Bold Figures, Blurred History: The Great Gallery in Horseshoe Canyon

By Michael Mozdy

NHMU displays a 60-foot long mural on the 1st floor, a faithful reproduction of the Great Gallery painted in 1940 by WPA artist Lynn Fausett (read NHMU’s Barrier Canyon Mural for more information). This iconic pictograph panel is beloved by southern Utah adventurers and its study prompted archaeologists to recognize a new rock art style they named the Barrier Canyon Style. The style features huge panels, virtuoso painting techniques, both life-size and monumental anthropomorphic figures, a large variety of figure types - mostly with no or very few limbs in an exaggerated elongated style - and the inclusion of animal, bird, snake, and plant images with spirit figures.

Archaeologists have long wondered what time period the Great Gallery was painted, but dating rock art is notoriously difficult. Petroglyphs are created by chipping, scraping, or pecking rock, and a patina is formed when rock is chipped away. These rock art patinas are brown or black stains of hydrous iron and manganese oxides. The darker the patina, the older the petroglyph. This helps to determine which petroglyphs are older than others, but not to know the date of their creation.

Even with pictographs, where some sort of substance was painted onto the rock, there is often not enough material to collect in order to perform radiocarbon dating (especially without harming the pictograph). What’s more, natural weathering and adhering to other material in the rock make getting a clean sample of paint material virtually impossible.

Art Historians Weigh In

Given the challenges to radiocarbon dating the organic material in rock art, archaeologists and rock art specialists throughout the later 20th century estimated the age of Barrier Canyon rock art by indirect methods. They estimated dates by comparing to previously dated sites in the vicinity and looking at the stylistic content of the art. For instance, if the bow and arrow is present in rock art, then it must have come after the introduction of these weapons. Likewise, if horses appear in the rock art, it must have been made after horses came to North America with the Spanish in the 1500s.

Archaeologists haven’t agreed on a specific time period, but most attribute Barrier Canyon Style pictographs to a people known as the Desert Archaic culture who lived in Utah over a long time span, from 8000 B.C. through 500 A.D.

Some believe that the Great Gallery was created by Early Archaic people as early as 5,000 B.C. because the anthropomorphic figures resemble clay figurines found at nearby Walters Cave from that era (the figurines were found with sandals that were radiocarbon dated to the Early Archaic period). More commonly, archaeologists have hypothesized that the time period was the late Archaic, between 2,000 B.C. and 0 A.D., before the spread of agriculture, the introduction of the bow and arrow, and the establishment of the Fremont culture in the area.

Polly Schaafsma, a rock art authority in the southwest, believes that Barrier Canyon style dates to the late Archaic period, between 500 B.C. and 500 A.D. She cites the similarities to other rock art and archaeological materials in the Colorado Plateau, and “the occasional overlap in anthropomorphic types between the Barrier Canyon Style and those painted by the San Juan Basketmakers” who lived south of Horseshoe Canyon.

Schaafsma’s time frame includes the rise of a new cultural group in Utah called the Fremont, but she does not believe that they painted the Great Gallery (the Fremont cultural complex is dated from around 250 A.D. to 1300 A.D.). In addition to noting many stylistic differences between the more geometric Fremont rock art and the Barrier Canyon Style, she elaborates, “It is of considerable interest that the bow and arrow, which is commonly represented in Fremont art, is absent in all recorded examples of the Barrier Canyon Style.” This claim is not as cut and dried as it once was, since the bow and arrow have subsequently been identified in other Barrier Canyon Style art, and the bow and arrow have been found to have entered the Glen Canyon region by 100 A.D. Schaafsma provides other evidence, however, noting that when one figure has been painted over another (called superimposition), it is always a Fremont style that is over a Barrier Canyon Style. She concludes, “Thus, this line of evidence suggests that the Barrier Canyon Style preceded the Fremont in date.”1

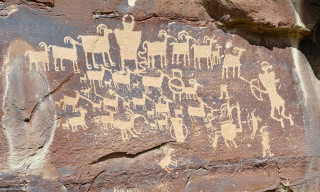

A good example of Fremont petroglyphs: the Great Hunt panel in Nine Mile Canyon, eastern Utah. Note the figures with bows and arrows on the right. Photo: Bureau of Land Management / Flickr.

An Enlightened Geologist

Joel Pederson doesn’t normally study rock art, but when a friend talked to him about the Great Gallery, he realized that he could apply his geologic lab techniques to dating the artwork. A 2014 study done by Pederson and Steven Simms at Utah State University dates the "Holy Ghost" section of the Great Gallery consistently with Schaafsma, if not younger. They combined geologic data and a technique called optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) to reach their conclusions.

First, they noted that the canyon was filled with flood-driven sediment above the height of the Great Gallery until about 7,000 B.C. By studying when this sediment was removed enough to expose the area where the Great Gallery exists, they arrived at around 4,000 B.C. as the earliest date when it could have been painted.

Then Pederson had the bright idea of dating a large piece of the rock art panel that had cleaved off of the "Holy Ghost" section of the rock wall and fallen face-down on the ground. OSL is a fairly new technique being used by geologists to date inorganic material, just like radiocarbon dating is used to date organic material.

Excited Electrons

It turns out that the crystalline structure of quartz, commonly found in sandstone, has natural imperfections that allow for something mysterious to happen at the atomic level. In the normal life of a quartz crystal, naturally occurring radiation excites its electrons, which causes them to “jump” from their normal orbits around the atomic nucleus into what is called the conduction band, which is the outermost electron level of an atom – the one that can interact with other atoms. These excited electrons naturally diffuse back to the valence bands from which they came. However, crystalline imperfections in quartz can cause electrons to become trapped between the conduction band and the valence band. What’s more, they get trapped at a characteristic rate depending on how imperfect the crystals are and they accumulate over time.

When exposed to light or heat, these electrons jump back to the valence band and release a photon of light (called luminescence). Scientists can use sensitive equipment to measure the light emitted by quartz sediment to determine the last time it was exposed to light.

This is precisely what Pederson’s team did with the fallen rock face sample. His students and colleagues not only measured the fallen rock face, but quartz sediment the boulder landed on; they even radiocarbon dated a leaf that was serendipitously trapped between the two when it fell. All three came back with the same date: 900 years ago, at 1100 A.D.

What Pederson measured is called “bleached” quartz that had been exposed to sunlight for a while in the canyon, then “re-charged” while it lay face-down on the ground. By analyzing the depth of this bleaching into the rock face compared to what signal should have existed if it had not fallen, they determined that the rock face had been exposed to sunlight for at least 700 years before it fell to the ground. There is some error in this calculation, up to some centuries, so their new time window for the painting of the "Holy Ghost" section of the Great Gallery (conservatively estimated) is between 0 A.D. and 1,100 A.D.

Joel Pederson examines the “Holy Ghost” section of the Great Gallery. Photo: Joel Pederson / Utah State University.

A Sketch of the Painters

This younger dating of the Great Gallery has great implications about who may have painted it and what the figurines mean. The first millennium A.D. was a time of transition in southern Utah - the hunting and gathering Late Archaic culture was disappearing and the more agrarian Fremont culture and Basketmaker culture just to the south were blossoming. The art history evidence leans towards the Archaic peoples painting them, but if the science of Pederson’s study is correct, then it would have been during a time when multiple cultures were encountering each other and the world of hunting and gathering was merging with that of agriculture.

Very little archaeological evidence has been found in Horseshoe Canyon itself. One excavated site from the Claflin-Emerson expedition in 1930 revealed three occupational levels: a pre-ceramic level (this could have been the Early or Middle Desert Archaic culture), and a Fremont and an Ancestral Puebloan (Anasazi) level which appear to have been mixed.

But perhaps these cultures weren’t so separate. The 8,000-year history of the Archaic peoples covers a lot of time and a lot of change. These people developed new technologies to get their food from many different sources as climate patterns changed. We know that the Colorado Plateau (and the American Southwest in general) was not an isolated place. In northern Utah, the Promontory peoples came through around 1300 A.D. from subarctic Canada; many trade routes with Mesoamerica existed throughout the millennium prior to that, bringing cultural rituals, corn, and chocolate to our area; and evidence has been found along the coastline of California that Paleocoastal peoples were living and trading up and down the west coast as far back as 9000 B.C.

“There’s a group of us who think that some of the Fremont groups are a northern variation of the southwestern Puebloan people,” argues Glenna Nielsen-Grimm, the NHMU Anthropology Collections Manager. “There is a distinction, but they are living in a similar way. The Vernal Fremont, for example, seem to be a great example of Basketmaker homesteaders who moved north, up the Green River.”

Perhaps the Archaic people and their neighboring Basketmaker or Fremont peoples freely exchanged knowledge of foraging, farming, and other cultural practices. Perhaps the Archaic people were so close technologically to the Basketmakers that when they intermarried and grew together over a few generations, they became what we now think of as the Fremont cultural complex.

"This is more than 'perhaps,'" corrects Steven Simms, co-author of Pederson's OSL paper and professor of Anthropology at Utah State University, "There is considerable archaeological evidence. During the period of the dating of the rockfall, indigenous Archaic foragers encountered immigrant Basketmaker II farmers bringing maize agriculture north of the Colorado River, eventually forming the Fremont."

If these groups were more similar and part of one another than they were distinct, then the dating of the work to the first millennium A.D. means that it happened when there was cultural overlap and cultural exchange. Indeed, the anthropomorphic figurine with little or no appendages has been found throughout the Southwest, indicating that a widespread culture of peoples shared a sense of form and art. Simms sees rock art as "a landscape phenomenon reflecting persistence, reformulation, and integration of art, iconography, and ideology among peoples." In other words, multiple groups of people likely contributed to the Barrier Canyon rock art over multiple generations - encountering the work of earlier artists, adopting and reformulating the iconography, and reflecting the experience of living in that area during their own time. Simms notes that elements of ancient rock art persist in tribes living in the Southwest today, so attributing the Great Gallery to a specific group of people is not only unlikely but misses the point that these important pictographs and petroglyphs represent a thread of cultural sharing over hundreds, if not thousands of years.

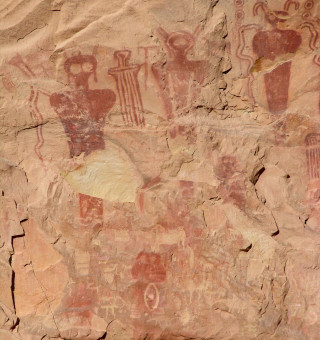

Below is an example of another Utah pictograph located in Sego Canyon (Thompson, UT) that illustrates this cultural continuation of rock art. The dark red painted pictographs are Barrier Canyon Style anthropomorphs (with large "bug-eyes," similar to those seen in the Holy Ghost panel from Barrier Canyon), but lower on the panel you can see pecked petroglyphs on top of this art, likely from the Fremont era.

Pictograph panel from Sego Canyon. Photo: Don Graham / Flickr. Click photo to enlarge.

If your interest in the Fremont is piqued, below is a 24-minute video produced by Utah State Parks, featuring our very own Chief Curator, Duncan Metcalfe, Ph.D.

Finding Meaning in the Figures

One thing is for certain: the anthropomorphic figurines are an amazing look at human art from past millennia. These could very well be the work of shamans, working on the periphery of society, devoted to spiritualism, visions, healing, and prayer. Schaafsma writes: “One senses that the remote, awe-inspiring anthropomorphic forms of the Barrier Canyon Style are beings imbued with supernatural power. It is not unreasonable, considering the content of the paintings, to suggest that we are dealing with a shamanic art.” These could be forms expressing what shamans saw under the influence of hallucinogenic substances in their search to bridge the spirit world and physical world. They could be protection or guardian symbols for an area considered to be sacred.

One of our modern novelists, Ed Abbey, stimulates our imagination about what these figures might mean in his book Desert Solitaire: “These are sinister and supernatural figures, gods from the underworld perhaps who hover in space, or dance, or stand solidly planted on two feet carrying weapons - a club or sword. Most are faceless but some stare back at you with large, hollow disquieting eyes. Demonic shapes, they might have meant protection and benevolence to their creators and a threat to strangers: beware, traveler, you are approaching the land of the horned gods...."

The haunting nature of the Great Gallery anthropomorphs. Photo: iStockphoto.

At its heart, the mystery of the Great Gallery panel is a great example of the wonders of archaeology in Utah. We have yet to truly piece together the evolving cultural complexes that inhabited the Colorado Plateau, from Paleo-archaic peoples through the modern era. We find tantalizing evidence of the material culture they left behind and the art with which they graced the land. We use our best science and our best thinking to date sites and to connect the dots, but we are still left with many hypotheses and much more exciting work ahead.

1Schaafsma, Polly. “The Rock Art of Utah.” Papers of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, vol 65. pp. 129-130.

Michael Mozdy is a Digital Science Writer for The Natural History Museum of Utah, a part of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. Our mission is to illuminate the natural world and the place of humans within it. In addition to housing outstanding exhibits for the public, NHMU is a research museum. Learn more.