Archaeologists Extract Plant Matter from Surface-level Metates

By Jude Coleman

The mortar, pestle, and cutting board in your kitchen are modern versions of manos and metates—ancient cooking implements found in archaeological sites around the world. A mano is a hand-held stone tool used with a metate to grind and pulverize food materials from plants and animals. The metate is a large, flat piece of stone or could be ground into a bedrock surface. These bedrock metates, otherwise known as open-air metates, are particularly common at archaeological sites, with the oldest dating as far back as 15,500 years ago. Now, researchers at NHMU are using new techniques to extract microscopic plant residues preserved within the cracks and crevices of bedrock metates to learn more about the people who put them there.

“People have lived here for time immemorial and have been processing native plants on ground stone tools for a long time too,” said Stefania Wilks, an archaeobotanist and research assistant at the Natural History Museum of Utah, referring to the Western U.S. where she conducts her research. That research includes studying plants that people used for food and medicine to learn about traditional lifeways and how the landscapes have changed over time.

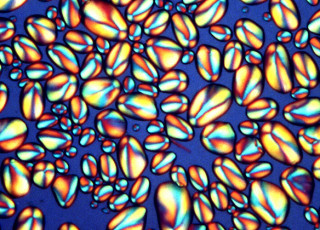

Currently, Wilks is working with NHMU’s Curator of Archaeology Lisbeth Louderback to recover plant residues from metates across western North America. Not just any piece of plant matter, though. Wilks and Louderback work specifically with starch granules, tiny structures within a plant cell used to store energy in the form of carbohydrates. And those granules are itty-bitty: Even the largest granules are smaller than a tenth of a millimeter.

The granules’ small size means scientists can’t see them with their naked eye. They have to extract them from surfaces where people have processed plants, such as ground stone, pottery, and basketry. Louderback suspected that an untapped source of starch granules could be bedrock metates. Although the surface of the rock is exposed to outside elements that would sweep away the granules or degrade them over time, she suspected that small crevices in the rock could be hiding plant residue.

“Through their actions of grinding and mashing, people would have forced these starches down deeper into the stone,” Wilks explained.

Bedrock metates can be obvious or cryptic, and their appearance depends on the type of rock and how it was ground. In Utah, for example, the exposed bedrock is typically sandstone, and the metates are often shaped as an oblong groove. Other bedrock metates are a circular, dish shape, and some are deep and round, like a modern-day mortar. Regardless of their shape, the metates tend to appear in groups, or lined up in a row. “They aren’t sexy like an arrowhead,” Wilks said, “…but they still contain valuable information about what plants people processed in the past”.

Multiple bedrock metates occur along basalt outcrops in the uplands of southern Oregon and are associated with thousands of petroglyph panels. Also occurring among these archaeological features are large populations of culturally significant plants, especially geophytes (those with starchy underground storage organs like roots and tubers). Archaeologists once assumed people only ventured up to the uplands for hunting. “We were up there testing to see if the bedrock metate surfaces were actually being used to process plants,” Wilks said.

To do that, the team compared plant residues on the surface of the metates to those deep within the crevices. Using an electric toothbrush and water, they scrubbed material from the surface of the metate. Then, they added a deflocculant — a substance similar to laundry detergent - to break up clumped particles and release them from deep within the stone. They applied the electric toothbrush again and this time, the material they collected was whatever had been forced down into the stone’s crevices. They repeated this procedure on the surfaces of nearby rocks that weren’t used as metates, to serve as a control.

With samples in hand, the team turned to their microscopes to observe starch granules. Both the metate and control surfaces revealed virtually no granules. But the deeply-embedded samples contained hundreds.

“It increased our confidence that what we were seeing was direct evidence that different plant species with starchy organs were processed on the metate,” Wilks recalled.

Having proven that they could extract starch granules from the bedrock metates, the team then began to establish what plant species the granules came from. It was a time-consuming process: Wilks analyzed hundreds of starch granules from multiple plant species to study their morphological characteristics, then compared them to granules of plant species currently growing in the area. They were able to narrow down the plant family of many granules, and some could even be identified down to the genus level. For example, members of the carrot family were common, including a group of plants called biscuit root. They also found wild grasses — most likely wild rye — and plants belonging to the lily family. These are all plant taxa that were, and continue to be, important food sources for local Indigenous groups.

“Starch analysis is helpful in studying human diets of the past because some plant parts don’t preserve in the archaeological record”, Wilks said. Root vegetables, for example, will break down faster than seeds or grains. This new method of recovering starch granules provides researchers another way to study the role of plants in human diets. It also proves that bedrock metates, often overlooked at archaeological sites, contain valuable information about past human lifeways.