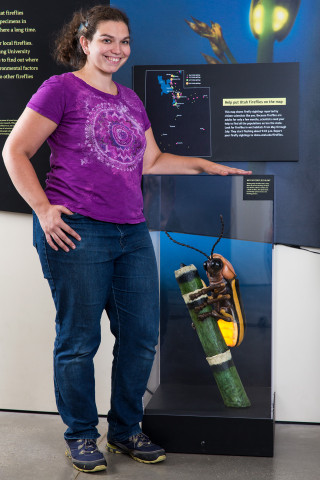

Utah evenings put on a spectacular light show, the setting sun throwing gorgeous hues across the mountains, meadows, and our Great Salt Lake. But, the distant star isn’t the only brilliant thing about the Beehive State twilight. Fireflies often come out to glow their messages after the sun goes down, and, to underscore that these charming arthropods really do exist here, Emily Szalay, a preparator with the Natural History Museum of Utah, has made a super-sized version of a lightning bug.

Fireflies, as museum entomology collections manager Christy Bills will no doubt tell you, absolutely have a home in Utah. Both males and females of our local species flash their bioluminescent lights to advertise to potential mates, inadvertently entertaining us, as well. There’s even a citizen science project meant to track where these insects hover and glow. Still, many have been surprised to learn that fireflies call Utah home. To give the insects a signal boost, Szalay created a larger-than-life version for the museum.

A real firefly is made out of lots of biological materials, like a shell made out of chitin. Constructing a giant facsimile from scratch required different materials. “The base is carved foam with a two-part epoxy skin,” Szalay says, with brass tubing making up the armature of the legs and antennae. And, when the exhibits team decided to put the insect on a horsetail to better show off its glowing abdomen, Szalay fashioned the plant out of cardboard and epoxy with the insect’s feet sculpted in place to give it a firm hold.

Bringing the beetle to life was a challenge. “I’m more of a 2D artist,” Szalay says, adding “There were a couple times when I had to completely scrap what I was doing and start over.” The epoxy, in particular, presented a steep learning curve. “It’s super sticky when you first mix it up and has the consistency of peanut butter,” Szalay says, although the right combination of moisture on protective gloves and a thickening powder made the substance easier to handle.

Then came the painting, which Szalay wanted to get just right. Thankfully, the museum’s own collection had good reference material for Szalay to narrow the palette. “I had to use a magnifying glass to really see the details on the real bugs,” she says.

In the end, though, Szalay wrangled all the goop, brass, and paint into a magnified version of what you might see as you wander around Utah this summer. Behind each of those little glowing lights is a beetle showing off to the world, bringing just that much more color to our desert nights.

Riley Black is the author of My Beloved Brontosaurus, Prehistoric Predators, and a science writer for the Natural History Museum of Utah, a part of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. Our mission is to illuminate the natural world and the place of humans within it. In addition to housing outstanding exhibits for the public, NHMU is a research museum. Learn more.