Why are There so Many Wildfires Right now?

Understanding fire is an important part of reading Utah's landscapes. Credit: Riley Black

By Riley Black

Some days this past summer, you could step outside and smell the smoke. Wildfires in Utah, as well as major blazes in California, scented the air and tinted the sunsets red. Despite the headline-making conflagrations, though, how can we tell if 2020's fires were really more frequent than in times past?

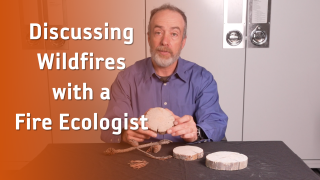

The answer, says the Museum's Garrett Herbarium Curator Mitch Power, relies upon how researchers collect and compare wildfire data spanning decades, centuries, and millenia. Depending on the chosen frame of reference and what data are used, the answer might vary. "Things might seem to be different than they were several decades ago," Power says, "but if we look back further, to centuries and millenia, we have have seen this perturbation before."

Consdier satellite data. Today, researchers can look at information gathered by satellites to see where fires are, how big they are, and even how hot they get. But researchers only have satellite data on wildfires going back to the 1980s. If scientists only used satellite data to compare fires, then they might miss some of the bigger picture patterns.

To find even older information, researchers often turn to the forests themselves. Trees that survive wildfires sometimes have burn scars, which allow scientists to identify when a fire occurred and how severe it was. "The fire burns along, scars the tree, the tree heals, and later when you study this tree, you take a slice of that and determine what years the fire came through," Power says. To go back even further, researchers can look at charcoal and other wildfire clues in lake cores. These tubes of sediment may contain products of wildfires from hundreds to thousands of years back.

Each approach has its own advantages and constraints. Burn scars might record wildfires from decades or even hundreds of years ago, Power notes, but burn scars will only be found on trees that managed to survive and were not obliterated by the blazes. And lake sediment isn't quite as high-resolution as a satellite readout. That's why data from different sources is important to take into account. Various approaches need to be identified and considered together to understand the pattern of western wildfires. "How unprecedented these megafires are depends on which data we're using," Power says.

So far, determining whether or not our 2020 fires were unusual depends on what researchers can find out about the past. "We don't have a perfect answer for the big fires we're seeing right now," Power says. Still, it's apparent that human activities and decisions have a role to play. In addition to forest changes stemming from climate change - such as a proliferation of tree-killing beetles - the way we think about wildfires has also created the current situation. Agencies charged with overseeing America's forests have often treated trees as crops that should not be burned, with wildfires seen as an enemy. But fire is a natural and important part of forests. Prevening burns can lead to a buildup of fuel that then burns more intensely and can spread into habitats that are not as well-adapted to copinig with fires. The great Yellowstone fires of 1988 are an example of what can happen when a no-burn mindset meets the reality of nature.

Studying the history of fires, and what we might be able to learn from them, is part of being able to read the landscape. "I tend to think of landscapes as inherited legacies, and my job is to figure out the process of whatever species are there," Power says. The more we're able to read signs of phenomena like fire, the better we can understand why a patch of forest or grassland looks the way it does today. The CSI aspect of determining what happened and why, Power says, is an empowering demonstration of curiosity, a view that helps us better understand our world and how we relate to it.

Read the latest science news from NHMU.

Riley Black is the author of Skeleton Keys, My Beloved Brontosaurus, Prehistoric Predators, and a science writer for the Natural History Museum of Utah, a part of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. Our mission is to illuminate the natural world and the place of humans within it. In addition to housing outstanding exhibits for the public, NHMU is a research museum. Learn more.