Dreaming of Stegosaur Mysteries with Dr. Susannah Maidment

Note: Dr. Susannah Maidment will be a keynote speaker at NHMU's DinoFest: Damage & Defense on January 27-28, 2024. Learn more and prebook DinoFest tickets here.

By Dan Potter

“This is a true story. It doesn’t sound like a true story, but it is,” Dr. Susannah Maidment begins. The paleontologist and world-renowned expert on stegosaurs, now based out of London’s Natural History Museum, was thinking back on her childhood.

She was six or seven, and her grandfather, an electrical engineer, had a question for her: What did she want to be when she grew up? Maidment was, like many kids, into dinosaurs, and says her idea of the work of scientists involved wearing a lab coat and pouring chemicals into beakers and watching them change color.

“That’s what I thought scientists were, and I said I’m going to be a scientist. Or maybe… a princess. And he was very, very keen to steer me toward that scientist route,” Maidment says. The question then became what sort of scientist—something she hadn’t considered. “So, he said, well, why don’t you be a dinosaur scientist since you like dinosaurs so much?” It was settled. “All right then, sounds good. So that’s what I did.”

Susannah, left, and her brother Tom on the beach in England. Image courtesy of Susannah Maidment.

Growing up, Maidment regularly visited England’s Jurassic Coast, a UNESCO World Heritage site known for its spiral-shelled ammonite fossils, as well as marine reptiles. It’s where, some 200 years ago, the pathbreaking paleontologist and fossil collector Mary Anning made a series of momentous finds, including spectacular ichthyosaur and plesiosaur fossils.

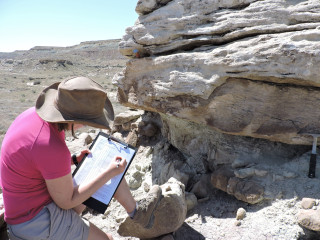

Maidment’s journey as a scientist eventually led her to a doctorate at the University of Cambridge, fieldwork in Montana, and a stint in Vietnam. When she arrives in Salt Lake City later this month, to give a keynote at the Natural History Museum of Utah’s two-day DinoFest event, it won’t be her first time here, either. She’s done a fair bit of work around Utah and the multistate Jurassic playground known as the Morrison Formation, and says it has certain geologic advantages over, say, Southern England.

Both have rocks of the appropriate age, but you’d prefer they be easily visible at the surface.

“And of course, much of Utah is desert—it has a very dry and arid climate. And that means that it’s not all covered with trees and houses and vegetation, which is a problem that we have here in Southern England," Maidment says, "...whereas in Utah, you don’t have to walk very far to see rock on the surface of the earth, and that’s when we can find fossils really easily."

The enigmatic stegosaur

Maidment wound up focusing on stegosaurs partly because that was the open lane when an awkward hiccup in how Ph.D. projects were assigned forced her to change course. After a supervisor suggested it, “I thought, well, I had an inflatable stegosaur when I was a kid, and I had a stegosaur moneybox. Yeah, let’s do it—why not?” (Disclosure: The person writing this piece has a stegosaur tattoo and sees nothing wrong with this decision.)

As research subjects go, stegosaurs do not make life easy for scientists like Maidment. Their fossils are rare and tend to turn up on the scuffed side, even by dinosaur standards. “They’re 150 million years old, plus or minus 30 million years.” Put another way, they predate the evolution of flowering plants, including grasses.

Susannah takes notes while conducting fieldwork. Image courtesy of Susannah Maidment.

“They’re late Jurassic in age, primarily. And that means that they were already fossils by the time T.rex was living and Triceratops was living.” Those two winked out of the fossil record some 66 million years ago, but being from twice as far back in time, stegosaur fossils have been battered by tens of millions of years of additional tectonic cruelties. “So, they’re just not that well preserved.” For whatever reason, their skulls are particularly rare.

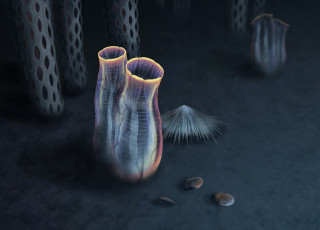

Absent an abundance of easy-to-interpret evidence, mysteries abound—for instance, what was the purpose of those awesome plates that make stegosaurs so recognizable? If they were to help ward off predators, they’re curious in part because stegosaurs descended from dinosaurs with more armor, not less. (Their ancestors were also bipedal, hence stegosaurs’ shorter forelimbs.) But those plates can’t have been for nothing.

“Often in nature, when we see these things that don’t have obvious functions, it would have been incredibly metabolically expensive for these animals to be producing all this bone and keratin and pumping blood to these plates, so they were doing something with them for sure, and that something must have been very, very important to them,” Maidment says.

She suspects they were for display—not so much defensive armor as “a more passive defensive structure.” Some researchers have suggested plant-eating stegosaurs could’ve pumped blood to their plates to send a don’t-mess-with-me message to hungry predators like Allosaurus, but “it’s completely untestable,” Maidment says. “There’s always going to be just-so stories.” The plates may well have had more than one function, too—dissipating heat, perhaps.

Damage and defense: Enter the thagomizer

The other main way stegosaurs protected themselves was with a set of tail spikes known in certain circles as a thagomizer. The word comes from a 1982 edition of Gary Larson’s “The Far Side” comic in which a caveman lecturer pointing to an illustration of a stegosaur’s tail spikes tells those listening, “Now this end is called the thagomizer… after the late Thag Simmons.”

Maidment doesn’t love this word, saying while it’s a funny joke, paleontology already has more than enough jargon. In her view, “tail spikes” will do just fine.

Susannah operates a jackhammer while conducting fieldwork. Image courtesy of Susannah Maidment.

When it came to battling predators, she doubts stegosaurs or predators like allosaurs were exactly nimble. Think less of a gazelle elegantly dodging a lion and more of a clunky ambush. “These things were not running around,” she says. What they were doing, it seems, was flicking their tail spikes, each of which could’ve been two or three feet long.

“People have modeled the swing of those spikes and have shown that the forces that they could have generated on the end of those spikes would have impacted bone,” Maidment says. In fact, NHMU’s paleontology collection includes an Allosaurus vertebra with a hole that suggests that’s exactly what happened to an unlucky predator.

A last puzzling note on defense: A few stegosaur specimens have bony armor on their throat called gular ossicles. (What were we just saying about paleontology being overstocked on jargon?) Describing these tiny fossils as “pebble-like,” Maidment says “it’s easy to imagine that if you were excavating one of these things, you might miss those, because they probably dissociate very quickly and just sort of scatter.”

So why do these appear on some specimens and not others? “It could be that we’ve got different species. It could have been a male and female thing. We don’t know… They’re a bit weird, those.”

Dreams of questions and answers

In her Ph.D. days, Maidment says she used to close her eyes and see stegosaurs. She still sometimes has dreams about fossils, but even then, the dinosaurs keep their secrets.

And the fossil record has so far been vexingly withholding when it comes to stegosaur eggs. Such a discovery would be a scientific boon, Maidment says. “I’d love to find a stegosaur nest… and see how they change as they grow up. Did the babies have plates, for example?”

She’d also love to understand how those plates might differ between males and females—which would go a long way toward clarifying what they were for.

Dr. Maidment at DinoFest 2024

Learn more about Dr. Maidment’s fascinating research into stegosaurs during her upcoming lecture at NHMU’s DinoFest, happening January 27–28 at the Museum in Salt Lake City.