Echoes of Extinction: Conservation Lessons from Tanzania

By Cosette Reeves

Amid the lush tropical forests of Tanzania’s Usambara Mountains—a biodiversity hotspot teeming with species found nowhere else on Earth—life is unravelling. The impacts of forest fragmentation and climate change are disrupting the delicate balance of this landscape, threatening its unique inhabitants. Sadly, this is not an isolated case but an echo of a broader issue. Yet, several dedicated individuals, like Dr. Bill Newmark, are working tirelessly to rectify the impacts of human activity and protect these fragile ecosystems.

Despite the heartbreak of witnessing the gradual disappearance of species day by day, Dr. Bill Newmark, a conservation biologist long affiliated with the Natural History Museum of Utah, remains steadfast in his mission to protect what is left. He has been studying the intricate relationship between species loss and landscape structure in Tanzania since 1986, while fostering a lasting legacy for local conservation efforts. Through this work, he has shown that conservation is achievable with targeted, sustainable action, as demonstrated when he and a team of scientists took on a landmark project in a remote valley of south-central Tanzania to protect the Kihansi Spray Toad.

The Kihansi Spray Toad has the smallest geographic range of any toad, living in approximately a single acre of land within the Kihansi Gorge in south-central Tanzania. Image courtesy of Bill Newmark

The Kihansi Spray Toad population was significantly threatened by the development of a newly commissioned hydroelectric dam, which would bring electricity to hundreds in a country where approximately only 10 percent of the population had access to power at the time. Enlisted by the World Bank, the organization that funded the dam’s construction, the team worked to mitigate its environmental impact. They discovered the dam caused an 83 percent reduction in waterfall spray, severely affecting the intricate environment in which these toads rely upon. In response, the team developed a highly engineered recovery program—an artificial spray irrigation system—to mimic the original waterfall spray, and it worked. By 2003, the toad population had fully recovered! However, just three weeks later, the population unexpectedly collapsed again, plummeting from a count of 20,000 to 300. The Kihansi Spray Toad was declared extinct shortly after.

The artificial spray irrigation system was a great success, allowing the toad population to make a full recovery until Chytrid fungus made a sudden appearance. Image courtesy of Bill Newmark

At the time, Chytrid fungus—an incurable fungus hypothesized to have originated from commercial animal trade and that has endangered over 40 percent of all amphibian species today—had only been identified in Australia and Central America but had yet to be seen in Africa. The discovery of its presence in the Kihansi Spray Toad population was the first documented occurrence in the continent. Fortunately, before the species completely collapsed, Dr. Newmark advocated for a captive breeding program to ensure the ongoing safety of these toads, and eventually, the population became one of the largest extinct populations in captivity.

He has worked closely with local partners over the past 10 years to reintroduce the Kihansi Spray Toad and revitalize the species recovery program in the wild, and it set a precedent. As part of this program, Tanzanian scientists were trained in amphibian diseases, diagnostics, and reintroduction biology, and the project has now been fully handed over to those that were trained and the Tanzanian government. This has not only become one of the most highly visible recovery programs for any species in the world but also greatly contributed to the growth of the country’s conservation biology capacity—a long-held commitment of its people.

Dr. Newmark will soon be writing a book about this experience to share his findings and the implications of the results, but his work in Tanzania continues. For the last 38 years, he has also been studying the long-term impacts of forest fragmentation on understory birds in the Usambara Mountains. Birds are particularly vulnerable to environmental changes, affecting them much more quickly than large mammals and, therefore, enabling us to identify patterns—and potential solutions—much sooner. This project involves studying the long-term history of over 100 species to identify these patterns, and it has become the most comprehensive study ever conducted of an Afrotropical vertebrate community.

Forest fragmentation, as seen here in the East Usambara Mountains, is posing a large threat to species that have flourished for millennia. Image courtesy of Bill Newmark

Through this study, Dr. Newmark discovered the birds not only refuse to cross gaps in fragmented forests caused by human-made developments—leaving these populations isolated and more vulnerable to genetic bottlenecks and health complications—but also now, more than ever, have a greater need to do so. He has begun to observe the compounded impact of climate change on these communities, and it’s creating a perfect storm. As temperatures shift, these environments are becoming uninhabitable to the understory birds, forcing them to move upslope to higher elevations for their survival; however, forest fragmentation is inhibiting them from doing so. As a result, Dr. Newmark is witnessing the decline of every single species he’s studying. Yet, a solution exists: if we can regenerate the forests and close the gaps using natural corridors, starting with the largest and closest forest fragments, these species will have a fighting chance.

Dr. Newmark is repeating the study in western North America parks, this time with a focus on large mammals, and he has identified a similar pattern with habitat isolates. Despite these studies being conducted on opposite ends of the world, the same challenge persists, suggesting that Dr. Newmark’s solution could serve as a model for many other biodiversity hotspots around the globe.

Species are declining worldwide, and the biggest threat is human activity, both direct and indirect, underscoring a powerful truth: we are responsible, and it’s up to us to preserve the essence of our natural heritage. We know what it will take to conserve these species, and it isn’t complicated—nor is it unique—but it demands commitment of several, funds from many, and a deep recognition of the stakes involved by all.

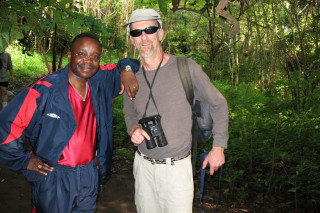

Dr. Bill Newmark has had the privilege of working alongside many Tanzanian locals over the years to develop sustainable solutions and systems to protect the natural world. Image courtesy of Bill Newmark

“If a country as poor as Tanzania is willing to [put the effort in], why aren’t we doing this in North America?” states Dr. Newmark. Despite its developing economy, Tanzania has committed nearly 15 percent of its land to national parks, signed the Convention on Biological Diversity—a legally binding international treaty—and continues to divert precious resources toward protecting its biodiversity. Dr. Newmark desires a similar dedication from the United States and its people. And as the human population and activity in both Tanzania and North America continues to increase, now is the time to act and form protected systems that can be sustained for generations to come.