Rare Fossil Comb Jellies Uncovered in Utah's West Desert

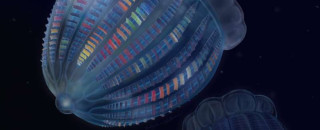

An illustration of comb jellies floating in an ancient sea that once covered Utah. Credit: Holly Sullivan

by Riley Black

Comb jellies aren’t the sort of creatures you expect to find in Utah’s west desert. Today, these soft-bodied animals – also known as ctenophores – live in oceans worldwide, from the surface to the deep. But comb jellies also have a fossil record that goes back hundreds of millions of years, a grand evolutionary tale that connects to the arid Cambrian rocks of western Utah.

Even though British Columbia’s Burgess Shale may be the most famous Cambrian fossil site on the planet, well known for remnants of early animals preserved in delicate detail, the rocks of Utah’s House Range are brimming with fossils that are just as spectacular. These rocks, dating back to between 520 and 500 million years ago, entomb what’s left of ancient reefs that were absolutely teeming with life. Among the creatures that swam, flapped, and floated through these waters were early comb jellies, although they were unlike any ctenophores alive today.

Described by University of Oxford paleontologist Luke Parry and colleagues Javier Ortega-Hernandez and Rudy Lerosey-Aubril in iScience, the comb jelly fossils might initially look like dark smears on the rock. But under close investigation with electronic microscopes, the paleontologists were able to find traces of the original internal anatomy inside the comb jellies. In fact, the researchers realized, the comb jelly fossils represent two new species – Ctenorhabdotus campanelliformis and Thalassostaphylos elegans. Trying saying that ten times fast.

What’s truly stunning about the ctenophore fossils is that they offer some clues as to how these strange animals sensed their environment. A Thalassostaphylos fossil, for example, preserves two tiny features called “polar fields” which are thought to help comb jellies sense their environment. A specimen of Ctenorhabdotus, on the other hand, has longed nerves that connect with the ring of the jelly’s mouth. This is different than modern comb jellies, whose nerves are like a more diffuse net. In some ways, the ancient comb jellies of over 500 million years ago had more complex nervous systems than their living counterparts.

The finds highlight the importance of the fossil record. If all we knew of comb jellies came from living animals, biologists would have no idea that the nervous systems of these animals changed so dramatically over time and were actually once more complex. The fossil record helps set the essential context for understanding how organisms have evolved and adapted through time, sometimes running counter to what we might expect. More than that, the finds help demonstrate that Utah’s fossil record truly is full of wonders. On the surface, something as squishy as a comb jelly would seem to have little chance of preservation. Yet, thanks to sheer luck, some of these creatures became part of the Earth’s rock record and allow us to envision what life was like back when western Utah was under a shallow sea.

Riley Black is the author of Skeleton Keys, My Beloved Brontosaurus, Prehistoric Predators, and a science writer for the Natural History Museum of Utah, a part of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. Our mission is to illuminate the natural world and the place of humans within it. In addition to housing outstanding exhibits for the public, NHMU is a research museum. Learn more.