East Africa Finds Reveal New Twist in Human Story

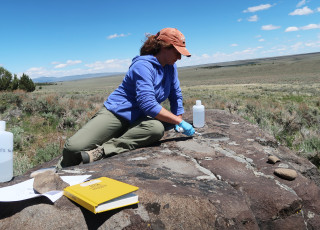

Tyler Faith recording the location of an archaeological site from Gode Ariyo in the Lake Victoria Basin of Kenya, where he has conducted fieldwork since 2009. (Photo courtesy of Nick Blegen)

By Brian Switek

Necessity is said to be the mother of invention. When our species has a need, we create something to solve the problem. This isn’t just a modern habit. New discoveries in the roughly 300,000-year-old sediment of Kenya have allowed Natural History Museum of Utah archaeology curator Tyler Faith and colleagues to track how stark changes in past climates influenced human culture.

The key clues come from Kenya’s Olorgesailie Basin. This is a special place in the story of our species. That’s because this stretch of eastern Africa preserves fossil and archaeological records from much of the past 1.2 million years, Faith says, creating an integrated picture of how life changed through time. “This allows us to look at changes in hominin behaviors, past climates, and past environments prior to and after the emergence of our species, Homo sapiens,” Faith says.

What Faith and an international team of collaborators found, as published in the journal Science, was that significant changes in human culture coincided with dramatic alterations to the local environment. As the climate shifted, so did human culture.

The big picture is of relatively stable environments becoming much more variable. It takes a long-term geological record, like the kind preserved at Olorgesailie, to see. “At about 360,000 years ago,” Faith says, “changes in the shape of the Earth’s orbit about the sun translated to a prolonged phase of exceptionally high climate variability in eastern Africa.” This means the local conditions swung back and forth from very wet to very dry about every 11,500 years or so, as reflected in the geologic and fossil record of the site.

So what did this mean for the people living there at the time? It appears to be a story of major change. Faith and colleagues documented alterations in human culture in the roughly 300,000-year-old sediment of the basin. Older styles of stone tools - known to experts as Acheulean technology - fade away in favor of tools with sharper points or ones that could be modified to make projectile weapons. New materials were part of this transformation. Objects made of obsidian start to show up in this window, the researchers found, and this useful form of volcanic glass must have come from somewhere else as part of a trade network.

Combined with what’s known about the ancient climate and changes among the animals - old forms going extinct and new species replacing them or moving in from elsewhere - this cultural shift seems to be a response to what was happening in the Olorgesailie Basin about 300,000 years ago as the earliest Homo sapiens were just getting their feet under them. The variability in climate and local conditions, Faith says, “would have placed a premium on behavioral adaptations that enhanced our ability to thrive in varied environmental settings.” Over generations, these ancient people were becoming adapted to changing conditions instead of stable ones.

This stands in stark contrast to what was previously expected and involves more than just humans. “When I started working in the region,” Faith says, “the going hypothesis was that there wasn’t any considerable change in eastern Africa’s faunas after 500,000 years ago.” But work by Faith and others has continued to alter this view by finding species no one expected. Excavations at Olorgesailie, Faith says, have uncovered a fossil springbok - a mammal known only from southern Africa today - and a species of giant, extinct zebra that seems to have only lived in the Olorgesailie region. Finds like these help set the background for the conditions under which early Homo sapiens continued to change.

The upshot, Faith says, isn’t that Olorgesailie represents the earliest evidence of certain behaviors or practices. New discoveries could always alter the timeline. Instead, Faith stresses that finds like these only make sense in the context of the broader picture and point to how environmental changes altered our history. “The current evidence indicates that novel behaviors emerged in the context of incredibly dynamic climatic and environmental settings,” Faith says. The times were a-changin’, and our species changed with them.

Brian Switek is the author of My Beloved Brontosaurus, Prehistoric Predators, and a science writer for the Natural History Museum of Utah, a part of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. Our mission is to illuminate the natural world and the place of humans within it. In addition to housing outstanding exhibits for the public, NHMU is a research museum. Learn more.