Kachinas: Much More than Collectible Art

Celebrating Native Artists

This article was published in celebration of NHMU's annual Indigenous Art Market & Festival — a vibrant two-day celebration of Native American art and culture. Get updated information about this year's celebration by following the link below.

By Michael Mozdy

Many people admire the beauty and artistry of kachinas, but fewer people realize that authentic kachina figures spring from a deep spiritual tradition and contain rich symbolism.

The Hopi Spiritual Tradition

For more than 2,000 years, Native Americans in the Southwest have prayed to the great spirits like Tawa, the sun spirit, and Masauwu, the spirit of death. Relying on agriculture in this parched land, they often pray for natural blessings like sunshine, rain, and fertile crops. The Pueblo cultures believe that spirit beings called Kachinas (or Katsinas) exist as a way for the great spirits to communicate with them.

A Kachina has three aspects: the supernatural being, the man who dresses as a Kachina for ritual dances (he becomes the spirit), and the kachina figures given to young girls. In the Pueblo cultures, Kachina rites are practiced by the Hopi, Hopi-Tewa and Zuni peoples. Each pueblo has its own set of Kachinas – no one knows how many Kachinas there are, but estimates range from 300 to over 1,000.

The Hopi say that once during a great drought, they heard singing and dancing coming from Nuvatukaya’ovi, also known as the San Francisco Peaks (close to today’s city of Flagstaff). When they investigated, they met these spirit beings called Katsinas, who returned with the Hopi to their villages and taught them various forms of agriculture.

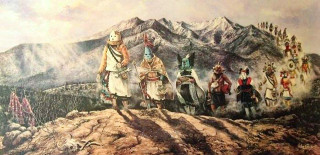

Kachina March by Californian artist John Steele (1921 - 1998).

The Hopi calendar revolves around the Kachina Season, which begins on the winter solstice. They believe that this marks the time of year when Kachina spirits come down from the mountains and live in the Hopi villages. Six and a half months later, they celebrate the Going Home ceremony, which ends the Kachina season with an outdoor Kachina Dance. This is the time when Kachina dancers bring harvest gifts for the spectators and kachina figures for the young girls. Men portray both the male and female spirits and when an initiate wears the mask of his Kachina, he becomes that spirit personified.

Kachina figures, then, represent the spiritual beings who help the Pueblo cultures survive. They are specifically used to teach young girls about how the spiritual and natural worlds are connected. Rather than being simple playthings, kachina figures are usually hung on walls or displayed proudly in the home. They are passed down from generation to generation, staying in families for many decades.

The Art and Craft of Kachina Figures

Although Kachina figures have been found on rock art as early as 1350 CE1 and flat figures are found in the archaeological record, the crafting of kachina figures for sale and trade with communities outside Puebloan society is relatively recent, dating back to the mid-1800s. Traditionally, kachina figures are carved only from the roots of Cottonwood trees.

There are four generally accepted forms of kachina figures:

- Putsqatihu – simple, flat figures made for infants. These are thought to be the oldest type of carved kachina figures.

- Putstihu taywa’yla – generally meant for toddlers, these figures have flat bodies and three-dimensional faces.

- Muringputihu – these figures have cylindrical bodies and fully carved heads.

- Tithu – these are full-bodied kachina figures given to Hopi girls aged two and up at Hopi ceremonies. These are what most people think of as “kachina dolls.”

The most noticeable features of Kachinas are their colors and their regalia, both of which help to identify the spirit and symbolize various things. For instance, the color black symbolizes Nadir, or the underworld, while all of the colors together symbolize Zenith (heaven). Animal tracks, bird tracks, celestial symbols, and vegetable symbols represent those particular spirits (for example, the bear Kachina has two bear footprints on his face). A pair of vertical lines under the eyes symbolizes a warrior’s footprints, an inverted “V” signifies certain kachina officials, and phallic symbols represent fertility, among many other symbols.

Drawings of kachina figures, Plate 11 from an 1894 anthropology book Dolls of the Tusayan Indians by Jesse Walter Fewkes. Public domain.

The regalia often includes accessories that indicate the spirit’s actions. For example, Cold-Bringing Woman carries a sifter basket of snow and scatters it encouraging moisture in the form of snow for bountiful crops. Other accessories include hand rattles made from gourds, bows and arrows, branches of Douglas fir, swords, staffs, scissors, and colored corn.

“Kachina figures are precious works of art,” asserts Glenna Nielsen-Grimm, PhD, NHMU’s Anthropology Collections Manager, “and each carved figure is a unique expression of an important religious and cultural heritage.”

Celebrating the Past, Present, and Future of Kachinas

Today, Native American artists retain the spiritual and symbolic content of kachina figures while pushing the boundaries of the craft and artistry. Authentic kachina figures are highly prized by collectors and fetch thousands of dollars when sold. Unfortunately, there is also a thriving trade in mass-produced figures and even ones made abroad that have little-to-no value but are passed off as kachina “dolls.”

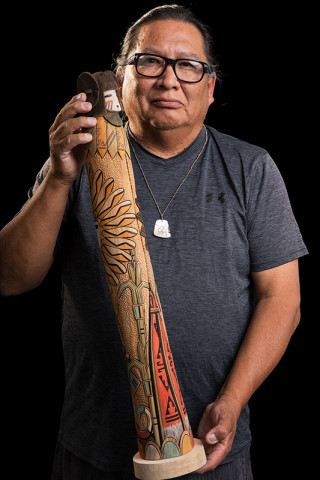

©Mark Johnston | NHMU

The Natural History Museum of Utah strives to recognize the important cultural and artistic work of contemporary Hopi artists. Since 2013, NHMU has hosted an annual Indigenous Art Market & Festival that attracts some of the country’s most talented Native American artists to Salt Lake City. More than 25 tribes have been represented over the years, bringing a wonderful diversity of traditional and contemporary Native American art that is available for purchase. Hopi kachina figure carvers are some of the artists who bring their work to the Indigenous Art Market & Festival.

The museum’s mission also includes preserving and displaying kachina figures that have been gifted to NHMU by private collectors or purchased from tribal artists and families. “Kachinas are an art form, educational items for Native families, and religious items,” says Alexandra Greenwald, Ph.D., NHMU’s Curator of Ethnography. NHMU houses a collection of kachina figures from a range of historical time periods, including the present. “Alongside other aspects of the material culture from peoples in the American Southwest, kachinas provide an important window into Puebloan culture, beliefs, and practices, which is invaluable for all of us to learn from,” she adds.

1 Robert Layton (2012). "Rock art, identity and indigeneity". In McDonald, Jo; Veth, Peter (eds.). A Companion to Rock Art. Wiley. p. 448. ISBN 978-1444334241.