Maddie’s Haddie, Part 2: When You Know, You Know

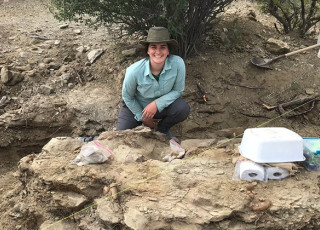

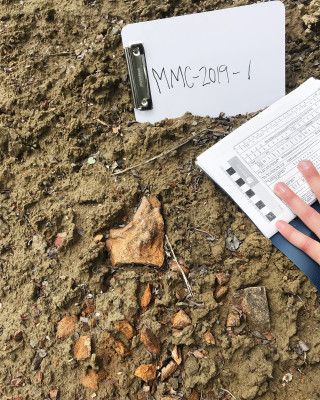

A close-up of a fossil discovered by Maddie Connolly. Skin impressions can be seen to the left. ©NHMU

By Beth Mitchell

Maddie Connolly, first-time paleontology volunteer, put her Day 1 find into Tylor Birthisel’s hands that evening, during what’s known as Campfire Show-and-Tell. This is where Tylor, NHMU Paleo Preparation Lab and Fieldwork Manager, holds court in the circle and volunteers bring him something cool to look at—to see what he knows. Often, he knows a lot.

He’s a paleontologist and geologist by training, and hopes to finish his M.S. degree in the next year or two. But one of his main roles — for which he is revered and beloved — is recruiting (not hard), training (super fun) and managing volunteers in the field, which you could say he enjoys the most.

The volunteers really ‘dig’ Tylor’s skills too. “It’s amazing,” Maddie reports. “He can look at an eye socket fragment, or a piece of one toe, and immediately recognize the ridges and bumps, identify the species, tell you a dinosaur’s life story, hopes and dreams...”

So how does he do that?

When he first started in paleontology about 18 years ago, Tylor is the first to admit he couldn't tell the difference between any of these animals or what bones he was even looking at. “I’ve developed the eye because I've worked in these areas for so long,” he says.

“Based on the knee cap Maddie uncovered,” (which is actually the distal end of the femur, so in essence the knee), he explains, “I can narrow it down pretty quickly just based on the dimensions of the bone and comparing it to the mental inventory in my head.”

With that trained eye, it’s a quick process of elimination. “I knew it was a hadrosaur,” said Tylor, “and that we only have two known hadrosaurs (duck-billed dinosaurs) in Grand Staircase: Gryposaurus and Parasaurolophus.”

At this point, Tylor was unsure if it was Gryposaurus or Parasaurolophus. If he were a betting person, he says he would have put my money on Gryposaurus, because that is the more common of the two.

“In my heart, I was secretly hoping for a Parasaurolophus,” Tylor confesses, “but just because that is the animal I am studying for my Master’s thesis.“

Breaking It Down: How Maddie Found Her Haddie

According to Tylor, a big reason why Maddie stumbled on this fossil is her keen intuition, and some good old-fashioned beginner’s luck.

In Grand Staircase, the rock is generally a salt-and-pepper grey. Fresh dinosaur bones tend to be a chocolate brown color, in part because the sun and environmental conditions haven’t bleached them yet. But when they’ve been sitting out, they’re kind of a tan or buff color.

Sometimes they have an orange hue, which was what Maddie first noticed. But often, a closer look at a rock dashes any hope; it can be petrified wood, or just weathered or oxidized rocks that take on that orangey color. Many paleontologists have been fooled by these tricksters at first glance when hiking the backcountry, and the older more “experienced” folks will walk past them.

Color and shape are good initial clues to give things a second glance. And if all else fails and you don’t know? “There’s always the lick test,” said Tylor, which works because even though the bones are fossilized they still preserve the microscopic pores that suck in a bit of moisture and allows it to stick to your tongue. “It works!”

On the first day of her first time out in the field. Maddie’s instincts were spot on, but she’s the first one to cop to a fair amount of luck, which Tylor confirms.

“I always joke with the newbies that they find the cool stuff because they don’t have as many preconceived notions,” Tylor says.

He confesses that he probably would have stepped over the area Maddie spotted, and headed into the badlands further. “You just assume that the space she was in has been combed over a lot already,” he adds, and then jokes, “And Maddie just wasn’t jaded like I am, right?”

Maddie attributes at least part of her success to her training as a chemical engineer and a researcher. “I’ll admit, I’m really meticulous, so I probably moved painstakingly slowly so I wouldn’t miss anything.”

She was rewarded for this approach with her find, which intrigued Tylor to say the least. He planned to head out to Maddie’s site the next morning, along with Randy Johnson, one of NHMU’s expert veteran volunteers.

The Jurassic Park Moment

When Tylor got to the site, he was shocked and delighted. Maddie had uncovered a fair amount of one of the legs relatively easily.

“It was Jurassic Park-style, where she had basically just brushed some rock and dirt away,” Tylor remarked, adding, “Often it’s more like hammering and drilling through hundreds of pounds of rock.”

Plus, the more the team brushed and uncovered, it became clear just how rare the find was, and assured the team that, as Tylor put it, “This one was definitely coming home with us.”

You see, the NHMU team can afford to be selective. And during these field work days, Tylor and other paleontology experts are typically walking back and forth between volunteers’ finds, doing an on-site evaluation.

“We don’t necessarily collect everything,” explained Tylor. “Sometimes it’s cool that someone found a leg bone, but it’s an isolated bone. And if we can narrow it down considerably to the group of dinosaurs, I can assess whether it’s going to be scientifically enlightening for us.”

It’s important to note that Tylor and the team still document and record the sites they find—even in Grand Staircase, where NHMU has been collecting for 20 years—they just don’t bring everything back to the Museum.

“There are a few factors that justify bringing it back to the Museum,” Tylor shared, “like how complete the skeleton is; what type of animal it is; and the rarity of that animal.”

What was remarkable about Maddie’s find is two-fold. First off, the femur, tibia and fibula were associated to indicate that most of the leg was articulated, meaning that these—and maybe multiple bones—may still be life position.

“Basically it means that the bones aren’t scattered,” Tylor said. “It’s almost like the animal died and got buried pretty quickly, so the bones are still connected in a life-like skeleton.”

This doesn’t happen a lot; bones are often scattered by predators who pick the carcass over, or that the bones on the surface get eroded and pulled apart by the weather.

“The fact that all the bones were articulated and still together was a really good sign,” said Tylor. “We were sure that Maddie’s discovery was worth spending more time on.” And it was.

It didn’t take a long time to see that there was a complete foot on the end of the leg, which led to a pelvis in the other direction. And because the rock wasn’t super hard, the team of Maddie, Tylor, Randy, and a few of the other volunteers worked fast—in paleontology standards anyway.

It wasn’t long before the team knew what they were looking at: a juvenile Gryposaurus.

How Tylor Knew

“I already had it narrowed down to the group [hadrosaurs], and once we started uncovering the pelvis (hips) I was able to get a pretty good idea,” Tylor says.

He explains that the pelvis in Gryposaurus is different from Parasaurolophus, so that was pretty clear from the shapes. As to its age, Tylor saw that the size of the limbs were about two feet long. The limbs of adult Gryposaurus can get up to five feet long. Additionally, he noted that it didn't appear that all of the bones had fused yet—a trait commonly found in adult animals.

So Tylor, Maddie, and a few excited volunteers knew what they had. But they also knew that they had to move it—and carefully.

Read part three in the series here.

Beth Mitchell is Senior Manager of External Relations at the Natural History Museum of Utah, a part of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. Our mission is to illuminate the natural world and the place of humans within it. In addition to housing outstanding exhibits for the public, NHMU is a research museum. Learn more.