The University of Utah’s Botanical Legacy

By Cosette Reeves

Behind every collection is a collector—a catalyst for discovery. Be it a student, a teacher, a traveler, or simply a curious mind, science as we know it would not exist without them. This inherent human thread allows collections to serve as time capsules, capturing both scientific and cultural shifts and reflecting pivotal moments in our shared history.

By taking a closer look at the collections started by past generations, such as those who helped form the University of Utah, we can gain insight into the people who came before us and begin to see how the act of collecting has long served to connect us across space and time.

A University Takes Root in Utah

The University of Utah’s early roots stretch back to well before Utah gained its statehood in 1896. Shortly after the Latter-Day Saint migrants settled in Salt Lake Valley, the University officially opened its (figurative) doors as the University of Deseret in 1850.

Orson Howard, Professor of Zoology and Botany at the University of Deseret and University of Utah. Digital Public Library of America

Classes were held in private homes and supported solely by private donations. Despite a valiant community effort to keep public education available, the University was forced to close three short years later due to insufficient funding. But the effort didn’t end there.

In 1869, as trade and travel became more prominent in Utah, the University was reopened. The construction of the transcontinental railroad brought in new sources of funding and attracted more potential students, helping to better sustain the program. That year, the University was appointed a president, John R. Park, who took on the challenge of re-establishing the institution with only twelve faculty members.

Many of the original faculty members were not only educators but also active researchers, such as Orson Howard. Howard founded the first herbarium associated with the University in 1874 and laid the foundation for the botanical collection we see at the Natural History Museum of Utah (NHMU) today, seeding its future success. Over time, a legacy took root—one that tells a story not just of plants but of the people whose curiosity, care, and contributions have shaped it.

The Herbarium of Human History

Storytellers by nature, we seek to document and share our experiences, passions, and observations with others. Collections are one way we can do so—revealing where we traveled, what we saw, and what we believed mattered. NHMU’s Garrett Herbarium houses a large, worldwide collection of mistletoes gathered by Del Weins, who spent his career traveling the globe from South America to Africa to Australia, becoming a specialist in this family of flora. It makes you wonder where his passion originated from and why he decided to make this his life’s work. His story, like so many behind the specimens in our collections, reminds us these collections are not just records of the natural world; they are reflections of the people who built them. Because of this, these preserved pieces of the past can contextualize the world more so than words, or even photos, can. They reflect the values, conditions, and events of their time, bearing witness to human history.

Collected by Orson Howard in 1880, this Booth’s Evening Primrose specimen can no longer be found in the Salt Lake Valley.

Alyson Wilkins, NHMU’s Collections Digitization Coordinator, shared a couple of examples she has encountered in her work. The University’s mineral catalog expanded significantly in the 1890s, fueled by Utah’s mining boom. In contract, periods of war brought noticeable dips in collection activity, as many individuals were called into service with the U.S. Army.

The botanical collection, in particular, offers valuable insight into where and how people once lived. Many early specimens were collected near landmarks that no longer exist, along streets whose names and boundaries have since changed, and in environments that have been significantly altered over time. Among them are species that have vanished from the area entirely, such as the Booth’s Evening Primrose, and others that have become exceedingly rare in the area, including the Fringed Loosestrife and American Dragonhead.

In 1912, Salt Lake City’s high school program included a course titled High School Botany, taught by A.O. Garrett — a former botany professor and namesake of NHMU’s Garrett Herbarium. Salt Lake Tribune, 1912

The educational priorities of past generations are also reflected in the collection. Remarkably, many of the earlier specimens in Howard’s original herbarium were gathered by high school students. Botany classes were offered in a few schools across the country throughout the 1800s, but they became more widespread in the early 1900s following the recommendation of the National Educational Association that all high schools offer a full year of botany or zoology (Conover, 2011). Botany classes often involved instruction on plant analysis—collecting and studying local plants, making observations, and properly identifying them using the dichotomous key (Conover, 2011). This science education movement eventually gave rise to the concept of general biology classes, which became the standard in later decades.

Sowing the Seeds of Collaboration

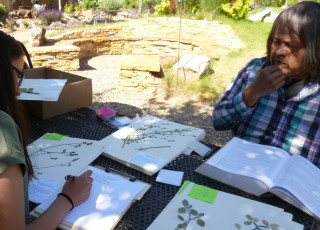

While collections embody key moments in human history, they can also capture moments of humans being… well, human. Botany is a uniquely collaborative science, strongly rooted in the act of sharing. Depending on the abundance of the plant so as not to negatively impact its success, a collector will often gather duplicates — a specimen to keep, one to donate to a local research institution or collection facility, and another (or several) to share with colleagues.

This duplicate specimen, commonly known as Horned Pondweed, was collected in the Alps in 1823 and later shared with the University. The exact country of origin is uncertain, though the collector noted “(?France),” suggesting he believed he was in France at the time. He was clearly guided more by curiosity than by borders.

NHMU holds a few duplicate specimens from Europe that date back to the early 1800s, possibly even earlier. Similarly, samples from Howard’s collections can be found in institutions around the world, including Harvard, Brigham Young University, and the University of Lethbridge in the U.K. Collections rarely exist in isolation — they are often shaped by the contributions of many.

As we look back in time through the lens of specimens documented by Howard and other curators, we can see how often others played a supportive role in their work. Lois Arnow, who wrote Flora of the Central Wasatch Front, Utah—a textbook still used by University field botany students—listed her husband and her two sons as co-collectors on a few of her specimens. They occasionally joined and assisted her in the field. Charles Strevell and his wife built their own museum in the old Lafayette School and dedicated it to the memory of their son. Later, Strevell’s collections were donated to NHMU and became a significant part of the Museum’s early holdings. Science thrives on this shared curiosity and the families, friends, and collaborators who inspire and nurture it.

There are several other examples, and likely many more yet to be discovered. While the Garrett Herbarium’s entire collection has been photographed and displayed online, much of the data remains to be transcribed. Who knows what new stories might be uncovered?

A Botanical Legacy

The story of the University’s botanical collection is not just about plants—it’s about people. Students, scientists, and communities whose curiosity and care continue to connect us across generations, ensuring fewer names are forgotten. Those names lie at heart of the collection’s legacy, a legacy still unfolding as the specimens quietly await the next curious mind to take a closer look.

From the Toronto, Joseph B. Photograph Collection — a group portrait of the first University of Utah faculty.