Human Beginnings on the Colorado Plateau

By Cosette Reeves

Inwardly jumping up and down, Ph.D. candidate Abby Baka found herself in the middle of the San Rafael Desert with a fluted spear point in hand. After weeks of hiking through the relentless heat, finding one felt like a dream come true! It was evidence of human presence during the Pleistocene-Holocene Transition (PHT) period — a time marking the end of the last Ice Age, approximately 11,700 years ago.

The Colorado Plateau’s PHT archaeological record is sparse compared to its surrounding regions: the Great Basin to the west and the Rocky Mountains and Great Plains to the east. So, Abby, joined by a team of colleagues, students, and citizen scientists, set out to uncover why.

Foundations in Stone

Archaeologists often study two primary human lifeways: hunter-gatherers and agriculturalists. While both explore how humans live within their environments, the latter often tends to focus on humans living as members of a stratified society or state — encompassing elements such as social hierarchies, permanent settlements, and organized systems of production. “I want to study people when they’re just being human,” Abby explains. “Hunting and gathering is so much closer to how we evolved to be.” This desire — to understand humanity at its most fundamental level — became a driving force as she pursued her master’s.

Abby’s master’s thesis focused on early Holocene hunter-gatherers at North Creek Shelter — a stratified rock shelter on the Colorado Plateau — where she studied the site’s lithic, or stone, tool technology.

A North Creek Shelter ground stone tool (left) curated at the BYU Museum of Peoples and Cultures and a fluted point chipped stone tool (right) curated at the Edge of the Cedars State Park Museum.

During the PHT, humans used two types of lithic tools: ground stone tools, generally used to process plants, and chipped stone tools, typically used to procure and process animals. By examining the relative investment put into making each tool type, researchers can decipher how humans adapted to their surrounding environment within a theoretical framework known as behavioral ecology. Abby developed a quantitative index to study changes in this technological investment over time, considering factors such as the number of tools found in each category (ground or chipped), the level of craftsmanship, and the raw materials used (high-investment, harder-to-source raw materials or low-investment, local raw materials). She then compared this data to evidence of dietary changes through time, a study conducted by NHMU Curator of Archaeology Dr. Lisbeth Louderback.

Her findings show consistent investment in chipped stone technology that matches a steady consumption of animals, yet her findings also demonstrate increased investment in ground stone technology, which parallels an increase in plant consumption. This observation tells a likely story of a growing community of women — whose primary roles were typically as gatherers — and families at the site, changing dietary priorities in response to ecological shifts, or perhaps both.

This planted the seed for Abby’s dissertation. If these findings could be found in one pocket of the Plateau, could they be found elsewhere too? Or was North Creek Shelter an anomaly?

Traces in the Sand

This map is the result of Abby’s random forest predictive model. The model runs 2,000 decision trees to determine where PHT archaeology is most likely to be found.

The lack of known PHT archeological records on the Colorado Plateau could be due to one or more of the following factors: insufficient research, the area’s geology and climate lending to less-successful preservation of sites and artifacts, or, simply, a low PHT human population. Working with several experts in the University of Utah’s anthropology and geography departments, Abby developed a random forest predictive model for archaeological sites, which works similarly to a species distribution model. This tool predicts which environments are most likely to contain evidence of PHT human presence, and, therefore, where these sites are most likely to be found. The model revealed a large cluster of high-probability areas in the San Rafael Desert.

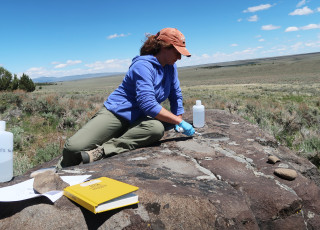

During Abby’s San Rafael Desert survey, several citizen scientists joined the effort. Abby believes it’s important to involve the public in these pursuits, to receive insights from diverse perspectives, and to instill a sense of stewardship within the community for the archaeological record.

Gathering a large group of volunteers, faculty, field school students, and citizen scientists, Abby organized a 35-day survey of the Desert, covering approximately 2400 acres of land. “It seems like you’re looking for a needle in a haystack, but then you actually end up finding stuff!” Abby remarked. They found five PHT artifacts — chipped stone tools — across three sites and one isolate. Found at one of those sites, two distinct spear points suggest possible interactions between neighboring cultures.

This evidence proves that Abby’s random forest predictive model worked and the region’s PHT history is worth studying further. She suspects, although humans did live on the Colorado Plateau during the PHT, there was still a relatively lower population compared to nearby regions. This was likely due to the land’s high aridity and the more appealing ecological variety that could be found next door. Abby will continue to publish on and defend this dissertation until she walks in May.

Unearthing Lessons in the Dust

Abby Baka fell in love with anthropology in second grade during a field trip to the Mitchell Indigenous Archaeological Site in South Dakota, and she’s been pursuing that passion ever since.

Grad school — and the world of academia in general — can be easy to romanticize. The work is fascinating and full of discovery, and the passion driving it is contagious. But for all its wonder, it can be just as unforgiving.

Abby spoke candidly about the toll this work has taken on her mental health. Grad school is financially and emotionally taxing, even with university support. It requires a multi-year commitment to maintain self-motivation and discipline, often without clear progress.

“You can work for years and not find what you want to find. But that becomes its own data,” Abby reflected. That sentiment may be the ultimate metaphor for life: the unexpected is still evidence of progress and a worthy part of the story.

For six years, Abby told herself, “I can always quit tomorrow.” But she never did. Instead, she kept going, making discoveries no one else has made while navigating the constant curveballs of research, life, and self-expectations. Now, she’s close to the finish line.

She shared what helped most was finding hobbies and a community beyond her academic life. Investing in friendships and creative pursuits outside of research reminded her that her worth was not bound to her findings, despite the passion she has for the work.

What the Sand Remembers

Abby is piecing together a story once thought too faint to find — proof that even in the most arid corners of the world, traces of early humanity remain. Perhaps that’s what her own personal journey reflects: even through life’s challenges, a quiet resilience that seems so inherently human can endure.

When you meet a grad student, ask not only about their work but also about what it takes to keep going. Their tenacity and persistence are essential threads of the story, woven into the larger narrative they’re uncovering.