New Cambrian Fossil from Utah Illuminates Vertebrate Origins

By Eliza Petersen

In Utah's dinosaur-rich geologic landscape, examining a tiny three-quarter inch, long-headed, fossil with no hard parts like bones or teeth may sound a bit modest. But for Harvard paleontologists Dr. Rudy Lerosey-Aubril and Dr. Javier Ortega-Hernández, this 500 million-year-old relic is a crucial clue to a prehistoric mystery: the origin of bone bearing animals, or vertebrates.

Nuucichthys rhynchocephalus, a new fossil species from Utah’s West Desert recently described in the journal Royal Society Open Science, offers a unique glimpse into the evolution of animal life in the Cambrian, a pivotal period in the history of Earth. We had the opportunity to speak with Rudy, the lead scientist behind this groundbreaking research and a NHMU affiliate, to delve deeper into the significance of this discovery.

The Cambrian Explosion of Animal Life

Nuucichthys (Núu-ci), the name Utes give to themselves, and ichthys (fish in Greek), is one of the oldest vertebrate representatives known to science, dating back to the Cambrian Period, about half a billion years ago. This geological period was marked by remarkable biological innovation and diversification in the oceans. "This time interval saw the emergence of animals; that's really the moment when these organisms became prominent components of marine ecosystems," Dr. Lerosey-Aubril explained. Once an inconspicuous life form, animals rapidly diversified during this period, colonizing most marine habitats. Known as the Cambrian Explosion, this event set the stage for the vast diversity of life we see today, and irreversibly revolutionized the functioning of oceans. However, early vertebrates lacked bones or cartilage, making their fossilization and eventual discovery a highly unlikely and thus valuable event.

The sole available specimen of Nuucichthys rhynchocephalus, one of the oldest known vertebrates in the world. The specimen originates from the Cambrian Marjum Formation in the House Range of Utah. Image courtesy of Rudy Lerosey-Aubril

Ancient Yet Surprisingly Complex

Despite its simple appearance, Nuucichthys exhibits several characters that betray its vertebrate affinities. "It is what we call a 'stem group' species, which means that it already possessed some characteristics of modern vertebrates, but not all," Lerosey-Aubril noted. One of the most informative features of this ancient species is its muscle organization. Its arrangement into distinct chevron-shaped muscle blocks is a hallmark of vertebrates and their relatives. Nuucichthysalso had large, complex eyes and a structured branchial cavity. This cavity housed early gill structures and served a dual role in breathing and filtering food. The preservation of such complex features in a Cambrian animal is remarkable, offering unique insights into the anatomical sophistication that characterizes the vertebrate lineage. Yet, Nuucichthys would stand out in an aquarium today, as it noticeably lacks a key characteristic of fish—fins.

A Tale of Two Fossils

The first discovery of a stem-group vertebrate in the western USA improves our understanding of the early history of these animals. Only four similar species were hitherto known: one in Canada, one in the eastern USA, and two in China. "The jury was still out concerning the presence of fins in some of these Cambrian species," the French paleontologist explained. Fins were clearly visible in early fish fossils from China, including Myllokunmingia, but they were conspicuously absent in the North American species. "The fossils of Metaspriggina – a species from the Burgess Shale in Canada and the closest relative of Nuucichthys – do not preserve fins, but they do not preserve the body outline (i.e., the skin) either." Thus, the question remained: were fins originally absent in this species or were they lost during the geological history of the fossils?

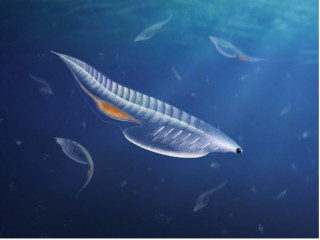

Nuucichthys rhynchocephalus was finless and likely lived near the sea surface, feeding on microplankton. Reconstruction by Franz Anthony | © Harvard University

Most scientists favored the second hypothesis (poor preservation). "People thought, 'Okay, since the skin isn’t visible either, maybe the external features were particularly prone to decay and disappeared before fossilization,'" Lerosey-Aubril elaborated. “But in the new fossil from Utah, the outline of the body is clearly visible under the microscope and stops very close to the muscle blocks. Beyond this line, there is nothing else.” This genuine absence of fins in Nuucichthys and its closest relatives in North America impacts our understanding of these organisms’ lifestyles. “These small early fish were clearly not cruiser-type swimmers; instead, they likely lived in the upper layers of the sea, occasionally using body undulation to reach plankton-rich areas”. This distance to the seafloor, along with the delicate constitution of their bodies, may explain why their remains are only found in a few Cambrian fossil sites renowned for their exquisite preservation—a select group now including the Marjum Formation of Utah.

The Significance of Nuucichthys

The discovery of Nuucichthys provides valuable insights into the early evolution of vertebrates. Through study of this ancient species, scientists can reconstruct the evolutionary steps that led to the complex body plan characterizing the extant representatives of the group. Nuucichthys exhibits surprisingly advanced anatomical features for a 500-million-year-old fish, which highlights the rapid pace of evolutionary innovation during the Cambrian Explosion. The finding of one of our oldest ancestors in Utah’s House Range also underscores the unparalleled significance of the state’s geological record in documenting the dawn of animal life. “Utah is home to an incredible paleontological archive,” Lerosey-Aubril concluded. “The beehive state is renowned for its spectacular dinosaurs, but fewer people know that it is also one of the world’s most important regions for studying the origins of animal life.”

Looking Ahead

BLM-authorized scientific investigations are ongoing in the Cambrian Marjum Formation of the House Range, Millard County, Utah. Image courtesy of Rudy Lerosey-Aubril

Nuucichthys is just one of several thousand Cambrian fossils in the collection of the Natural History Museum of Utah. Harvard-led investigations are also ongoing in the fossil-rich Cambrian layers that yielded this new species. Both sources hold the promise of exciting discoveries from a time long past, when ancestors of vertebrates, arthropods, comb jellies, tunicates, and a myriad of other animals were transforming the oceans into vibrant ecosystems teeming with life.

For more detailed information on this discovery, you can read the full scientific paper published in the open access journal Royal Society Open Science here. The curation of this specimen was supported by the Bureau of Land Management.

Want More Paleontology?

If you enjoyed this article, be sure to check out DinoFest at NHMU, happening the first week in January!