Archaeological Evidence Suggests Men and Women Have Different Responses to Climate Change

Two Hadza grandmothers cooking Vigna frutescens (Hadzane: //ekwa) at a collection site. Small child waits to receive a share once cooking is finished. Image recorded dry season 1985, northern Tanzania. ©JF O’Connell

By Lisbeth A. Louderback

The recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) publication reports that women are more vulnerable to the effects of climate change due to their domestic responsibilities in the household and local community (Mbow et al. in press). In many rural areas and developing nations around the world, women grow crops for household consumption as well as storing, processing, and preparing the food. This means that when drought and aridity occur and subsequently impact food supply, women are more affected because of these gendered tasks.

This scenario is evident in our deep past as well. In a new paper that was published in American Antiquity, Dr. Lisbeth Louderback found that after 9,800 years ago, when climatic conditions on the Colorado Plateau were much warmer and drier than today, women’s foraging strategies shifted to exploit low-risk plant foods (such as small seeds and tubers) near their camps. Men, however, continued traveling far to hunt for high-risk large game, despite the effects of climate change. Dr. Louderback interprets this as a shift in gender division of labor. The reasons for this shift are the same today as in the past; women tend to be more responsible for the daily task of gathering reliable foods to feed their young and are, therefore, more likely to feel the effects of climate change than men.

Dr. Louderback began this investigation by examining how and why human diets changed over the past 11,000 years at North Creek Shelter (NCS), the oldest archaeological site in southern Utah. She analyzed animal bones and plant remains, along with stone tools, to test the prediction that increasing aridity caused the decline of high-quality food resources (e.g. large mammals) and, consequently, an incorporation of low-quality foods (e.g. small seeds) in the diets of the occupants at NCS.

Location of North Creek Shelter (NCS) in Escalante on the Colorado Plateau in southern Utah (indicated by yellow star). Inset map shows the physiographic boundaries of the Great Basin (green) and Colorado Plateau (orange), and the yellow star is the approximate location of NCS. ©NHMU/Credit Lisbeth Louderback

Results of this analysis showed that the remains of large mammals did not decline in abundance, but that small seeds and tubers, along with grinding tools, were increasingly used as aridity increased. So, what explains this difference in dietary patterns? Dr. Louderback suggests these patterns reflect different foraging strategies of men and women in the face of climate change.

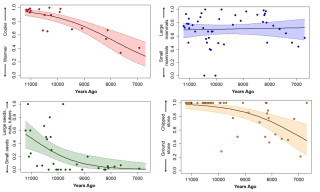

Climate, mammal, plant, and stone tool datasets from North Creek Shelter plotted against time. Over time, climate got warmer, small seeds were consumed more, and grinding stones (used to process small seeds) increased in abundance. But large mammals did not decrease in abundance despite climatic changes. ©NHMU/Credit Lisbeth Louderback

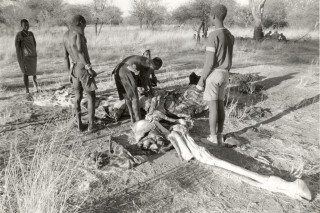

Modern hunter-gatherer groups, such as the Hadza in northern Tanzania, serve as evolutionary models that explain the origin of sexual division of labor. And although those origins are still debated, recent research suggests that division of labor may have originated with Neanderthals, over 100,000 years ago. This research is based on evidence that Neanderthals gathered a variety of plant foods and did not focus solely on large game, thus suggesting they had a social structure in favor of dividing labor for resource procurement (Henry et al. 2014).

This evidence, viewed alongside what Dr. Louderback documented at NCS, makes it clear that division of labor goes way back in our evolutionary past. The distinct responses of men and women were an advantageous set of behaviors because it increased the fitness and potential success of the group. These remnant patterns of gender roles still play out in rural areas and in developing nations where women are differentially affected by climate change.

Hadza men butchering a giraffe near Lake Eyasi, Northern Tanzania. Image recorded September 1988. ©JF O’Connell

Lisbeth Louderback is Curator of Archaeology at the Natural History Museum of Utah and Assistant Professor of Anthropology at the University of Utah. NHMU is a part of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. Our mission is to illuminate the natural world and the place of humans within it. In addition to housing outstanding exhibits for the public, NHMU is a research museum. Learn more.

References:

Mbow, C., C. et al., In Press: Food Security. In: Climate Change and Land: an IPCC special report on

climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems [P.R. Shukla, et al., (eds.)].

Henry, A.G., Brooks, A.S., Piperno, D.R., 2014. Plant foods and the dietary ecology of Neanderthals and early modern humans. Journal of Human Evolution 69, 44–54.

Louderback, L.A., 2021. Climate-driven Dietary Change on the Colorado Plateau, USA, and Implications for Gender-Specific Foraging Patterns. American Antiquity, 1-17.