Maddie’s Haddie Part 3: What did we find and why does it matter?

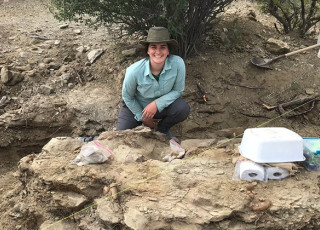

After digging up the specimen, parts are placed in field jackets for transport to the Museum. ©NHMU

By Beth Mitchell

To bring everyone up to speed, this is the grand finale of the epic paleontology field work adventure of volunteer Maddie Connolly and the rest of the Natural History Museum of Utah team. We recommend you start at the beginning.

In part one, we meet Maddie and go behind-the-scenes of NHMU paleontology field work in Grand Staircase Escalante, including what Maddie found on her very first day ever out in the field.

In part two, we learned how to spot bones in the field, as well as how the experts use their skills and experience to identify the genus and species of a dinosaur—often with only fragments of bone in a ziploc bag.

Maddie had found a juvenile Gryposaurus, a genus within the group Hadrosauridae, commonly known as duck-billed dinosaurs.

Over the course of about two weeks, with a few team members coming and going along the way, the field team had two tasks: to excavate the block containing the skeleton, and to transport it more than 250 miles north to the Natural History Museum of Utah in Salt Lake City.

Seems easy enough, right?

Dr. Randy Irmis, chief curator and curator of paleontology at NHMU, wasn’t on-site the week Maddie’s Haddie was found, but he came out the week after, when the excavation began in earnest.

“The good news is that it was mostly right near the surface, so we didn’t have to remove much rock above it, and therefore the initial excavation went pretty quickly,” Irmis said.

Quickly in paleontology is a relative term; it took about two weeks. But it’s what they found during excavation of the Gryposaurus that was really exciting: a whole lot of skin impressions.

The Significance of Skin

Although it takes specific environmental conditions and geological processes to set and preserve skin impressions on fossils, the impressions themselves are not extremely rare. But in the case of Maddie’s Haddie, a couple of things made these ones special.

“Although we have a fair amount of duck-billed dinosaur specimens from Grand Staircase that have some skin impressions, only a very small number of those have skin impressions over the skeleton which is still in life position,” explains Irmis. “And even fewer of those are juvenile.”

So why was the team excited about these juvenile skin impressions?

“One of things we’re always seeking to better understand,” says Irmis, “is how these animals may have changed as they grew up.”

Of course paleontologists can determine some answers to that question by looking at the bones – because there is a significant fossil record – but that’s just one side of the story.

“Now that we have all of these skin impressions from Grand Staircase specifically, we can also ask similar questions using the skin,” Irmis says. “For example, does the shape, size, or arrangement of the scales change as the animal becomes an adult?”

NHMU Paleontology Collection Manager Carrie Leavitt-Bussian knows first hand how interested researchers are in fossilised dinosaur skin.

“When people consider skin impressions,” Carrie reports, “they look at the shape of the dermal denticles (or scales), including how big they are, if there is any pigmentation on it. The interest here is because a juvenile skin impression reveals more about the ontogenetic growth – or the lifetime growth – of the species.”

But why does an animal’s growth chart matter so much? And to whom?

Turns out, it matters a lot to paleontologists, and to the field of paleontology.

Take a moment and consider the difference between an infant and a grandparent, especially the skin, the teeth, the bones. If you’d never seen the life cycle of a human being, one could come to the conclusion that a baby and an older person were completely different species.

The same is true for paleontologists who discover, study, and identify dinosaurs without ever seeing them in real life. In some ways, and especially in decades past, the identification of fossils is a process of discerning differences based on a known unknown, i.e., the full record of a species from birth to death.

Carrie makes this crystal clear: “When we know more about the size and appearance of dinosaurs at what age, it can help a lot with identification and classification. When you have a wider age range of a species, it’s easier to determine whether a specimen is really a new species – which is rare – or that it’s a juvenile form of a species we know about.”

The bottom line is that the significance of Maddie’s specimen was its age and the skin. Randy Irmis shares that whenever NHMU makes a decision to add a specimen to its paleontology collection, it is because of its potential contribution to paleontological research.

“The reason why we collect fossils is for research purposes.” he says. “We wouldn’t collect something if we didn't think it was important for the research that we're doing, as well as for research by future scientists.”

Maddie’s Haddie was destined for NHMU, so it was full-speed ahead on excavation and preparation for an air lift.

The Struggle is Real

The team worked with some urgency, as the logistics can get complicated quite quickly.

“We spent a lot of time working on the skeleton,” Randy Irmis remembers, “and ended up taking it out as two separate large blocks: one containing parts of the neck, shoulder and arm, and another containing the rest of the skeleton behind the shoulders.”

The team then created two plaster field jackets to protect the block, and prepared to move them into a net that would soon be hooked to a helicopter for transport to a truck for the long drive back to Salt Lake.

According to Randy Johnson, a nearly twelve-year paleontology volunteer with NHMU and a veteran member of the field work operation in Grand Staircase, the initial excavation may have been straightforward, but it wasn’t exactly easy.

He estimates that between the initial uncovering of the block, jacketing it, and moving it around, he and the others logged about 200 hours.

“It got to be a really thick block, and weighed over 2000 lbs,” Johnson describes. “It took a group of five of us adults to flip it into the net.”

The team from NHMU was motivated to get it ready because at the end of the season that year, NHMU had a helicopter available in collaboration with the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and some other partners.

“Based on prior experience, we thought for sure that once we got the blocks ready and done up, they would be lifted out by helicopter without a problem,” Randy Irmis explains. “After all, it would be a real pain to drag them.”

But after the team connected the net with the larger of the two blocks to the helicopter, and the helicopter pilot attempted to lift it, the group realized pretty quickly that it was just too heavy.

“The helicopter just sort of buzzed in the air, with the net still on the ground,” Randy Johnson reflects. “It wasn’t going anywhere.

At that point, the team knew that they were playing the long game. “We knew we wouldn’t get it out that season because we needed additional funding for a larger helicopter,” says Randy Irmis.

And just a few months later, COVID shut everything down.So part of Maddie’s Haddie sat in the wilderness off the grid, undisturbed. “With something that far into the backcountry, and with only interior roads, you’d pretty much have to know exactly where to look to find it.”

“Sometimes we place a tarp over the jacket,” Randy Johnson adds. “And then put some sediment over the top of that, just to be safe.”

Thankfully, in May of 2021 the BLM was able to get some funding for helicopter work. And with a larger helicopter and skilled piloting, the blocks were delivered safely to a truck and trailer parked at the turn off to Kodachrome Basin State Park, bound for the Museum.

The Fate of Maddie’s Haddie

So where is Maddie’s Haddie now? It’s in line for the paleo prep lab at NHMU — right where it needs to be..

“It’s a lot easier to collect things than to prep them,” confirms Paleontology Preparation Lab Manager Tylor Birthisel.

In truth, there are several factors that determine how quickly a fossil will be prepped. Scientifically-speaking, it’s about research priority. If the fossil has a direct impact on ongoing research or new research being worked on, we’ll do our best to get it prepped as quickly as possible.

But that’s only one factor, and sometimes it’s more practical than that. “Sometimes — oftentimes, even — it’s a matter of space,” reveals Tylor. “We only have a couple of places in the lab where we can accommodate such large blocks like Maddie’s. So we have to wait for one to open up.”

It’s also about matching the right specimen with the right preparator — nearly all of whom are volunteers. Tylor endeavors to match a volunteer’s experience and skill level to the specific prep work that each specimen requires.

With Maddie’s Haddie, the block contains fossilized bone as well as those skin impressions. “Normally, you’re just removing rock around the bone,” Randy Irmis explains. “But in this case the rock contains a skin impression, so you have to work slowly and meticulously to preserve that.”

Something for Everyone

Even so, the prize — so to speak — is always worth the rocky ride. And everyone has their favorite part of the fossil discovery process.

For Tylor Birthisel, it’s sharing a love of paleontology. “When someone finds something that's worthy of collecting — really cool or beneficial to the Museum — I'm so excited for them; to be able to give them an experience like the kind I had when I first started in paleontology.”

For Carrie, it fulfills a childhood dream: “I love going out in the field and digging. But I also love the end result. I always wanted to be a librarian, but for fossils.”

For Randy Irmis, who is also the chief curator at NHMU, the field work is in service to a much larger story. It’s the scientific method in action. “The research questions are what drives us to go collect the specimens, which are the data that help to test hypotheses. In paleontology, those data are fundamentally the fossil specimens. So some of those data could already be in the collections, but oftentimes you need to go out and gather more data, which requires collecting more specimens — for study by all researchers, both current and future generations.”

For Randy Johnson, field work offers a unique perspective — both literally and metaphorically. “When you’re out there, all by yourself, immersed in your surroundings, you really get the big picture of things. Dinosaurs give us over 170 million years of history, but that’s in 3 billion years of the earth’s existence. And humans (at least the homo genus) have only been around for 2 million years. This work tells the story of life on earth, and there’s so much more we don’t know.”

And we have to give Maddie the last word on her Haddie: “It’s the most exciting thing that’s ever happened to me. I joke that I’m going to tell my future children that I love them less than I love my dinosaur. But really, it’s the community of people seeking a shared experience through a love of hiking, and backpacking, and discovery.”

To become a volunteer at NHMU, keep an eye here.

Beth Mitchell is senior manager of external relations at the Natural History Museum of Utah, a part of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. Our mission is to illuminate the natural world and the place of humans within it. In addition to housing outstanding exhibits for the public, NHMU is a research museum. Learn more.