The Promontory Culture: Subarctic Canadian People Living in Utah Caves

By Michael Mozdy

It’s 1930, and the world as we knew it had just fallen flat with the great stock market crash. A young man, fresh out of UC Berkeley with his Ph.D. in Anthropology, took a position at the University of Utah to study Pueblo culture. He was Julian Steward, and he would later become a renowned anthropologist with the Smithsonian Institute and Columbia University. His pit stop in Utah during the Great Depression uncovered an unexpected wealth of Native American cultural artifacts.

Steward began exploring the Promontory Point caves on the north shore of the Great Salt Lake. He found some promising signs of Native American occupation. Because he was concerned about heavy looting that was evident in the caves, he quickly began a thorough excavation. Steward meticulously catalogued the site and its artifacts, and the University of Utah received about 250 moccasins and moccasin parts, other hide objects, bison bone, pottery, fiber, arrow shafts, points, and stone tools.

But the Great Depression raged, then so did World War II, and for 80 years the moccasins silently sat, eventually stored at the Natural History Museum of Utah in open wood trays.

Much-Needed Conservation

“With the mashed moccasins and bundles of bison fur, you could not make much sense of what this collection contained,” explains Kathy Kankainen, former NHMU Anthropology Collections Manager.

So, Kathy applied for a Save America’s Treasures grant from the National Trust for Historic Preservation, and received it in 2001. We hired Nancy Odegaard, an internationally known conservator to help make sense of the moccasin collection and preserve them for future study.

Read about the meticulous conservation work to preserve the moccasins in Alcohol, Leather & Time.

Through carbon dating, we’ve learned that the moccasins date to as early as 1150 A.D., with the majority of them dating to the second half of the 1200s.

A Brief History of Drought

The time period for the moccasins is significant. Right around the year 1300 A.D., North American cultures were in the throes of change. Many archaeologists believe that much of this change was due to climactic conditions, specifically drought. One example: the collapse of the Ancestral Puebloan people (also known as Anasazi). The Southwest experienced decades of drought from 1276-1299 (first called the “Great Drouth” by astronomer A.E. Douglass) and this coincides with the time that the Puebloan people abandon their cliff dwellings in the Four Corners Region. Without rain, crops cannot grow, and large, sedentary agricultural cultures would experience famine and drastic loss of life. Climate data suggest that the drought was even more severe in Nebraska, lasting upwards of 38 years, until 1318.

Another example is the 20 years of drought in the Mississippi plains area that hit in the late 1300s and the startling decline of Cahokia, the largest prehistoric site in the eastern U.S.1

One final fact about the milestone year 1300 A.D.: that’s the last time we find evidence of the material culture of the Fremont people in Utah, a culture that by that time had given up on growing crops and instead relied on foraging and small game hunting.

The Promontory Peoples Thrive While Others Disappear

Dr. Jack Ives, an archaeologist with the University of Alberta, Canada, and friend of NHMU has taken up Steward’s work in the Promontory caves 80 years later. His excavations from 2011-2014 have yielded a ton of more artifacts and data about the people who lived there. He found evidence of feasting, gaming, sophisticated hide tanning, and plenty of children. In short, these people were doing very well.

Read more about Dr. Jack Ives’s discoveries in This Was the Place: Athabaskans Gambling on a New Life in the South.

So, in the late 1200s, just decades before the Fremont disappear, and amid a time of drought and crisis for agricultural peoples, the big-game hunting people who inhabited the Promontory caves in Utah were thriving. What’s more, there was a Fremont settlement just over a mile away! There must have been a startling contrast in the quality of life between these two peoples who were undoubtedly in contact with each other.

But who were these people?

Moccasins Tell the Tale

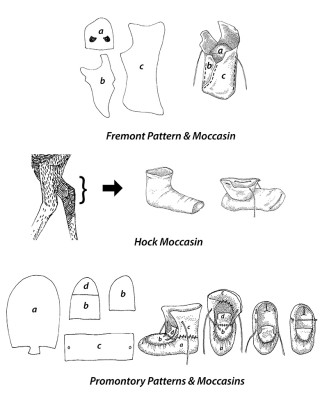

The Promontory moccasins are pivotal evidence for Ives and his colleagues. Like Steward 80 years earlier, Ives believes that the unique style of moccasin comes from a subarctic Canadian group of people generally known as Dene (which describes the language they speak). The figure below shows the unique construction of three styles of moccasins found in Utah.

Reproduced courtesy of the University of Utah Press.

The Promontory moccasins exhibit three other traits specific to the moccasins made by subarctic Canadian peoples: 1. The stitching was fine, with 7-8 stitches per centimeter, while the stitching for Fremont and hock moccasins was coarse, with one stitch or less per centimeter, 2. The hides used were fully and evenly tanned while other Great Basin moccasin hide was thick and not all of the hair was removed, and 3. There were porcupine quills and decorative quillwork on the moccasins, which is completely absent in other Great Basin moccasins.

The moccasin on the left is from Promontory Cave and exhibits the construction pattern, fine stitch work, expertly tanned leather, and decorative quillwork that are unique to the Promontory moccasins and different than others in the Great Basin region. On the right is a pair of replica moccasins (complete with missing upper portions) based closely on the original design. Replicas made by Nancy Fonicello, on display at NHMU. © NHMU.

A moccasin similar to the Promontory ones was found in the Yukon ice patches in Canada, and dates to 700 years earlier, and a very similar one was found in a cave in Colorado from roughly the same time period. This evidence, together with the fact that Dene peoples in the 18th and 19th centuries continued to wear similar moccasins, points to the Promontory peoples as coming from subarctic Canada.

Why so much reliance on moccasins for evidence? Ives and his co-authors write: “Moccasins frequently signal cultural identity, provide an avenue through which (primarily) women can show the skill through which they care for family members, and are often conservatively retained long after other elements of western dress become common.”2 In other words, moccasins are so important to Native American cultural identity that we see the same construction and adornment over 1,000 years of history.

The Promontory Phase: a Culture in Transition

One way to trace the connectedness of Native American cultures is through the languages they speak. Linguists have created detailed language family trees throughout the Americas, and some surprises have emerged.

"Some languages that are geographically close to one another may actually be 'genetically' unrelated, in that they belong to different language families," asserts Marianna Di Paolo, Director of the WRMC Shoshoni Language Project, Associate Professor of Anthropology and Adjunct Associate Professor of Linguistics at the University of Utah.

Native American tribes in Utah today – Ute, Goshute, Paiute, and Shoshone – all speak languages of the Numic branch of the Uto-Aztecan family of languages. However, the one other Native American tribe found in southern Utah, the Navajo, speak the Diné (or Dene) language. The Navajo and the Apache, both found in the Southwest, speak a language closely related to their far northern linguistic cousins of the Pacific NW from northern California to Alaska and the interior of Alaska and Canada.

According to the linguistic theory of how Native Americans are related, some of the Dene peoples must have migrated southward and eventually become the Navajo and Apache peoples. There is much discussion about what path and what time period this migration may have taken.

Ives believes that the people who wore the Promontory moccasins were some of these exact travelers.

“I refer to these as nascent Navajo and Apache cultures,” explains Ives. “Their cultures were forming and taking shape; they were ‘becoming.’” Surely, they weren’t quite the same as the Apache and Navajo would be by 1540 when Francisco Vázquez de Coronado came into contact with them. But this very well could be a snapshot of a culture in transition, meeting and bartering with southern, Numic-speaking peoples and incorporating aspects of what they encountered.

The Promontory caves find is so unique in the region, especially for the time period, that archaeologists like Ives refer to the material culture found at similar sites as the “Promontory phase.” Ives’s collaborator, Joel Janetski at BYU, has been studying Promontory Phase sites around the Wasatch Front, especially around Utah Lake outside of Provo. These Utah Lake sites date to a generation or two later than the Promontory caves, and it might be evidence of the Promontory culture moving southward.

Janetski’s work and that of his collaborators provides a large amount of evidence that a new, big game-hunting culture moved into the Great Basin and replaced the Fremont culture living there, starting right around 1300 A.D. As NHMU continues to receive the artifacts uncovered by Ives and Janetski, we will be able to study and share with the public an extraordinary look at the Promontory phase.

Read more about the Promontory culture in This Was the Place: Athabaskans Gambling on a New Life in the South.

NHMU and Dr. Ives would like to thank George and Kumeroa Chournos for their support and hard work in making the Promontory caves available for archaeological research.

1 Cook, E.R., R. Seager, M.A. Cane and D.W. Stahle, 2007: "North American Drought: Reconstructions, Causes, and Consequences." Earth Science Reviews, 81, 93-134.

2 Ives, J.H., D.G. Froese, J.C. Janetski, F. Brock, and C.B. Ramsey, 2014: "A High Resolution Chronology for Steward’s Promontory Culture Collections, Promontory Point, Utah." American Antiquity 79(4):616-637.

Michael Mozdy is a Digital Science Writer for The Natural History Museum of Utah, a part of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. Our mission is to illuminate the natural world and the place of humans within it. In addition to housing outstanding exhibits for the public, NHMU is a research museum. Learn more.