A Utah Fossil's Journey from Evidence Locker to Harvard

By Dan Potter

The 500-million-year-old fossil doesn’t stick out in Carrie Levitt-Bussian’s memory. Why would it? It looks like an unassuming, light gray, palm-sized rock with a thick “Y” on it.

Megasiphon thylakos.

That “Y” is, in fact, an animal—the ancestor of a modern sea squirt. It’s much older than any such relative previously found in the fossil record, and also much better preserved. If you’re into the grand story of evolution and, say, insights into the earliest days of vertebrates, this is remarkable enough to warrant a nine-page writeup by a team from Harvard University in Nature Communications. We’ll get to that.

But Levitt-Bussian has handled thousands of fossils—from ancient footprints to prehistoric poop to spectacular dinosaur skulls; her favorites are the ceratopsians, like triceratops. And what sticks out about this fossil has more to do with how it arrived in her custody, and how it left.

As the paleontology collections manager for the Natural History Museum of Utah, “I am a librarian, but for fossils,” she says. Boxes of rocks come and go all the time. Usually, though, the new arrivals don’t look like they were seized as evidence of a crime.

“There was Customs tape—red, scary tape all over the boxes,” she recalls. (“EVIDENCE,” some of the tape sternly warned: “DO NOT OPEN.”)

Here’s the backstory: Federal law enforcers had seized a large collection of fossils from the Cambrian period, roughly twice as old as the oldest dinosaur. These weren’t common trilobites like the casual, law-abiding collector might pay a few bucks to take home from a roadside quarry. They were amazing finds, many from federal land. The people who illegally took them had some knowledge of what to look for and hoped to sell them in Canada.

So for a long while, these ill-gotten Cambrian fossils were part of a case involving the Bureau of Land Management. Then came the question of where they should end up.

“We’re the state repository for the state of Utah,” Levitt-Bussian says, meaning the Museum is the final home for scientifically significant specimens found on state land. Hence the delivery she received of 2,260 Cambrian fossils in boxes wrapped in red U.S. Customs and Border Protection tape—including that small rock with the thick “Y” on it.

Levitt-Bussian didn’t yet know what she had: “I’m not a Cambrian expert,” she says. But she knew she needed to add these fossils to the Museum’s vast collection, which now stands at some 65 thousand specimens. Each new one gets photographed, numbered using an archival pen on a stripe of white paint, and added to a database so Levitt-Bussian can know exactly what row, cabinet, and drawer to find it in. A system of codes delineates vertebrate and invertebrate paleontology, paleobotany, and ichnology, or trace fossils. (That last category, Levitt-Bussian says, includes snail trails: “Even raindrops can fossilize.”)

Processing new specimens is slow work. Some also require a gentle cleaning using water and a toothbrush. Here, Levitt-Bussian gives a shoutout to Randy and Ann Johnson, two longtime NHMU volunteers who “did a ton of grunt work processing this collection.” The Bureau of Land Management kicked in some funding to help.

“If I had my way, I would’ve been able to curate the entire collection before we offered anything on loan,” Levitt-Bussian says. But that’s not how things worked out.

“Like Kids in a Candy Shop”

Utah is one of the best places on Earth to look far into the geological past to study the Cambrian explosion—a time starting around 540 million years ago when evolution suddenly took a turn for the weird. It’s when a wide variety of animal body plans first appears in the fossil record, many still recognizable today, like the Y-shaped sea squirt.

While the state might be better known for its dinosaurs, it’s a world-class destination for Cambrian researchers like Dr. Rudy Lerosey-Aubril of Harvard: “People don’t realize that Utah is extremely important for the study of these ancient animals,” he says.

Lerosey-Aubril was at the Museum before Levitt-Bussian could even finish unpacking the new collection. He and his Harvard colleague and frequent co-author, Dr. Javier Ortega-Hernández, spent days going through boxes and taking pictures. “This really felt like opening Christmas presents the whole day, which was super cool,” he says.

“They were like kids in a candy shop,” Levitt-Bussian jokes.

Among the specimens that caught Lerosey-Aubril’s eye was the light gray rock with the thick “Y.” “I think we identified this as a tunicate as soon as we saw it,” he says. Tunicates are marine invertebrates that tend to be barrel-shaped and have two siphons, drawing water in and out to catch food in a kind of filter. The resemblance between this one from 500 million years ago and one you might see in the ocean today is striking.

So impressed were Lerosey-Aubril and Ortega-Hernández by this specimen that they asked to take it and numerous other fossils back to Harvard for further study right away. Normally, Levitt-Bussian carefully packs and FedExes such loans, but these went on the flight as carry-on luggage. Lerosey-Aubril says they almost bought another suitcase for the occasion.

“Evolutionarily Significant”

The first line of the Nature Communications paper Lerosey-Aubril authored about the sea squirt, along with Ortega-Hernández and two others from Harvard, describes tunicates as “evolutionarily significant” because their relationship to vertebrates makes them “key to unraveling our own deep time origin.” They named this one Megasiphon thylakos.

“The significance of this paper is to have a fossil report of this animal, and to show that they are so complex, so early,” Lerosey-Aubril says. Indeed, the team was able to make out anatomical details down to the tunicate’s muscles, which is exceptional: While hard animal parts like shells, bones, and teeth tend to fossilize well, this type of soft-tissue preservation is exceedingly rare.

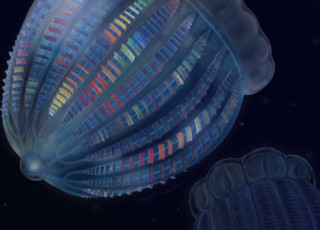

Artistic reconstruction of Megasiphon thylakos and comparisons with modern tunicates.

Artwork by Franz Anthony.

It’s also one reason the Harvard-based group keeps coming back to what Lerosey-Aubril calls “the paleontological greatness of western Utah.” That they enjoy a “particularly fruitful collaboration” with the Natural History Museum of Utah doesn’t hurt, either. The paper on Megasiphon thylakos wasn’t the first result of that relationship—or even the first to come out of the BLM collection.

“There will be papers published on this collection for decades to come,” says Dr. Randy Irmis, curator of paleontology at the Museum and an associate professor at the University of Utah’s Department of Geology & Geophysics. He says Utah’s House Range, southwest of Salt Lake City, happens to be a really sweet spot for this type of work.

“What’s really amazing about Utah is we don’t have just one deposit with soft-body preservation, we have three different deposits: the Marjum, the Weeks, and the Wheeler. All three of those formations in western Utah have all this amazing soft-body preservation with a high diversity of many different animals,” often easily accessible near the surface, Irmis says.

“I’m biased, but I think it’s the best single place in the world to study the Cambrian explosion,” he laughs.

And this underscores the significance of the Museum’s role as the state repository: It’s the clearinghouse for so many of those intriguing fossils. When the Harvard team is done studying a specimen like the Y-shaped sea squirt, it heads back to Levitt-Bussian to find room for it in the Museum’s collection—at least until some other researcher asks her to ship it their way.