A Fuzzy Invader—Fox Squirrels in Utah

Squirrel Fest is back! Whether you're a casual observer of backyard wildlife, or you're a seasoned zoologist, we want your help tracking sightings of fox squirrels in Utah. Submit your sightings during Squirrel Fest, happening December 7–15, 2024. Learn more.

By Westin Porter

Along the reedy shores of the Jordan River, bikers whir along a meandering path; along the surface of the slow water, ducks chug leisurely; and on the branches and down the trunks of the Cottonwoods that line the river, fox squirrels hop casually along.

While fox squirrels (Sciurus niger) blend into the valley landscape as well as their coats blend with tree bark, they are not native to Utah. In fact, they did not live in Utah at all until roughly seven years ago, when they were first spotted, here, along the Jordan River.

If there were an index that ranked the cuteness and fuzziness of Utah mammals, Fox squirrels would rank highly on it. They are longer and plumper than Utah-native squirrels, with a coat that washes from a creamy underbelly into a grey-brown speckle along their back, and nutmeg red at the fringes.

The squirrel earns its likeness to a fox because of its tail, which plumes and curls back against its body in a fluffy firework the color of autumn.

While the fox squirrel is not native to the western United States, it has naturalized here over the last hundred years or so.

The legend goes that veterans from the Civil War and World War I travelled from all parts of the country to a Los Angeles veteran’s hospital. To make them feel more at home, they brought these fluffy red squirrels along with them (often as pets, and even as ingredients for Burgoo Stew—a depression era meal made from whatever ingredients were available).

Finding the southern California habitat, the fox squirrel flourished and spread across the region.

Fox squirrels then, both by human introduction and their own migration over trees and power lines, spread across the western United States.

For over a century, Utah remained outside the fox squirrel’s path. But in 2011 they were sighted in Utah for the first time along the Jordan River Parkway. And in the few years since, they have spread rapidly throughout the Salt Lake Valley and beyond.

©Mark Johnston | NHMU

“They definitely have a foothold,” said Eric Rickart, NHMU Curator of Vertebrate Zoology. “In fact, it's probably at the point now that it would be impossible to stop them. The question is how far they’re going to expand.”

While the fox squirrel naturalized in California and other western states, it did not come without competition. In California, fox squirrels entered territory occupied by other native animals, namely the western grey squirrel (Sciurus griseus).

Smaller in size, though not dwarfed by their foxy counterpart, the grey squirrel has been forced into the foothills and less urban areas of a habitat now shared with fox squirrels.

Rickart doesn’t believe the same sort of competition will occur in Utah, however. The area that fox squirrels have invaded is shared by two Utah-native squirrel species—the rock squirrel, and the American red squirrel. While these three squirrel species now share the same region, they occupy different niches within it.

Where fox squirrels have a relative tolerance to high-traffic, urban areas, both rock squirrels and American red squirrels are more averse to those environments. The rock squirrel also favors burrowing to tree-climbing, unlike fox squirrels. And American reds are specialists in that they mostly eat the seeds of conifer trees, which grow most commonly outside urban areas. Fox squirrels are generalists in their ability to eat a variety of different foods.

“It will be interesting to see how far east and how far upslope the fox squirrels go,” mused Rickart. “And how they spread along the Wasatch Front, and whether or not they can cross large areas that don’t have trees.”

©Mark Johnston | NHMU

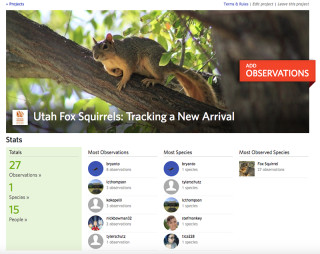

The data we have of fox squirrels in Utah is due in large part, if not exclusively, to the work of Utah’s burgeoning iNaturalist community. By taking photos of fox squirrels wherever they see them, iNaturalist users are documenting their spread along the Wasatch Front. You can learn more about the Utah Fox Squirrels project and see the latest map of all the Utah fox squirrel observations here.

iNaturalist is a free mobile device app that allows people to record their observations of nature and contribute data to scientific research. Users, anyone with internet access and a camera, make photo observations and record them to the iNaturalist web community. There, the community identifies, sorts, verifies, and records observations of wild plants and animals made around the world.

“iNaturalist is a powerful tool for exploring the nature. And it’s very easy to use. It has definitely made me a better observer of the natural world,” says Lisa Thompson, NHMU Exhibit Developer, who stewards citizen science initiatives in iNaturalist on behalf of NHMU. “I look more closely wherever I go. It has made me stop to investigate and record the nature in my neighborhood that I used to just walk by when I walked the dog. Now my dog has to walk a lot more slowly.”

Join the iNaturalist community here, and make observations, wherever you go, whatever you see, to help build our understanding of the world we live in.

*Read Jason G. Goldman's story "Clash of the Tiny—One Pushy Squirrel & the Turf War for L.A.," for more on Fox Squirrels introduction to the West.

Westin Porter is a Digital Science Writer for the Natural History Museum of Utah, a part of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. Our mission is to illuminate the natural world and the place of humans within it. In addition to housing outstanding exhibits for the public, NHMU is a research museum. Learn more.