It’s Never Too Late to Starch Again

By Cosette Reeves

Christian Minton screening excavated sediment at the Range Creek Field Station excavation.

Years ago, Christian Minton didn’t know what he wanted to do. He took a five-year break from school, convinced academia just wasn’t for him. But curiosity has a way of resurfacing. When he eventually decided to test the waters by enrolling in a single college course — an archaeological methodology class at Utah Valley University — something clicked. What began as a tentative step forward quickly grew into a passion.

Newly inspired, Christian immersed himself in his education and earned a spot at the esteemed Range Creek Archaeology Field School, where he gained the hands-on training he needed to undertake his own research in the field. Now a University of Utah graduate student, Christian has found the direction he long sought in academia — a pursuit that has since drawn him knee-deep into the search for an improved starch-extraction methodology.

What does starch have to do with archaeology?

Scientists are seeking to uncover the history of our environment: what types of species existed, what disruptions the environment suffered from, and how humans survived it all. Archaeologists strive to decipher the latter, using a variety of methods to piece together past human behavior. Analyzing the pollen, macrofossil remains, and starch left behind among ancient sites, archaeologists can decipher what resources were available at the time and how those who lived there drew upon them.

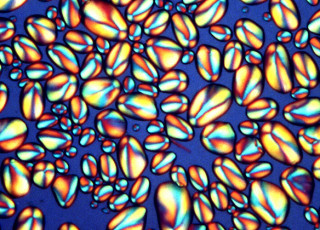

Starch granules in DIC (Direct Image Capture) and polarized. Photo credit belongs to Samantha Annabel Barquero.

Starch is a micro-crystalline structure that plants use to store energy. Commonly found in roots, tubers, and grains, starch residues on ancient artifacts serve as a key indicator of a region’s prehistoric agricultural resources. Given its stable structure and its ability to adhere to surfaces, starch can be remarkably resistant to decomposition. Traces are often preserved on ground stone tools and other implements used to process food.

Christian assisted University of Utah student Samantha Annabel Barquero in testing 50 ground stone tools from Range Creek for such traces. Out in the field, Samantha used a toothbrush sonication method with a deflocculant, a chemical that helps break apart sediment and free trapped starch residue. Each sample was then collected into a test tube and brought back to the lab for further analysis. With Christian’s help, they meticulously scoured the samples under a microscope, devoting two hours to each slide, only to find just a scattering of starch granules. They were surprised by the sparse results.

Christian scans each sample under a microscope, looking for the trademark cross pattern of a starch granule—a feature that distinguishes it from other microscopic plant structures, like pollen or bordered pits.

Shall we starch again?

Range Creek is renowned for housing hundreds of well-preserved prehistoric Fremont sites. Surrounded and composed of BLM, TLA, and private land, the area’s sites are well protected and maintained. Given the depth of history preserved at Range Creek, Christian couldn’t help but believe more starch was there — they just couldn’t see it yet.

Although using a deflocculant is a common method for extracting starch samples, Christian decided to try something different. He collected 14 of the same ground stone tools Samantha had tested and used an ultrasonic cleaning method — akin to what a jewelry might use to clean delicate pieces — to harvest the trapped starch.

A sandstone mano, or ground stone tool, after ultrasonic cleaning.

Yet again, he meticulously scanned each slide under a microscope. After occasionally battling motion sickness while doing so (try spending hours scanning a screen for very specific circles!), Christian identified 77 starch granules — a 15-fold increase compared to the previous analysis. Among his findings were a few species not yet found in Range Creek, potentially allowing researchers to extrapolate new insights into the environment and human behavior of the time.

What might this discovery mean?

“Our current methods may not be representative of all we can find,” Christian explains. If ultrasonic cleaning helps us gather more — or at least more specific — information, we may be able to refine our questions and obtain more concrete results in the future.

It remains unclear why the deflocculant was ineffective in the initial attempt. The issue may stem from a flaw in the methodology itself, or the field conditions at the time may have been inconducive to testing. Christian plans to test the method again. By combining the two approaches — a deflocculant with ultrasonic cleaning — he may develop an improved method for starch collection that yields more reliable results.

Over the next several months, Christian will continue this work, assessing whether repeated testing reveals additional findings, and if so, whether the differences are significant enough to draw a conclusive conclusion.