NHMU's Barrier Canyon Mural

By Michael Mozdy

Located behind the Admissions Desk on the first floor of the Natural History Museum of Utah is a 60-foot by 12-foot mural that faithfully replicates some of the most significant rock art in the American Southwest. It is perhaps the largest single painted art canvas in a U.S. museum collection. It’s called the Barrier Canyon Mural, and it replicates not just the figures found on the rocks, but the cracks, chips, and subtle coloration differences of the rock itself as it exists in Horseshoe Canyon.

Horseshoe Canyon, once called Barrier Canyon, is located in Canyonlands National Park in Southeastern Utah. This somewhat remote canyon contains an important pictographic panel (and the largest in Utah), called the Great Gallery. This panel is 200 feet long, 15 feet high, and contains 20 anthropomorphic figures, the largest of which is over seven feet high. In other words, it’s massive.

(As an interesting side note, this was also the location to which adventurer Aron Ralston hiked after cutting off his arm, which was trapped by a boulder, dramatized in the movie “127 Hours.”)

The figures in the Great Gallery have a heroic size, intricate torso decoration and no extremities. Some have large “bug eyes,” square heads, or crowns, and one has a birdlike beak. Many think they look like mummies or specters, and given their size, they are certainly a bit intimidating.

The pictograph panel is significant – it is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. In fact, it is so influential that archaeologists named this distinctive style the Barrier Canyon Style, and similar rock art has been found throughout the Four Corners region. The style features huge panels, virtuoso painting techniques, both life-size and monumental anthropomorphic figures, a large variety of figure types, and the inclusion of animal, bird, snake, and plant images with spirit figures.

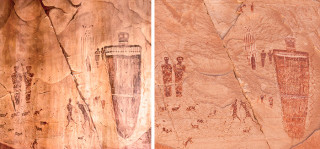

A side-by-side comparison of a section of the Great Barrier Mural and the actual rock art from the Great Gallery. Can you tell which is which? © NHMU and photo by Greg Willis / Flickr.

A Public Works Painting from 1940

While the huge painting in NHMU seems like a recent reproduction, the Barrier Canyon Mural was in fact created more than 75 years ago. Artist Lynn Fausett was employed by the federal Works Progress Administration (WPA) to paint the mural in 1940. The WPA employed artists to create murals in public buildings during the Great Depression.

Originally exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in New York City, the mural was moved to the Denver Art Museum during World War II for safe keeping. It stayed there in storage until 1964 when it was incorporated into a traveling exhibit organized by the Amon Carter Museum of Western Art in Texas. Fausett repaired it before it went on exhibit. It was shown in nine venues across the American West in the 1960s (including Salt Lake City). During this time, the mural was unrolled, hung for exhibition, and re-rolled at least a dozen times.

The Utah Museum of Natural History acquired the mural in 1969 and it was displayed in the old museum location (George Thomas Building) on the University of Utah campus. In 2011, we needed to move the mural to our new location after 40 years of dust and weathering while on exhibition. The story of what it took to move it is a fascinating one – read Irons, Paint, & Pulleys.

Fausett was a good choice to be the mural artist. He was born in Price, Utah, in 1894 and trained at BYU, the University of Utah, and the Art Students’ League of New York, where he also served as president. He painted American landscapes, history, and everyday life. He was one of the foremost muralists of the Mormon pioneer experience. Given his ties to Utah, it is only fitting that he painted the Barrier Canyon Mural.

Elzy J. Bird, Director of the Utah Federal Art Project, was asked by the Indian Arts and Crafts Board (Dept of the Interior) to reproduce the Great Gallery as a mural. Bird chose Fausett to be the lead artist on the team, but there were five other artists, too: Frank Mace, Henry Rassmusen, A. Ray Toleman, Frank Maurer, and Eldon Allen, as well as a photographer, Bob Jones.

In a crazy turn of events, Fausett actually missed out on the week-long trip down to Horseshoe Canyon he had planned where the team created the master sketches and took many photographs. He was set to go but at the last minute he was rushed to the hospital for emergency hernia surgery.

How exactly does a team faithfully reproduce such a huge work of rock art? Bird writes about this process in his memoirs:

First, at the base of the paintings, with white chalk we placed scratch marks on the cliff, one foot apart horizontally. There on the long bamboo poles, mentioned before, we placed black marking tape spaced at one foot intervals along the length of the poles. By holding the poles upright against the cliff. [sic] This gave us a quick guide, both vertically and horizontally, in increments of one foot. We next made up an illustration board with grid-lines in pencil one inch apart both ways – this was for our master sketch.

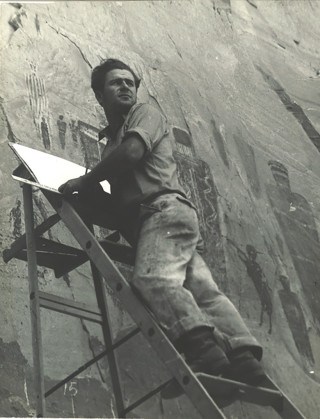

Artist A. Ray Tolman painting a detail study of the Great Gallery in 1940. Note chalk lines at bottom to help them create the master sketch.

Back in Salt Lake City (a top-floor studio at 222 South West Temple St., to be precise), Fausett stretched the huge, heavy duck canvas over a wooden frame and painted the surface with white tempura. He then marked the canvas in one-foot grid lines and completed a rough charcoal drawing to scale, based on the master sketch. At that point, the whole team of artists proceeded with the actual painting of the details. They finished it in record time, between September and December of 1940, in time for the January 1941 exhibition at MOMA.

Fausett and team actually broke the Great Gallery rock art into two murals: the 60-foot one that hangs at NHMU and a 20-foot mural of the section called the "Holy Ghost,” which can be found at the USU Eastern Prehistoric Museum in Price. The display in Price brings Fausett’s art closer to Horseshoe Canyon itself and preserves the artist’s work in a museum in his hometown.

In a letter to Dean Brimhall in 1964, Bird adds a few last thoughts about the mural: “It is not a great work of art – it never was intended as such. It was made as well as we could make it in the time we had to do it. Both Lynn Fausett and your friend Mrs. Sprang could do a better one given the time and money with which to do it. Also, who would sponsor it? Where would you put it? There are many questions to be answered, such as who would actually appreciate it, except a few nuts like us?”

Well, we found a pretty great place to put it, we certainly appreciate it, and we think that it’s pretty darn good and a great piece of history, too.

For more information about Horseshoe Canyon’s Great Gallery, when it was painted, and what it could mean, read Bold Figures, Blurred History.

Michael Mozdy is a Digital Science Writer for The Natural History Museum of Utah, a part of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. Our mission is to illuminate the natural world and the place of humans within it. In addition to housing outstanding exhibits for the public, NHMU is a research museum. Learn more.