The Life & Work of Dr. Jane Goodall

This article was published during the run of Becoming Jane, a special exhibition that is now closed at NHMU. Learn more about our current exhibitions here.

By Matt Pacenza

The sweep of Dr. Jane Goodall’s life is not just one of extraordinary influence -- on science, habitat protection, environmental education, and activism -- but also one of remarkable transformation.

Goodall, who will turn 90 in April, is featured in the new special exhibit at the Natural History Museum of Utah, Becoming Jane: The Evolution of Dr. Jane Goodall, which showcases not just her groundbreaking work studying chimpanzees in Tanzania in the 1960s, but her decades-long commitment to education and activism.

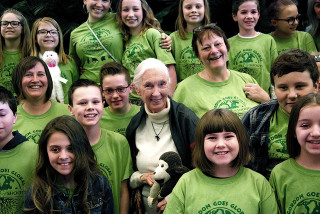

It is no exaggeration to say that Goodall has inspired millions around the globe, a number that will surely grow as Utahns young and old have the opportunity to learn more about her at NHMU’s exhibit. The youth action organization she founded in 1991, Roots & Shoots, has 12,000 active groups in more than 60 countries, and nearly 1.5 million young people took part in its programs in 2022 alone.

One compelling way to learn more about Goodall’s life is at the new exhibition, Becoming Jane, at NHMU. Additionally, two award-winning documentaries cover her remarkable journey. Jane, from 2017, uses newly uncovered footage from the 1960s and 70s to show her early work with chimpanzees, while Jane Goodall: The Hope, from 2020, portrays her life today.

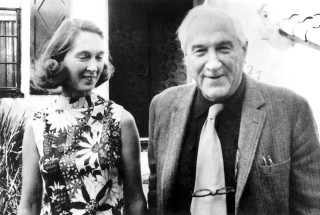

Jane Goodall and Louis Leakey. Image by Joan Travis / JGI

Born in London in 1934, Goodall’s love of animals led her to take a position as a secretary to famed Kenyan paleoanthropologist Louis Leakey in 1957. By 1960, Leakey -- eager to learn more about primates to deepen his study of early humans -- had sent Goodall, then 26, to Gombe, in northwestern Tanzania.

At first, Goodall struggled. The chimpanzees were wary, and she could only watch them from afar. As explained in the Becoming Jane exhibition, after weeks without luck Jane adopted a new tactic to view them from a nearby peak using a spotting scope. As quoted in the exhibit, Jane said “Everything I learned about the chimpanzees was new and surprising, especially how like us they were.”

Chimpanzee mother with infant. Image by Nick Riley / JGI

After months, the chimpanzees slowly began to tolerate Goodall’s presence and soon, she was able to observe closely enough to record the detailed impressions that would form the basis of her ground-breaking research. In one breakthrough, a mother chimpanzee, “Flo,” allowed her baby, “Flint,” to approach Jane, a moment that was captured in a now iconic photograph of the two reaching for one another, featured prominently in the exhibition.

What Goodall learned, and what she taught the rest of the world, was that these chimpanzees were thinking, reasoning members of complex communities. Like humans, they were capable of “joy and sorrow; fear and jealousy,” she says in the documentary.

She also discovered that chimpanzees could make, manipulate, and use tools. They would fashion twigs to carefully remove termites from their underground colonies. Until then, the scientific community believed only humans could perform such feats.

Jane Goodall observes chimpanzees from afar using binoculars. Image by Hugo van Lawick / JGI

Goodall’s early research, showcased in the exhibition and films, is vastly different from contemporary studies of wild animals. Goodall and her fellow researchers (she was soon joined by several students and cameraman Hugo van Lawick) fed and interacted with the wild animals, practices that would be frowned upon today. A letter from van Lawick featured in the exhibition speaks of regular visits made by the chimpanzees to Jane’s camp, sometimes taking food right from her hand. (Note: Dr. Goodall and the Jane Goodall Institute do not endorse handling or proximity to wildlife. This recollection reflects a historical context.)

Nonetheless, the footage of young Goodall holding, playing with and grooming baby chimps is, to use a scientific term, very, very cute. Early media coverage of Goodall, demonstrating the sexism of the era, raved about her beauty as much as her scientific discoveries.

Goodall’s life took its first significant turn in 1964 when she married van Lawick. In 1967, she gave birth to her one child, Hugo, nicknamed “Grub” from an early age. Parenting made research more challenging, but Goodall credits her observations of chimpanzees with making her a better mother, and with being a mother for helping her better understand chimpanzees.

By the late 1960s, domestic demands had pulled Goodall away from Gombe, although research there continued (as it does to this day). The young family spent Grub’s early years in the Serengeti, where van Lawick, a celebrated photographer and videographer, recorded the region’s wildlife, footage captured in Jane.

The couple began to drift apart as Goodall remained connected to Gombe, while van Lawick was drawn to the Serengeti, and they divorced in 1974. And, for the next decade, Goodall balanced her family life with her work as a researcher. (A second marriage to Derek Bryceson, the director of Tanzania's national parks, ended sadly in 1980 when he died of cancer.)

Goodall’s research in Gombe progressed throughout the 1960s and ‘70s when she established the Gombe Stream Research Center and the Jane Goodall Institute, which with National Geographic produced the Becoming Jane exhibition. She published scholarly articles and books, many of which have been translated into dozens of languages to help spread her message of hope throughout the world.

The next major transformation in Goodall's life came at a scientific conference in 1986 where Goodall learned of the increasing threats faced by chimpanzees across Africa. At that time, the global chimpanzee population had plummeted from 2 million to approximately 200,000. Urbanization, deforestation and population growth that were sweeping the planet were drastically reducing the primates’ habitats.

Until that meeting, Goodall says in The Hope, she had chosen to “dodge” controversies. But, she left that conference as "an activist.” In that moment she resolved to commit her life to activism, and has done so up until now nearing her 90th birthday, never once spending more than three weeks in one location and traveling nearly 300 days a year!

Jane Goodall greets a large audience at a public speaking event. Image by Catalin Mitrache / JGI

“Trying to save the world, it’s a bit of a tough job,” Goodall observes in The Hope. It shows her constant journey, at the time in her mid 80s, going from airport to hotel to lecture hall. We see Goodall preparing her own breakfast in hotel rooms, including making toast with a curling iron. Time with her precious grandchildren (Grub’s kids) is also limited, with opportunities to see them happening only once or twice per year.

In activism, Goodall has expanded her scope to do everything she could to help the animals, at times making agreements with non-traditional allies. For example, in 1992, the Jane Goodall Institute established the 27-square-mile Tchimpounga Sanctuary for primates in the Republic of the Congo, which was funded by Conoco, the global energy giant.

In another scene in The Hope, we see Goodall engage with medical researchers in a lab where chimps are being clearly mistreated. Despite conditions that must have appalled her, she calmly addresses them. “If you don’t talk to people, how can you expect them to change?” she asks.

That paid off. By 2015, the National Institutes of Health had ended research on the last federally-owned chimpanzees.

While advocating over the decades, the once-shy scientist blossomed into one of the most powerful voices in wildlife conservation. No longer shy to speak out, Goodall states, “The least I can do is speak out for those who cannot speak for themselves.” This is made clear in a collage of images in the Becoming Jane exhibit where Goodall confronts abuse of chimpanzees in person, from streets and zoos in the Congo to destinations far from the animals’ natural habitats, like the Canary Islands.

The work that Dr. Goodall has spawned is sprawling and immense today. In addition to the ongoing research in Tanzania, the sanctuary in the Congo, the global speaking tour, and the massive environmental educational efforts, the institute that bears her name also funds projects in rural African communities, seeking to not just preserve endangered lands, but to help local villagers.

She has learned, she says in The Hope, that the fates of humanity and nature are intertwined. “It’s useless trying to save chimps by carving out a piece of land and keeping the people off,” she says.

Jane with Roots and Shoots. Image by Mary Paris / JGI

It’s clear that, whatever her many successes, Goodall draws energy today from the many children she interacts with, at her public speaking events, at the Roots & Shoots programs she visits, and in the villages where her institute funds projects As explained in Becoming Jane, “Once [young people] understand the problems facing the plant and are empowered to discuss and act upon solutions, they can do incredible things. Across the world, young people are leading the fight for social change.”

And they’re doing so thanks in part to the incredible inspiration of the likes of Dr. Jane Goodall.

Learn more about Jane Goodall's life story and her ongoing work in Becoming Jane: The Evolution of Dr. Jane Goodall, a special exhibition open at NHMU through May 27, 2024.