Digitizing our Herbarium Collection

By Michael Mozdy

From birds to barnacles, beetles to beets, museums around the country are digitizing their collections. Just two of the many good reasons to do this: more people will be able to see and learn from specimens that have been kept out of sight for decades (if not centuries); and when they are fully digitized, often fragile physical specimens can stay better preserved with less handling.

As with any massive undertaking, it’s a bit more complicated than it sounds. Let’s take our herbarium collection, for instance. Here’s a quick walkthrough of the challenge.

Dueling Databases

There are several online biological databases and museum databases in which the information must be stored and shared. When our Herbarium Collections Manager, Elizabeth Johnson, came to NHMU in 2014, we had about 20,000 specimens digitized, “but they were in different databases,” she explains, “so our goal was to centralize the data. Now we use two programs that can both import and export, so we’re set.”

Ever-Increasing Volume

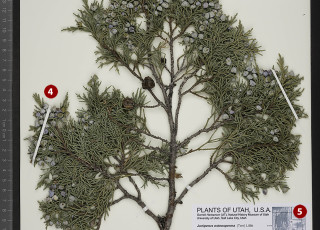

We’ve got 135,000 specimens, each mounted on what we call a herbarium sheet that contains a lot of identification information (read Decoding a Herbarium Sheet to learn more). That’s a lot of database entries. Oh, and then there are the hundreds of unprocessed samples that continue to arrive in between sheets of newspaper and find a home on herbarium sheets in our climate controlled storage cabinets. This is not a job for people who have issues with a backlog of work!

A History of Herbariana

OK, I made up that word, but just like America has Americana, herbaria have centuries’ worth of history on their herbarium sheets. What was written in the late 1800s by a gentleman collector is quite different than what is written today (complete with latitude and longitude location measurements), so we’ve got very different levels of detail. Not to mention some entries in other languages like Portuguese and Spanish.

Move Over Numbers, Here Come Barcodes

Our old cataloguing system was a simple number system. Now, however, bar codes are a great way to reference an entire digital record that can be accessed through a simple scan. So, we’ve got a legion of volunteers helping us pull out each sheet and place a new bar code sticker on it.

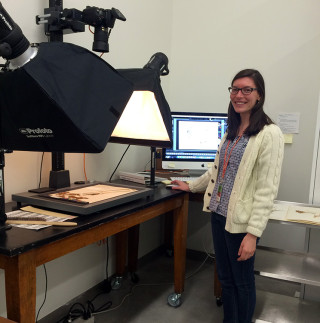

While I’ve Got You, Let’s Get a Picture

“These days, digitization is pretty much synonymous with imaging and databasing,” says Johnson, “so we have an imaging expert taking photos of everything we barcode.” The Herbarium has set up a nifty imaging area where a high-resolution camera and lights help get the job done.

We couldn’t even contemplate this amount of work without our volunteer force, but we also needed to have a staff resource beyond Johnson, whose responsibilities span much more than the digitization project. So, in 2014, a woman by the name of Martha Maezumi became part of our herbarium staff, and she has been working tirelessly for two years doing everything from data entry to barcoding, specimen after specimen after specimen. Martha came to the Herbarium via an indirect route, and her story is an interesting one. Read her story: Our Barcoding Maven: Martha Maezumi.

Michael Mozdy is a Digital Science Writer for The Natural History Museum of Utah, a part of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. Our mission is to illuminate the natural world and the place of humans within it. In addition to housing outstanding exhibits for the public, NHMU is a research museum. Learn more.