Early Stages of Plant Domestication Detected in Utah’s Distant Past

By Mark Johnston & Lisa Potter

This month, researchers at the Natural History Museum of Utah and Red Butte Garden published new findings on the Four Corners Potato, first uncovered by scientists in Escalante in 2013. In their ongoing analysis of the potato, Solanum jamesii, Drs. Lisbeth Louderback and Bruce Pavlik, along with fellow researchers from the University of Wisconsin, used genetic analysis to reveal where the tubers originated before being transported across the Colorado Plateau. Their new findings support the team’s earlier assertion that the potato is a “lost sister” of the “three sisters” of indigenously cultivated food in the region, including maize, beans, and squash.

The genetic research also extends their 2021 findings from Bears Ears in which ancient gardens were found around archaeological sites. These “archaeo-ecosystems” frequently featured plant populations that are still used in present-day Indigenous communities that trace their ancestry to, or currently reside in the same region. Of the many plants surveyed in 2021, 31 were considered rare in the region, and a small potato, now the Four Corners Potato, garnered particular attention as a native species that had been cultivated by early inhabitants of what is now southeast Utah.

“This is one of the rare times in the archaeological record where people invested in native species and brought them to their habitations,” said Dr. Bruce Pavlik, the lead author of the study.

S. Jamesii is a hearty potato that boasts twice the protein, calcium, magnesium, and iron content of an organic red potato. A single tuber of the nutritious crop could yield up to 600 small tubers in just four months. The potato’s “non-archaeological” or native populations are found along the Mogollon Rim of southcentral Arizona and central New Mexico, where it thrives in conifer woodlands and grows in abundance. In contrast, “archaeological populations” of the potato occur within 300 meters of ancient habitation sites and tend to be smaller than the wilder populations.

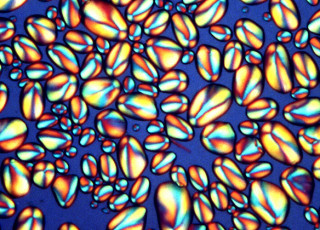

Solanum jamesii plant, the Four Corners potato Photo by Tim Lee

To reproduce sexually and produce viable seeds, flowers need pollen from another plant with compatible genetics. Without this, they clone themselves by sprouting from underground stems, creating genetically identical plants. This cloning ability allows S. jamesii to thrive even in unfavorable conditions and leaves a genetic signature indicating the origin of each population. This signature is often found in potatoes taken to areas with few other individuals and can last for hundreds of generations.

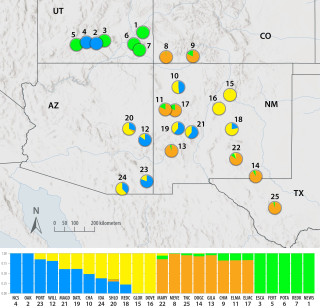

Louderback and her team collected DNA samples from 682 individual potato plants across 25 populations, 14 from archaeological sites and 11 from distant locations in its natural distribution. The results showed that the most genetically diverse populations of S. jamesii were concentrated around the Mogollon Rim. Conversely, populations from archaeological sites lacked genetic diversity because the transported tubers only contained a fraction of the available genes. These findings indicate that the potato was transported and cultivated, likely by the ancestors of modern Pueblo (Hopi, Zuni, Tewa, Zia), Diné, Southern Paiute, and Apache tribes.

Map showing genetic structure by ancestry. Each bar represents the genetic composition of a given potato population and shows where the genes came from. Image by PAVLIK ET AL. AMJBOTANY

Tracing the genetic signature of archaeological populations of S. jamesii found in Escalante Valley in Southern Utah have two different origins: one directly from the Mogollon Rim region and one related to Bears Ears, Mesa Verde and El Morro. These archaeological sites form a genetic corridor suggesting ancient people transported the tubers south to north.

The four sites that Louderback studied around Escalante Valley showed distinct and distant origins of S. jamesii, suggesting that people transported the potatoes to new locations multiple times in the distant past. All this supports the argument that S. jamesii was in the early stages of domestication by ancient cultures.

Alastair Lee Bitsóí, Diné, holds a harvest of Four Corners Potatoes in a Diné Basket at his farm in the Navajo Nation. Photo by Alastair Lee Bitsóí

“Transport is one of the early crucial steps in the domestication of native plants into crops," Louderback said. “Domestication of a plant species can begin with people gathering and replanting propagules in a new location.”

While its origins are now better understood, there is still much to learn about the Four Corners potato. The research team will now look for specific genetic markers for certain desirable traits to better understand if Indigenous people were preferring certain traits in their cultivation of the crop, thus encouraging favorable genes.

Interested in learning more? Read about the ecological legacy of Bears Ears in this related article.