For a while, crocodile

The ancestors of today’s crocodylians survived two mass extinction events. A new study uncovered a secret to their longevity, which could help conservationists better protect our planet’s most vulnerable species.

Most people think of crocodylians as living fossils— stubbornly unchanged, prehistoric relics that have ruled the world’s swampiest corners for millions of years. But their evolutionary history tells a different story, according to new research led by the University of Central Oklahoma (UCO) and the University of Utah.

Crocodylians are surviving members of a 230-million-year lineage called crocodylomorphs, a group that includes living crocodylians (i.e. crocodiles, alligators and gharials) and their many extinct relatives. Crocodylian ancestors persisted through two mass extinction events, a feat requiring evolutionary agility to adapt to a rapidly changed world. The study’s authors discovered that one secret to crocodylian longevity is their remarkably flexible lifestyles, both in what they eat and the habitat in which they get it.

“Lots of groups closely related to crocodylians were more diverse, more abundant, and exhibited different ecologies, yet they all disappeared except these few generalist crocodylians alive today,” said Keegan Melstrom, lead author and assistant professor at UCO, who began the research as a doctoral student at the U. “Extinction and survivorship are two sides of the same coin. Through all mass extinctions, some groups manage to persist and diversify. What can we learn by studying the deeper evolutionary patterns imparted by these events?”

Earth has experienced five mass extinctions in its history. Experts argue that we’re living through a sixth, driven by habitat destruction, invasive species and changing climates. Identifying traits that boost survivorship during planetary upheaval may help scientists and conservationists better protect vulnerable species today.

Historically, the field has regarded mammals as the poster children for understanding mass extinction survival, lauding their generalist diet and ability to thrive in different ecological niches. Despite their resilience, research has largely ignored the crocodylomorph clade. The paper, published on April 16 in the journal Palaeontology, is the first to reconstruct the dietary ecology of crocodylomorphs to identify characteristics that helped some groups persist and thrive through two mass extinctions—the end-Triassic, about 201.4 million years ago (Ma), and the end-Cretaceous, about 66 Ma.

“There’s a danger of trying to draw conclusions from millions of years ago and directly apply it to conservation. We have to be cautious,” said co-author Randy Irmis, curator of paleontology at Natural History Museum of Utah and professor in the U’s Department of Geology & Geophysics. “If people study mammals and reptiles and find the same patterns with respect to extinction survival, then we might predict that species with a generalist diet may do better. That information helps us make predictions, but it’s unlikely we’ll ever be able to pick out which individual species will survive.”

A hidden past of alternative lifestyles

Living crocodylians are famous for being semi-aquatic generalists that thrive in environments like lakes, rivers or marshes, waiting to ambush unsuspecting prey. Picky eaters, they are not. Young ones will snack on anything from tadpoles, insects or crustaceans before graduating to bigger fare, such as fish, baby deer, or even fellow crocs. Yet the uniform lifestyle of today’s crocodylians masks a massive diversity of dietary ecologies in which past crocodylomorphs thrived.

During the Late Triassic Period (237–201.4 Ma) Pseudosuchia, a broader evolutionary group that includes early crocodylomorphs and many other extinct lineages, ruled the land. The earliest crocodylomorphs were small-to-medium-sized creatures that were rare in their ecosystems, and were carnivores that mostly ate small animals. In contrast, other pseudosuchian groups dominated on land, occupied a wide range of ecological roles and exhibited a dizzying diversity of body shapes and sizes.

Despite their dominance, once the end-Triassic extinction hit, no non-crocodylomorph pseudosuchians survived. Whereas hyper-carnivore crocodylomorphs appeared to also die off, the terrestrial generalists made it through. The authors hypothesize that this ability to eat almost anything allowed them to survive, while so many other groups went extinct.

“After that, it goes bananas,” said Melstrom. “Aquatic hypercarnivores, terrestrial generalists, terrestrial hypercarnivores, terrestrial herbivores—crocodylomorphs evolved a massive number of ecological roles throughout the time of the dinosaurs.”

Something happened during the Late Cretaceous Period that set crocodylomorphs on a decline. The lineages specialized for diverse ecologies began to disappear, even the terrestrial generalists. By the end-Cretaceous mass extinction event (punctuated by the meteor that killed the non-avian dinosaurs), most of the survivors are semiaquatic generalists and a group of aquatic carnivores. Today’s 26 species of living crocodylians are nearly all semiaquatic generalists.

Beyond the smile of a crocodile

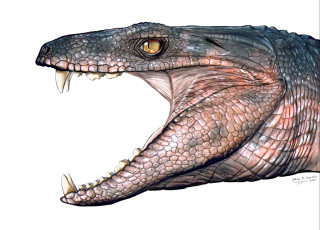

How do scientists parse the food on multi-million-year-old menus? They analyze the shape of fossilized teeth and skulls to glean the basis of an animal’s diet. A jaw stacked with tiny knives was likely slicing and puncturing flesh. A mortar-and-pestle-like grill probably broke down plant tissue. Skull shape dictates how an animal moves its mouth, providing a clue to its eating habits. Deciphering ancient animal diets reveals where it would have hunted, which the authors call dietary ecology.

It was a massive undertaking. The authors visited zoological and paleontological museum collections across seven countries and four continents to get the fossil specimens they needed. They examined the skulls of 99 extinct crocodylomorph species and 20 living crocodylian species, creating a fossil dataset spanning 230 million years of evolutionary history. The researchers had previously built a database of living non-crocodylians to compare with, including 89 mammals and 47 lizard species. The specimens represented a range of dietary ecologies, from strict carnivores to obligate herbivores, and a wide variety of skull shapes.

As semiaquatic ambush predators, today’s crocodylians mostly occupy similar ecological roles in lots of different environments. They do continue to have remarkably flexible diets, perhaps a remnant of their deeply diverse evolutionary past. For critically endangered crocodylians like the Gharial of the Himalaya foothills or the Cuban Crocodile of the country’s Zapata Swamp, dietary flexibility may give them a chance to persist through our current sixth mass extinction. The biggest challenges facing these species are habitat loss and human hunting.

“When we see living crocodiles and alligators, rather than thinking of ferocious beasts or expensive handbags, I hope people appreciate their amazing 200+ million years of evolution, and how they’ve survived so many tumultuous events in Earth history,” said Irmis. “Crocodylians are equipped to survive many future changes—if we’re willing to help preserve their habitats.”

*****

Other co-authors include Kathleen Ritterbush of the University of Utah and Kenneth Angielczyk of the Field Museum of Natural History.

The results published in Palaeontology as “For a while, crocodile: crocodylomorph resilience to mass extinctions.

The research was supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation, the Northwest Federation of Mineralogical Societies, the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, the American Museum of Natural History, the Palaeontological Association, the Paleontological Society, the Geological Society of American and the University of Utah Department of Geology & Geophysics.

Keegan Melstrom

Paleontology PhD. student, Geology and Geophysics at University of Utah and the Natural History Museum of Utah

Download Media

-

Araripesuchus gomesii, Late Cretaceous, terrestrial predator Keegan Melstrom

-

Borealosuchus formidabilis, Late Cretaceous, semiaquatic predator Keegan Melstrom

-

Gondwanasuchus scabrosus, Late Cretaceous, terrestrial predator Keegan Melstrom

-

Skulls of Araripesuchus gomesii (left), a Late Cretacious terrestrial predator and Cricosaurus suevicus (right), a Late Jurassic aquatic predator. University of Central Oklahoma

-

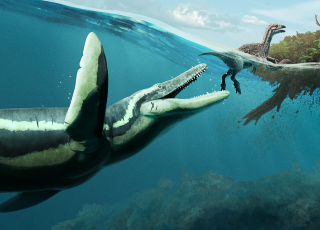

Some 215 million years ago in what is now northwestern Argentina, the terrestrial crocodylomorph Hemiprotosuchus leali prepares to devour the early mammal relative Chaliminia musteloides. Jorge Gonzalez

-

Keegan Melstrom, assistant professor, University of Central Oklahoma with three crocodylomorphs University of Central Oklahoma

-

Keegan Melstrom, assistant professor, University of Central Oklahoma University of Central Oklahoma

-

Study co-author Randy Irmis faces off with a fossil Borealosuchus skull from the Natural History Museum of Utah’s collections. This crocodylian lived approximately 48 million years ago in the American West. Jack Rodgers/Natural History Museum of Utah

Press contacts and links

-

Press Contact

Margaret Chamberlain

Public Relations Specialist

-

Press Contact

Lisa Potter

Research Communications Specialist, University of Utah Communications

-

Press Contact

Keegan Melstrom

Paleontology PhD. student, Geology and Geophysics at University of Utah and the Natural History Museum of Utah

-

Press Contact

Randall Irmis, Ph.D.

Curator of Paleontology