Curiosity Erupts: A Paleoecologist’s Journey from the Field to the Lab

By Cosette Reeves

Science is for the curious—those who seek the truth and find joy in the challenge. For Susan Velasquez-Franco, a first-generation postdoctoral researcher at the University of Utah, her curiosity about science and the natural world took root at the young age of six. Growing up in Colombia, she spent her weekends and school vacations on her family’s coffee farm chasing frogs, bats, and lizards, fascinated by the life surrounding her. Encouraged by her parents to continue to feed this fascination and explore her own beliefs about the world, she credits this freedom as the key to fostering her curiosity and driving her work in paleoecology.

Velasquez-Franco is breaking ceilings as a first-generation student, a Latin American woman in STEM, a paleoecologist, and a postdoctoral researcher in the University of Utah’s School of Environment, Society, and Sustainability (ESS). Now supported by the Natural History Museum of Utah (NHMU) and the University of Utah’s College of Science, she conducts much of her work at the Museum and the College of Science EARTH Core facilities. She’s often working in collaboration with students or Museum colleagues, including Dr. Mitchell Power, Dr. Lynne Zummo, Dr. Randy Irmis, and Dr. Bryn Dentinger, and is involved in several projects across Nevada and Utah. For the last six years, however, she has been primarily focused on expanding her NSF-funded master’s thesis, which explores the environmental and climate history of the volcanic landscapes in the Andes.

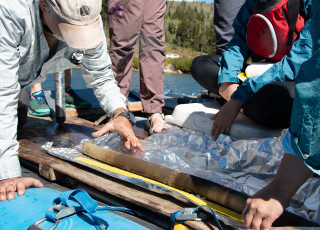

Velasquez-Franco and Dr. Mitchell Power embarked on their first field trip together to Colombia in 2020 to collect sediment cores from the Laguna-Maar de San Diego with the support of University of Utah Center of Latin American Studies. San Diego belongs to the northernmost active volcanic field in South America.

Her research involves collecting sediment cores, or tubes of lake mud, from the field and analyzing them to build a historical record and reveal how climate variability—such as El Niño and La Niña—climate change, and other disturbances like volcanic and human activity shape the trajectories of ecosystems. The study centers on four key volcanic fields within the Central Andes: Laguna-Maar de San Diego, El Tabor Maar, Volcan Cerro Machin, and Laguna Negra.

These sites have been fruitful—each surrounded by a unique and dynamic ecosystem, ranging from cloud forests to tropical dry forests, and each rich with information. By examining both the past and present structure of life in these diverse settings, researchers can identify patterns in how environmental change influences land recovery and organism dispersal over time. These effects can vary significantly across regions. For example, Velasquez-Franco explained how the same climatic event can manifest in vastly different ways: El Niño might look like drought in Colombia but like excessive rain in the southern United States. This highlights the complexity of climate variability and all the factors that can shape its impact throughout history.

Velasquez-Franco works with botanist Julio Sierra-Giraldo from the University of Caldas to sample flowering buds to obtain a pollen reference collection as part of a botanical survey.

These insights are only possible, however, with a solid foundation of current data. Before Velasquez-Franco can delve into the historical records found within these volcanic sites, she must first establish a comprehensive baseline for the life existing there today. This requires completing a detailed botanical baseline, noting the plant and soil diversity and recording as many species present as possible. For Laguna-Maar de San Diego, University of Caldas master’s student Julio Sierra-Giraldo led this work, publishing his findings in the Rodriguésia scientific journal with co-authors Velasquez-Franco, Dr. Mitchell Power, Jairo Andrés Orozco-Agudelo, and Luz Amparo Triana-Moreno. The publication not only documents the region’s rich biodiversity but also advocates for its protection, and Sierra-Giraldo’s thesis earned laureate recognition. Collaborating with students like Sierra-Giraldo is one of Velasquez-Franco’s greatest passions.

Inspiring Curiosity in Students Through Research-Focused Mentorships

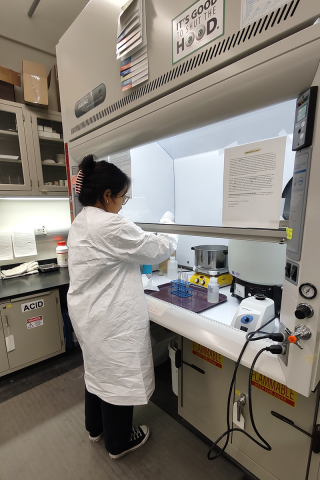

The University’s SRI students are greatly involved in Velasquez-Franco’s lab work — here you can see scholar Jailyn Primero Wilkes preparing Laguna Negra sedimentary samples for pollen analysis, which is just one of the many components to be analyzed from the sediment cores.

Velasquez-Franco has a long history of teaching—a path she never foresaw herself taking when she first earned her bachelor’s in biology from the University of Caldas. However, after being given a series of opportunities to teach K-12 students and work with a wide range of university students during her master’s program in ecology, she discovered a new passion for supporting the next generation of scientists. She now mentors several students, representing a variety of academic disciplines, from both Colombia and Utah, inspiring them to pursue their own curiosities through individual research opportunities and the University of Utah’s Science Research Initiative (SRI) program.

Through the University’s SRI program, Velasquez-Franco provides undergraduates with an early introduction to research, helping them develop a researchers’ mindset and learn to navigate methodologies, theories, and the realities of day-to-day lab work. This hands-on experience is crucial in shaping their understanding of science and its application, and she is deeply committed to providing them with a well-rounded experience both in the field, when possible, and in the lab. “Lots of learning by doing—that’s my preferred way to introduce students to the sciences of the natural world,” states Velasquez-Franco.

Searching for Sedimentary DNA: A Historical Snapshot of Life

Velasquez-Franco and Power brought back thousands of years’ worth of data to analyze from their most recent field trip this past fall, including a sediment core from their first visit to the wetlands of Cerro Machin — one of the most violent volcanoes in South America. The initial analysis of these cores is being funded by the University of Utah’s College of Science.

Having brought many samples back with her from her fieldwork in Colombia this past fall, Velasquez-Franco and her students have been busy in the labs at NHMU and the University’s Geology & Geophysics Department analyzing the cores, employing all the advanced technologies the University makes available. These tools include core logging with a magnetometer, spectrophotometer, pXRF, ICP-MS, and laser diffractometer, all of which produce valuable insights but are best when used collectively. Recognizing the limitations of piecing together biodiversity data from multiple methods, Velasquez-Franco has also begun exploring the possibility of using sedimentary DNA—which offers the potential to provide an all-in-one snapshot of the life that coexisted at different points in history.

She is collaborating with colleagues to assess the feasibility of this method, for while sedimentary DNA promises a wealth of data, it also presents challenges in interpreting the sheer volume of information it could produce. Over the next year, Velasquez-Franco aims to determine if sedimentary DNA could meet the needs of her research. To pursue this, she plans to secure additional funding to return to the field and extract frozen lake cores, which preserve DNA more effectively than standard extraction methods. And there is no doubt she will offer her university students an opportunity to participate in this potentially groundbreaking discovery.