NHMU50: Saving an Allosaurus Graveyard

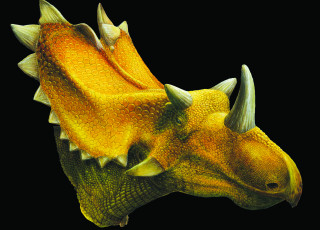

A close-up of Allosaurus fragilis in the Past Worlds gallery exhibit on Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry. Credit: Riley Black

By Riley Black

The third floor fossil collections of the Natural History Museum of Utah holds of the greatest accumulations of dinosaurs in the world. There are thousands upon thousands of specimens, with a significant fraction representing animals seen nowhere else in the world. But a huge chunk of what the Museum’s Paleontology team cares for is the fossils from the Jurassic Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry. There is no greater collection of Allosaurus bones anywhere. But how did the collection come to the museum?

The Cleveland-Lloyd bones have a long history, stretching back over a hundred years. Multiple excavations yielded over 15,000 specimens from this one place, and they were a major research focus of Utah’s first state paleontologist Jim Madsen, Jr. But in 1978, the fate of the collection was in question. “Nobody knew where it was going to go,” remembers former museum curator Frank DeCourten. He would soon find himself helping to decide the fate of the bones.

In that year, while on sabbatical from California State University, DeCourten heard that the University of Utah was looking for an earth sciences professor. He soon got the job, with the disposition of the Cleveland-Lloyd fossils being the first order of business. No one could quite agree on where the bones should go. There were murmurings that the bones might go to Brigham Young University, or perhaps should be given to Utah’s Division of State History. But in forming a close relationship to the Utah Museum of Natural History, DeCourten and others arranged for the Cleveland-Lloyd fossils to become part of our institution as the backbone of a new paleontology collection.

Finding a space for so many bones – including dinosaur hip bones weighing hundreds of pounds and leg bones as tall as an adult person – was a challenge. “When the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Collection came to the museum, the only place we could put it was in the basement,” DeCourten says. That became his base of operations as he became more involved in the collection, in addition to teaching duties at the University. And researchers came from all over to examine the bones. “They were like kids in a toyshop when they came through the Cleveland-Lloyd Collection,” DeCourten says.

Moved to the new Museum building through the backbreaking labor of staff, volunteers, and professional movers, the Cleveland-Lloyd bones still attract researchers from all over the world. “If anything, being there during the time that we were able to bring the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Collection back to campus was the first cornerstone for what is now a very vibrant program in paleontology,” DeCourten says.” The Jurassic bones are hardly the only amazing fossils in the collection, but they helped to put our nascent museum on the map. And they remain part of a legacy that connects the Museum to our community. “It wasn’t our collection, DeCourten says. “It belonged to the people of Utah, and it had to be in their museum.”

Riley Black is the author of Skeleton Keys, My Beloved Brontosaurus, Prehistoric Predators, and a science writer for the Natural History Museum of Utah, a part of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. Our mission is to illuminate the natural world and the place of humans within it. In addition to housing outstanding exhibits for the public, NHMU is a research museum. Learn more.