Decoding a Herbarium Sheet

By Michael Mozdy

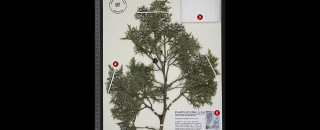

Below is a photograph of an NHMU Garrett Herbarium sheet used as part of our digitization project (read Digitizing our Herbarium Collection to learn more). Once we upload this image to our online databases,scientists and researchers can choose to reference the plant online to save on the wear and tear on the actual specimen. The other information on this herbarium sheet will also be entered into the database. We’ve added the red circles and numbers to help explain the image.

1. The ruler on the left and header at the top provide great reference information for the photo. Clearly, the ruler tells us that this specimen is around 37 cm in height, but more importantly, the juniper berries can be measured at ½ cm, as can other parts of the plant’s morphology. The color palette at the top helps to ensure that true colors are represented, and the logo for the Natural History Museum of Utah’s Garrett Herbarium clearly marks this as one of our specimens.

2. The “UT” in the circle is not just our state abbreviation – in the world of herbaria, it’s the Garrett Herbarium abbreviation (which, if you didn’t know, is our state herbarium). “BRY” is the abbreviation for Brigham Young University’s herbarium, “US” is the Smithsonian’s United States National Herbarium, and some of the earliest herbariums go by just a single letter: “F” is for the Field Museum in Chicago and “K” is the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew, England. Next to the herbarium stamp/abbreviation is one of our new bar codes – every herbarium sheet now has a unique bar code and number to aid in our digitization project.

3. This neatly folded paper packet is glued to the sheet and contains any bits of the specimen (leaves, seeds, stems, etc.) that may have fallen off when affixing it to the sheet and handling it. It is called the fragment packet and researchers can access physical samples of the specimen from this packet rather than taking from the mounted specimen. They can use what’s in the pouch to extract genetic samples and do other research.

4. The white lines across the specimen are thin pieces of paper tape that hold the specimen in place. Much thought goes into the size, shape, and position of the specimen as it is mounted. As you might guess, it also takes a precise and patient person to mount specimens professionally.

5. The lower right corner of the herbarium sheet contains the bulk of the identification information:

-

The header explains that this belongs to a collection of Utah plants, housed at our herbarium in Salt Lake City

-

The next line provides the scientific name, Juniperus osteosperma, as well as the person who first described and named it and (when necessary) the person who later changed the name.

-

The following paragraph explains the location where the specimen was collected. Starting with the county, this sheet explains how far from a nearby town and highway it was found. In addition to this written explanation, a GPS latitude and longitude measurement of the exact location appears next.

-

The large paragraph on this sheet describes in detail the other flora in the area, the habitat, the type of soil, and any human disturbance of the site that may have occurred. When taken in conjunction with the specific location information, this information is very helpful when re-surveying sites in the future to see how plant communities may have changed over time.

-

The bottom of the sheet names the collector and the date of collection, followed by the plant family (Cupressaceae – the cypress family), which is helpful when going through a stack of sheets without having to open them fully.

Herbarium sheets are always kept inside large manila folders to keep the specimens from getting accidentally harmed in any way.

Below is one of our early specimens from 1888 (when we were the University of Deseret!). It’s very enlightening to compare these two sheets to see how our 135,000 specimens in the herbarium contain a fascinating history not just of plants, but also of the habits and techniques of human collectors.

Michael Mozdy is a Digital Science Writer for The Natural History Museum of Utah, a part of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. Our mission is to illuminate the natural world and the place of humans within it. In addition to housing outstanding exhibits for the public, NHMU is a research museum. Learn more.